H. G. Wells

H. G. Wells | |

|---|---|

When the Sleeper Wakes | |

| Spouse | Isabel Mary Wells

(m. 1891; div. 1894)Amy Catherine Robbins

(m. 1895; died 1927) |

| Children | 4, including G. P. and Anthony |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

| |

| Academic background | |

| Academic advisors | Thomas Henry Huxley |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Biology |

| President of PEN International | |

| In office October 1933 – October 1936 | |

| Preceded by | John Galsworthy |

| Succeeded by | Jules Romains |

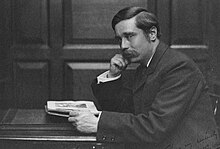

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer. Prolific in many genres, he wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, history, popular science, satire, biography, and autobiography. Wells' science fiction novels are so well regarded that he has been called the "father of science fiction".[1][2]

In addition to his fame as a writer, he was prominent in his lifetime as a forward-looking, even prophetic

Wells rendered his works convincing by instilling commonplace detail alongside a single extraordinary assumption per work – dubbed "Wells's law" – leading

Wells's earliest specialised training was in

Life

Early life

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in

A defining incident of young Wells's life was an accident in 1874 that left him bedridden with a broken leg.[16] To pass the time he began to read books from the local library, brought to him by his father. He soon became devoted to the other worlds and lives to which books gave him access; they also stimulated his desire to write. Later that year he entered Thomas Morley's Commercial Academy, a private school founded in 1849, following the bankruptcy of Morley's earlier school. The teaching was erratic, and the curriculum mostly focused, Wells later said, on producing copperplate handwriting and doing the sort of sums useful to tradesmen. Wells continued at Morley's Academy until 1880. In 1877, his father, Joseph Wells, fractured his thigh. The accident effectively put an end to Joseph's career as a cricketer, and his subsequent earnings as a shopkeeper were not enough to compensate for the loss of the primary source of family income.[18]

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations.[20] From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at Hide's Drapery Emporium in Southsea.[21] His experiences at Hide's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices,[15] later inspired his novels The Wheels of Chance, The History of Mr Polly, and Kipps, which portray the life of a draper's apprentice as well as providing a critique of society's distribution of wealth.[22]: 2

Wells's parents had a turbulent marriage, owing primarily to his mother being a

Teacher

In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at Wookey in Somerset as a pupil–teacher, a senior pupil who acted as a teacher of younger children.[21] In December that year, however, Williams was dismissed for irregularities in his qualifications and Wells was returned to Uppark. After a short apprenticeship at a chemist in nearby Midhurst and an even shorter stay as a boarder at Midhurst Grammar School, he signed his apprenticeship papers at Hyde's. In 1883, Wells persuaded his parents to release him from the apprenticeship, taking an opportunity offered by Midhurst Grammar School again to become a pupil–teacher; his proficiency in Latin and science during his earlier short stay had been remembered.[17][21]

The years he spent in Southsea had been the most miserable of his life to that point, but his good fortune in securing a position at Midhurst Grammar School meant that Wells could continue his self-education in earnest.

He soon entered the Debating Society of the school. These years mark the beginning of his interest in a possible reformation of society. At first approaching the subject through Plato's Republic, he soon turned to contemporary ideas of socialism as expressed by the recently formed Fabian Society and free lectures delivered at Kelmscott House, the home of William Morris. He was also among the founders of The Science School Journal, a school magazine that allowed him to express his views on literature and society, as well as trying his hand at fiction; a precursor to his novel The Time Machine was published in the journal under the title The Chronic Argonauts. The school year 1886–87 was the last year of his studies.[22]: 164

During 1888, Wells stayed in

After teaching for some time—he was briefly on the staff of

Upon leaving the Normal School of Science, Wells was left without a source of income. His aunt Mary—his father's sister-in-law—invited him to stay with her for a while, which solved his immediate problem of accommodation. During his stay at his aunt's, he grew increasingly interested in her daughter, Isabel, whom he later courted. To earn money, he began writing short humorous articles for journals such as The Pall Mall Gazette, later collecting these in Select Conversations with an Uncle (1895) and Certain Personal Matters (1897). So prolific did Wells become at this mode of journalism that many of his early pieces remain unidentified. According to David C. Smith, "Most of Wells's occasional pieces have not been collected, and many have not even been identified as his. Wells did not automatically receive the byline his reputation demanded until after 1896 or so . ... As a result, many of his early pieces are unknown. It is obvious that many early Wells items have been lost."[32] His success with these shorter pieces encouraged him to write book-length work, and he published his first novel, The Time Machine, in 1895.[33]

Personal life

In 1891, Wells

In late summer 1896, Wells and Jane moved to a larger house in Worcester Park, near Kingston upon Thames, for two years; this lasted until his poor health took them to Sandgate, near Folkestone, where he constructed a large family home, Spade House, in 1901. He had two sons with Jane: George Philip (known as "Gip"; 1901–1985) and Frank Richard (1903–1982)[6]: 295 (grandfather of film director Simon Wells). Jane died on 6 October 1927, in Dunmow, at the age of 55, which left Wells devastated. She was cremated at Golders Green, with friends of the couple present including George Bernard Shaw.[27]: 64

Wells had multiple love affairs.[38] Dorothy Richardson was a friend with whom he had a brief affair which led to a pregnancy and miscarriage, in 1907. Wells' wife had been a schoolmate of Richardson.[39] In December 1909, he had a daughter, Anna-Jane, with the writer Amber Reeves,[40] whose parents, William and Maud Pember Reeves, he had met through the Fabian Society. Amber had married the barrister G. R. Blanco White in July of that year, as co-arranged by Wells. After Beatrice Webb voiced disapproval of Wells's "sordid intrigue" with Amber, he responded by lampooning Beatrice Webb and her husband Sidney Webb in his 1911 novel The New Machiavelli as 'Altiora and Oscar Bailey', a pair of short-sighted, bourgeois manipulators. Between 1910 and 1913, novelist Elizabeth von Arnim was one of his mistresses.[41] In 1914, he had a son, Anthony West (1914–1987), by the novelist and feminist Rebecca West, 26 years his junior.[42] In 1920–21, and intermittently until his death, he had a love affair with the American birth control activist Margaret Sanger.[43]

Between 1924 and 1933 he partnered with the 22-year-younger Dutch adventurer and writer Odette Keun, with whom he lived in Lou Pidou, a house they built together in Grasse, France. Wells dedicated his longest book to her (The World of William Clissold, 1926).[44] When visiting Maxim Gorky in Russia 1920, he had slept with Gorky's mistress Moura Budberg,[45] then still Countess Benckendorf and 27 years his junior. In 1933, when she left Gorky and emigrated to London, their relationship renewed and she cared for him through his final illness. Wells repeatedly asked her to marry him, but Budberg strongly rejected his proposals.[46][47]

In Experiment in Autobiography (1934), Wells wrote: "I was never a great amorist, though I have loved several people very deeply".[48] David Lodge's novel A Man of Parts (2011) – a 'narrative based on factual sources' (author's note) – gives a convincing and generally sympathetic account of Wells's relations with the women mentioned above, and others.[49]

Director Simon Wells (born 1961), the author's great-grandson, was a consultant on the future scenes in Back to the Future Part II (1989).[50]

Artist

One of the ways that Wells expressed himself was through his drawings and sketches. One common location for these was the endpapers and title pages of his own diaries, and they covered a wide variety of topics, from political commentary to his feelings toward his literary contemporaries and his current romantic interests. During his marriage to Amy Catherine, whom he nicknamed Jane, he drew a considerable number of pictures, many of them being overt comments on their marriage. During this period, he called these pictures "picshuas".[51] These picshuas have been the topic of study by Wells scholars for many years, and in 2006, a book was published on the subject.[52]

Writer

Some of his early novels, called "

According to

As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real. Touches of prosaic detail are imperative and a rigorous adherence to the hypothesis. Any extra fantasy outside the cardinal assumption immediately gives a touch of irresponsible silliness to the invention.[57][58]

Dr. Griffin / The Invisible Man is a brilliant research scientist who discovers a method of invisibility, but finds himself unable to reverse the process. An enthusiast of random and irresponsible violence, Griffin has become an iconic character in horror fiction.[59] The Island of Doctor Moreau sees a shipwrecked man left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, a mad scientist who creates human-like hybrid beings from animals via vivisection.[60] The earliest depiction of uplift, the novel deals with a number of philosophical themes, including pain and cruelty, moral responsibility, human identity, and human interference with nature.[61] In The First Men in the Moon Wells used the idea of radio communication between astronomical objects, a plot point inspired by Nikola Tesla's claim that he had received radio signals from Mars.[62] In addition to science fiction, Wells produced work dealing with mythological beings like an angel in The Wonderful Visit (1895) and a mermaid in The Sea Lady (1902).[63]

Though Tono-Bungay is not a science-fiction novel, radioactive decay plays a small but consequential role in it. Radioactive decay plays a much larger role in

Wells also wrote non-fiction. His first non-fiction bestseller was Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought (1901). When originally serialised in a magazine it was subtitled "An Experiment in Prophecy", and is considered his most explicitly futuristic work. It offered the immediate political message of the privileged sections of society continuing to bar capable men from other classes from advancement until war would force a need to employ those most able, rather than the traditional upper classes, as leaders. Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of populations from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that "my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea").[67][68]

His bestselling two-volume work,

From quite early in Wells's career, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels.[3] The first of these was A Modern Utopia (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all";[74] two travellers from our world fall into its alternate history. The others usually begin with the world rushing to catastrophe, until people realise a better way of living: whether by mysterious gases from a comet causing people to behave rationally and abandoning a European war (In the Days of the Comet (1906)), or a world council of scientists taking over, as in The Shape of Things to Come (1933, which he later adapted for the 1936 Alexander Korda film, Things to Come). This depicted, all too accurately, the impending World War, with cities being destroyed by aerial bombs. He also portrayed the rise of fascist dictators in The Autocracy of Mr Parham (1930) and The Holy Terror (1939). Men Like Gods (1923) is also a utopian novel. Wells in this period was regarded as an enormously influential figure; the literary critic Malcolm Cowley stated: "by the time he was forty, his influence was wider than any other living English writer".[75]

Wells contemplates the ideas of

Wells also wrote the preface for the first edition of W. N. P. Barbellion's diaries, The Journal of a Disappointed Man, published in 1919. Since "Barbellion" was the real author's pen name, many reviewers believed Wells to have been the true author of the Journal; Wells always denied this, despite being full of praise for the diaries.[78]

In 1927, a Canadian teacher and writer Florence Deeks unsuccessfully sued Wells for infringement of copyright and breach of trust, claiming that much of The Outline of History had been plagiarised from her unpublished manuscript,[79] The Web of the World's Romance, which had spent nearly nine months in the hands of Wells's Canadian publisher, Macmillan Canada.[80] However, it was sworn on oath at the trial that the manuscript remained in Toronto in the safekeeping of Macmillan, and that Wells did not even know it existed, let alone seen it.[81] The court found no proof of copying, and decided the similarities were due to the fact that the books had similar nature and both writers had access to the same sources.[82] In 2000, A. B. McKillop, a professor of history at Carleton University, produced a book on the case, The Spinster & The Prophet: Florence Deeks, H. G. Wells, and the Mystery of the Purloined Past.[83] According to McKillop, the lawsuit was unsuccessful due to the prejudice against a woman suing a well-known and famous male author, and he paints a detailed story based on the circumstantial evidence of the case.[84] In 2004, Denis N. Magnusson, professor emeritus of the Faculty of Law, Queen's University, Ontario, published an article on Deeks v. Wells. This re-examines the case in relation to McKillop's book. While having some sympathy for Deeks, he argues that she had a weak case that was not well presented, and though she may have met with sexism from her lawyers, she received a fair trial, adding that the law applied is essentially the same law that would be applied to a similar case today (i.e., 2004).[85]

In 1933, Wells predicted in The Shape of Things to Come that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940,

In 1938, he published a collection of essays on the future organisation of knowledge and education, World Brain, including the essay "The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia".[88]

Prior to 1933, Wells's books were widely read in Germany and Austria, and most of his science fiction works had been translated shortly after publication.[89] By 1933, he had attracted the attention of German officials because of his criticism of the political situation in Germany, and on 10 May 1933, Wells's books were burned by the Nazi youth in Berlin's Opernplatz, and his works were banned from libraries and book stores.[89] Wells, as president of PEN International (Poets, Essayists, Novelists), angered the Nazis by overseeing the expulsion of the German PEN club from the international body in 1934 following the German PEN's refusal to admit non-Aryan writers to its membership. At a PEN conference in Ragusa, Wells refused to yield to Nazi sympathisers who demanded that the exiled author Ernst Toller be prevented from speaking.[89] Near the end of World War II, Allied forces discovered that the SS had compiled lists of people slated for immediate arrest during the invasion of Britain in the abandoned Operation Sea Lion, with Wells included in the alphabetical list of "The Black Book".[90]

Wartime works

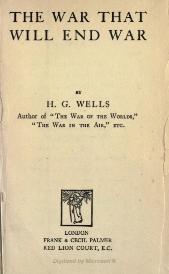

Seeking a more structured way to play war games, Wells wrote

During August 1914, immediately after the outbreak of the First World War, Wells published a number of articles in London newspapers that subsequently appeared as a book entitled The War That Will End War.[6]: 147 [92] He coined the expression with the idealistic belief that the result of the war would make a future conflict impossible.[93] Wells blamed the Central Powers for the coming of the war and argued that only the defeat of German militarism could bring about an end to war.[94] Wells used the shorter form of the phrase, "the war to end war", in In the Fourth Year (1918), in which he noted that the phrase "got into circulation" in the second half of 1914.[95] In fact, it had become one of the most common catchphrases of the war.[94]

In 1918 Wells worked for the British

Travels to Russia and the Soviet Union

Wells visited Russia three times: 1914, 1920 and 1934. After his visits to Petrograd and Moscow, in January 1914, he came back to England, "a staunch Russophile". His views were recorded in a newspaper article, "Russia and England: A Study on Contrasts", published in The Daily News on 1 February 1941, and in his novel Joan and Peter (1918).[97] During his second visit, he saw his old friend Maxim Gorky and with Gorky's help, met Vladimir Lenin. In his book Russia in the Shadows, Wells portrayed Russia as recovering from a total social collapse, "the completest that has ever happened to any modern social organisation."[98] On 23 July 1934, after visiting U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Wells went to the Soviet Union and interviewed Joseph Stalin for three hours for the New Statesman magazine, which was extremely rare at that time. He told Stalin how he had seen 'the happy faces of healthy people' in contrast with his previous visit to Moscow in 1920.[99] However, he also criticised the lawlessness, class discrimination, state violence, and absence of free expression. Stalin enjoyed the conversation and replied accordingly. As the chairman of the London-based PEN International, which protected the rights of authors to write without being intimidated, Wells hoped by his trip to USSR, he could win Stalin over by force of argument. Before he left, he realised that no reform was to happen in the near future.[100][101]

Final years

Wells's greatest literary output occurred before the First World War, which was lamented by younger authors whom he had influenced. In this connection, George Orwell described Wells as "too sane to understand the modern world", and "since 1920 he has squandered his talents in slaying paper dragons."[102] G. K. Chesterton quipped: "Mr Wells is a born storyteller who has sold his birthright for a pot of message".[103]

Wells had

On 28 October 1940, on the radio station

Death

Wells died on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, overlooking Regent's Park, London.[107][16] In his preface to the 1941 edition of The War in the Air, Wells had stated that his epitaph should be: "I told you so. You damned fools".[108] Wells's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 16 August 1946; his ashes were subsequently scattered into the English Channel at Old Harry Rocks, the most eastern point of the Jurassic Coast and about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from Swanage in Dorset.[109]

A commemorative blue plaque in his honour was installed by the Greater London Council at his home in Regent's Park in 1966.[110]

Futurist

A futurist and "visionary", Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and something resembling the World Wide Web.[5] Asserting that "Wells's visions of the future remain unsurpassed", John Higgs, author of Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century, states that in the late 19th century Wells "saw the coming century clearer than anyone else. He anticipated wars in the air, the sexual revolution, motorised transport causing the growth of suburbs and a proto-Wikipedia he called the "world brain". In his novel The World Set Free, he imagined an "atomic bomb" of terrifying power that would be dropped from aeroplanes. This was an extraordinary insight for an author writing in 1913, and it made a deep impression on Winston Churchill."[111]

Many readers have hailed H. G. Wells and George Orwell as special kinds of writers, ones endowed with remarkable prescriptive and prophetic powers. Wells was the twentieth-century prototype of this literary vatic figure: he invented the role, explored its possibilities, especially through new forms of prose and new ways to publish, and defined its boundaries. His impact on his culture was profound; as George Orwell wrote, "The minds of all of us, and therefore the physical world, would be perceptibly different if Wells had never existed."

— The Author as Cultural Hero: H. G. Wells and George Orwell.[112]

In 2011, Wells was among a group of science fiction writers featured in the Prophets of Science Fiction series, a show produced and hosted by film director Sir Ridley Scott, which depicts how predictions influenced the development of scientific advancements by inspiring many readers to assist in transforming those futuristic visions into everyday reality.[113] In a 2013 review of The Time Machine for the New Yorker magazine, Brad Leithauser writes, "At the base of Wells's great visionary exploit is this rational, ultimately scientific attempt to tease out the potential future consequences of present conditions—not as they might arise in a few years, or even decades, but millennia hence, epochs hence. He is world literature's Great Extrapolator. Like no other fiction writer before him, he embraced "deep time".[114]

Political views

Wells was a

Winston Churchill was an avid reader of Wells's books, and after they first met in 1902 they kept in touch until Wells died in 1946.[115] As a junior minister Churchill borrowed lines from Wells for one of his most famous early landmark speeches in 1906, and as Prime Minister the phrase "the gathering storm"—used by Churchill to describe the rise of Nazi Germany—had been written by Wells in The War of the Worlds, which depicts an attack on Britain by Martians.[115] Wells's extensive writings on equality and human rights, most notably his most influential work, The Rights of Man (1940), laid the groundwork for the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations shortly after his death.[119]

His efforts regarding the League of Nations, on which he collaborated on the project with Leonard Woolf with the booklets The Idea of a League of Nations, Prolegomena to the Study of World Organization, and The Way of the League of Nations, became a disappointment as the organization turned out to be a weak one unable to prevent the Second World War, which itself occurred towards the very end of his life and only increased the pessimistic side of his nature.[120] In his last book Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945), he considered the idea that humanity being replaced by another species might not be a bad idea. He referred to the era between the two World Wars as "The Age of Frustration".[121]

Wells was initially an opponent of

He was a member of The Other Club, a London dining club.

Religious views

Wells' views on God and religion changed over his lifetime. Early in his life he distanced himself from Christianity, and later from

In God the Invisible King (1917), Wells wrote that his idea of God did not draw upon the traditional religions of the world:

This book sets out as forcibly and exactly as possible the religious belief of the writer. [Which] is a profound belief in a personal and intimate God. ... Putting the leading idea of this book very roughly, these two antagonistic typical conceptions of God may be best contrasted by speaking of one of them as God-as-Nature or the Creator, and of the other as God-as-Christ or the Redeemer. One is the great Outward God; the other is the Inmost God. The first idea was perhaps developed most highly and completely in the God of Spinoza. It is a conception of God tending to pantheism, to an idea of a comprehensive God as ruling with justice rather than affection, to a conception of aloofness and awestriking worshipfulness. The second idea, which is contradictory to this idea of an absolute God, is the God of the human heart. The writer suggested that the great outline of the theological struggles of that phase of civilisation and world unity which produced Christianity, was a persistent but unsuccessful attempt to get these two different ideas of God into one focus.[124]

Later in the work, he aligns himself with a "renascent or modern religion ... neither atheist nor Buddhist nor Mohammedan nor Christian ... [that] he has found growing up in himself".[125]

Of

Wells's opposition to organised religion reached a fever pitch in 1943 with publication of his book

Literary influence and legacy

The science fiction historian John Clute describes Wells as "the most important writer the genre has yet seen", and notes his work has been central to both British and American science fiction.[129] Science fiction author and critic Algis Budrys said Wells "remains the outstanding expositor of both the hope, and the despair, which are embodied in the technology and which are the major facts of life in our world".[130] He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921, 1932, 1935, and 1946.[10] Wells so influenced real exploration of space that impact craters on Mars and the Moon were named after him:[131]

Wells's genius was his ability to create a stream of brand new, wholly original stories out of thin air. Originality was Wells's calling card. In a six-year stretch from 1895 to 1901, he produced a stream of what he called "scientific romance" novels, which included The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds and The First Men in the Moon. This was a dazzling display of new thought, endlessly copied since. A book like The War of the Worlds inspired every one of the thousands of alien invasion stories that followed. It burned its way into the psyche of mankind and changed us all forever.

— Cultural historian John Higgs, The Guardian.[111]

In the United Kingdom, Wells's work was a key model for the British "scientific romance", and other writers in that mode, such as

In the United States, Hugo Gernsback reprinted most of Wells's work in the pulp magazine Amazing Stories, regarding Wells's work as "texts of central importance to the self-conscious new genre".[129] Later American writers such as Ray Bradbury,[142] Isaac Asimov,[143] Frank Herbert,[144] Carl Sagan,[131] and Ursula K. Le Guin[145] all recalled being influenced by Wells.

Sinclair Lewis's early novels were strongly influenced by Wells's realistic social novels, such as The History of Mr Polly; Lewis also named his first son Wells after the author.[146] Lewis nominated H. G. Wells for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1932.[10]

In an interview with The Paris Review, Vladimir Nabokov described Wells as his favourite writer when he was a boy and "a great artist."[147] He went on to cite The Passionate Friends, Ann Veronica, The Time Machine, and The Country of the Blind as superior to anything else written by Wells's British contemporaries. Nabokov said: "His sociological cogitations can be safely ignored, of course, but his romances and fantasies are superb."[147]

Jorge Luis Borges wrote many short pieces on Wells in which he demonstrates a deep familiarity with much of Wells's work.[148] While Borges wrote several critical reviews, including a mostly negative review of Wells's film Things to Come,[149] he regularly treated Wells as a canonical figure of fantastic literature. Late in his life, Borges included The Invisible Man and The Time Machine in his Prologue to a Personal Library,[150] a curated list of 100 great works of literature that he undertook at the behest of the Argentine publishing house Emecé. Canadian author Margaret Atwood read Wells's books,[77] and he also inspired writers of European speculative fiction such as Karel Čapek[145] and Yevgeny Zamyatin.[145]

In 2021, Wells was one of six British writers commemorated on a

Representations

Literary

- The superhuman protagonist of J. D. Beresford's 1911 novel, The Hampdenshire Wonder, Victor Stott, was based on Wells.[133]

- In Rotary Club in 1933 as "my friend Mr. Wells".[152]

- In C. S. Lewis's novel That Hideous Strength (1945), the character Jules is a caricature of Wells,[153] and much of Lewis's science fiction was written both under the influence of Wells and as an antithesis to his work (or, as he put it, an "exorcism"[154] of the influence it had on him).

- In Brian Aldiss's novella The Saliva Tree (1966), Wells has a small off-screen guest role.[155]

- In Saul Bellow's novel Mr. Sammler's Planet (1970), Wells is one of several historical figures the protagonist met when he was a young man.[156]

- In The Dancers at the End of Time by Michael Moorcock (1976) Wells has an important part.

- In The Map of Time (2008) by Spanish author Félix J. Palma; Wells is one of several historical characters.[157]

- Wells is one of the two Georges in Paul Levinson's 2013 time-travel novelette, "Ian, George, and George", published in Analog magazine.[158]

- David Lodge's novel A Man of Parts (2011) is a literary retelling of the life of Wells.

Dramatic

- Rod Taylor portrays Wells[159][160] in the 1960 science fiction film The Time Machine (based on the novel of the same name), in which Wells uses his time machine to try to find his Utopian society.[160]

- Malcolm McDowell portrays Wells in the 1979 science fiction film Time After Time, in which Wells uses a time machine to pursue Jack the Ripper to the present day.[160] In the film, Wells meets "Amy" in the future who then returns to 1893 to become his second wife Amy Catherine Robbins.

- Wells is portrayed in the 1985 story 22nd season of the BBC science-fiction television series Doctor Who. In this story, Herbert, an enthusiastic temporary companion to the Doctor, is revealed to be a young H. G. Wells. The plot is loosely based upon the themes and characters of The Time Machine with references to The War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man and The Island of Doctor Moreau. The story jokingly suggests that Wells's inspiration for his later novels came from his adventure with the Sixth Doctor.[161]

- In the BBC2 anthology series Encounters about imagined meetings between historical figures, Beautiful Lies, by Paul Pender (15 August 1992) centred on an acrimonious dinner party attended by Wells (Richard Todd), George Orwell (Jon Finch), and William Empson (Patrick Ryecart).

- The character of Wells also appeared in several episodes of Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman (1993–1997), usually pitted against the time-travelling villain known as Tempus (Lane Davies). Wells's younger self was played by Terry Kiser, and the older Wells was played by Hamilton Camp.

- In the British TV mini-series The Infinite Worlds of H. G. Wells (2001), several of Wells's short stories are dramatised but are adapted using Wells himself (Tom Ward) as the main protagonist in each story.

- In the Disney Channel Original Series Phil of the Future, which centres on time-travel, the present-day high school that the main characters attend is named "H. G. Wells".[162]

- In the 2006 television docudrama H. G. Wells: War with the World, Wells is played by Michael Sheen.[163]

- Television episode "World's End" of Cold Case (2007) is about how the discovery of human remains in the bottom of a well leads to the reinvestigation of the case of a housewife who went missing during Orson Welles' radio broadcast of "War of the Worlds".[164]

- On the science fiction television series Warehouse 13 (2009–2014), there is a female version Helena G. Wells. When she appeared, she explained that her brother was her front for her writing because a female science fiction author would not be accepted.[165]

- Comedian Paul F. Tompkins portrays a fictional Wells as the host of The Dead Authors Podcast, wherein Wells uses his time machine to bring dead authors (played by other comedians) to the present and interview them.[166][167]

- H. G. Wells as a young boy appears in the Legends of Tomorrow episode "The Magnificent Eight". In this story, the boy Wells is dying of consumption but is cured by a time-travelling Martin Stein.

- In the four-part series The Nightmare Worlds of H. G. Wells (2016), Wells is played by Ray Winstone.[168]

- In the 2017 television series version of Time After Time, based on the 1979 film, H. G. Wells is portrayed by Freddie Stroma.[169]

- In the 2019 television adaptation of The War of the Worlds, the character of 'George', played by Rafe Spall, demonstrates a number of elements of Wells's own life, including his estrangement from his wife and unmarried co-habitation with the character of 'Amy'.[170]

- Wells is played by Nick Cave in the 2021 film The Electrical Life of Louis Wain.[171]

Film adaptations

The novels and short stories of H. G. Wells have been adapted for cinema. These include Island of Lost Souls (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), Things to Come (1936), The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1937), The War of the Worlds (1953), The Time Machine (1960), First Men in the Moon (1964), The Island of Dr. Moreau (1977), Time After Time (1979), The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996), The Time Machine (2002) and War of the Worlds (2005).[172][173][174][175]

Literary papers

In 1954, the

Bibliography

See also

- Science fiction portal

- Scientific Marvelous

References

- OL 7485895M.

- ^ "H. G. Wells – father of science fiction with hopes and fears for how science will shape our future". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-06-008381-6.

- ^ a b Handwerk, Brian (21 September 2016). "The Many Futuristic Predictions of H.G. Wells That Came True". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ a b James, Simon John (9 October 2017). "HG Wells: A visionary who should be remembered for his social predictions, not just his scientific ones". The Independent.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8195-6725-3. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-14-143997-6.

- ^ "How Hollywood fell for a British visionary". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ Longmans, Green. p. 99.

- ^ a b c "Nomination archive". Nobel Foundation. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Philmus, Robert M.; Hughes, David Y., eds. (1975). H. G. Wells: Early Writings in Science and Science Fiction. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. p. 179.

- ^ "H. G. Wells' politics". British Library. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "H. G. Wells". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ "H. G. Wells – Author, Historian, Teacher with Type 2 Diabetes". www.diabetes.co.uk. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ OL 7359945M.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 0-300-03672-8

- ^ "Sep. 21, 1866: Wells Springs Forth". Wired. 9 October 2017.

- ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

- ^ "HG Wells: prophet of free love". The Guardian. 11 October 2017.

- ^ OCLC 458934085.

- ^ OL 2854973M.

- ^ a b Pilkington, Ace G. (2017). Science Fiction and Futurism: Their Terms and Ideas. McFarland. p. 137.

- ^ Ball, Philip (18 July 2018). "What the War of the Worlds means now". New Statesman. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ISBN 0-8240-0119-2. Some of the text is available online.

- ^ Brome, Vincent (2008). H. G. Wells. House of Stratus. p. 180.

- ^ OL 3770014M.

- ^ Bowman, Jamie (3 October 2016). "Teaching spell near Wrexham inspired one of the nation's greatest science fiction writers". The Leader. Wrexham. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "Hampstead: Education". A History of the County of Middlesex. 9: 159–169. 1989. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "A. A. Milne". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ISBN 9780945636052.

- ISBN 978-0-300-03672-5.

- Praeger. p. 50.

- ^ "H. G. Wells and Woking". Celebrate Woking. Woking Borough Council. 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

H. G. Wells arrived in Woking in May 1895. He lived at 'Lynton', Maybury Road, Woking, which is now numbered 141 Maybury Road. Today, there is an English Heritage blue plaque displayed on the front wall of the property, which marks his period of residence.

- ^ "They Did What? 15 Famous People Who Actually Married Their Cousins". Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Woking, Surrey: Woking Borough Council. 2016. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ Before the 143rd anniversary of Wells's birth, Google published a cartoon riddle series with the solution being the coordinates of Woking's nearby Horsell Common—the location of the Martian landings in The War Of The Worlds—described in newspaper article by Schofield, Jack (21 September 2009). "H. G. Wells – Google reveals answer to teaser doodles". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-8133-3394-6.

- ISBN 978-0-252006-31-9.

- ^ Margaret Drabble (1 April 2005). "A room of her own". The Guardian.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35883. Retrieved 29 December 2022. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "H. G. Wells". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015.

- ^ "The Passionate Friends: H. G. Wells and Margaret Sanger", at the Margaret Sanger Paper Project.

- ^ Dixon, Kevin (20 July 2014). "Odette Keun, H. G. Wells and the Third Way". People's Republic of South Devon. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Aron, Nina Renata (18 May 2017). "The impossibly glamorous life of this Russian baroness spy needs to be a movie". Medium. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Wells, H.G. (1934). H.G. Wells: Experiment in Autobiography. New York City: J. B. Lippincott & Co.

- ^ Lodge, David (2011). A Man of Parts. Random House.

- ^ "Simon Wells". British Film Institute. 22 October 2017. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017.

- ^ "H. G. Wells' cartoons, a window on his second marriage, focus of new book | Archives | News Bureau". University of Illinois. 31 May 2006. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ISBN 0-252-03045-1(cloth: acid-free paper).

- S2CID 23027055.

- ^ "The Man Who Invented Tomorrow". Archived from the original on 5 August 2012.

In 1902, when Arnold Bennett was writing a long article for Cosmopolitan about Wells as a serious writer, Wells expressed his hope that Bennett would stress his "new system of ideas". Wells developed a theory to justify the way he wrote (he was fond of theories), and these theories helped others write in similar ways.

- ^ "A brief history of time travel". The Independent. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

Time travel began 100 years ago, with the publication of H. G. Wells' The Time Machine in January 1895. The notion of moving freely backwards and forwards in time, in the same way that we can move about in space, that was something new.

- ^ "The Time Machine – Scientists and Gentlemen – WriteWork". www.writework.com.

- ISBN 978-81-269-1036-6.

- OCLC 948822249.

- ^ The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination. McFarland. 2009. pp. 41–42.

- ^ "Novels: The Island of Doctor Moreau". Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Barnes & Noble. "The Island of Doctor Moreau: Original and Unabridged". Barnes & Noble.

- ^ Brewer, Nathan (19 October 2020). "Your Engineering Heritage: Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla as Science Fiction Characters". IEEE-USA InSight. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Sherbourne, Michael (2010). H. G. Wells: Another Kind of Life. Peter Owen. p. 108.

- ^ a b c "H. G. Wells and the Scientific Imagination". The Virginia Quarterly Review. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8032-9820-0.

- OL 7721091M.

- ^ "Annual H. G. Wells Award for Outstanding Contributions to Transhumanism". 20 May 2009. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-521-37257-2.

- ^ "The Outline of History—H. G. Wells". 20 April 2003. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1994). "Education and World Peace, A Message to the Progressive Education Association, 23 November 1934". Ideas and Opinions: With An Introduction by Alan Lightman, Based on Mein Weltbild, edited by Carl Seelig, and Other Sources, New Translations and Revisions by Sonja Bargmann. New York: The Modern Library. p. 63.

- ^ H. G. Wells, The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (London: William Heinemann, 1932), p. 812.

- ^ "Wells, H. G. 1922. A Short History of the World". Bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Wells, H. G. (2006). A Short History of the World. Penguin UK.

- OL 52256W.

- ^ Cowley, Malcolm. "Outline of Wells's History". The New Republic Vol. 81 Issue 1041, 14 November 1934 (pp. 22–23).

- ISBN 0-8093-1113-5.

- ^ a b Wells, H. G. (2005). The Island of Dr Moreau. "Fear and Trembling". Penguin UK.

- ^ "The Quotable Barbellion – A Barbellion Chronology". Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ At the time of the alleged infringement in 1919–20, unpublished works were protected in Canada under common law.Magnusson, Denis N. (Spring 2004). "Hell Hath No Fury: Copyright Lawyers' Lessons from Deeks v. Wells". Queen's Law Journal. 29: 692, note 39.

- ^ Magnusson, Denis N. (Spring 2004). "Hell Hath No Fury: Copyright Lawyers' Lessons from Deeks v. Wells". Queen's Law Journal. 29: 682.

- ^ Clarke, Arthur C. (March 1978). "Professor Irwin and the Deeks Affair". p. 91. Science Fiction Studies. SF-TH Inc. 5

- ^ "Deeks v. Wells, 1931 CanLII 157 (ONSC (HC Div); ONSC (AppDiv))". CanLII. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ McKillop, A. B. (2000) Macfarlane Walter & Ross, Toronto.

- ^ Deeks, Florence A. (1930s) "Plagiarism?" unpublished typescript, copy in Deeks Fonds, Baldwin Room, Toronto Reference Library, Toronto, Ontario.

- ^ Magnusson, Denis N. (Spring 2004). "Hell Hath No Fury: Copyright Lawyers' Lessons from Deeks v. Wells". Queen's Law Journal. 29: 680, 684.

- ISBN 978-0-14-144104-7.

- ^ Rayward, W. Boyd. (1999). “H.G. Wells’s Idea of a World Brain: A Critical Reassessment.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 50 (7): 557–73.

- ^ "eBooks@Adelaide has now officially closed". University Library | University of Adelaide. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Patrick Parrinder and John S. Partington (2005). The Reception of H. G. in Europe. pp. 106–108. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^ Wells, Frank. H. G. Wells—A Pictorial Biography. London: Jupiter Books, 1977, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Rundle, Michael (9 April 2013). "How H. G. Wells Invented Modern War Games 100 Years Ago". The Huffington Post.

- ^ "A War to End All War". Vision.org. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

Wells wrote: "This is now a war for peace. It aims straight at disarmament. It aims at a settlement that shall stop this sort of thing for ever. Every soldier who fights against Germany now is a crusader against war. This, the greatest of all wars, is not just another war—it is the last war!"

- ^ "Armistice Day: WWI was meant to be the war that ended all wars. It wasn't". Euronews. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-10463-0. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-4375-2652-3. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ a b "1914 Authors' Manifesto Defending Britain's Involvement in WWI, Signed by H. G. Wells and Arthur Conan Doyle". Slate. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- JSTOR j.ctv346p26.9– via JSTOR.

- ^ H. G. Wells, Russia in the Shadows (New York: George H. Doran, 1921), p. 21.

- ^ "H. G. Wells Interviews Joseph Stalin in 1934; Declares "I Am More to The Left Than You, Mr. Stalin"". Open Culture. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Service, Robert (2007). Comrades. London: Macmillan. p. 205.

- ^ "MARXISM VERSUS LIBERALISM". Red Star Press Ltd. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Orwell, George (August 1941). "Wells, Hitler and the World State". Horizon. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-945636-05-2.

- ^ "H. G. Wells—Diabetes UK". 14 April 2008. Archived from the original on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ "Diabetes UK: Our History". Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-9769400-0-5.

- ^ Bradberry, Grace (23 August 1996). "The secret life of H. G. Wells". The Times. No. 65666. London. p. 18.

- ^ "Preface to the 1941 edition of The War in the Air". Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ISBN 0-09-134540-5.

- ^ "H. G. Wells (1866–1946)". Blue Plaques. English Heritage.

- ^ a b Higgs, John (13 August 2016). "H. G. Wells's prescient visions of the future remain unsurpassed". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- JSTOR 24780682.

- ^ Teague, Jason Cranford (9 November 2011). "The Prophets of Science Fiction Explores Sci-Fi's Best Writers". Wired. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Leithauser, Brad (20 October 2013). "H. G. Wells' ghost". New Yorker. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "Churchill 'borrowed' famous lines from books by H. G. Wells". The Independent. 22 October 2017.

- ^ "Churchill borrowed some of his biggest ideas from H. G. Wells". University of Cambridge. 27 November 2006. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ISBN 0-7100-7866-8.

- ^ Foot, Michael. H. G.: History of Mr. Wells. Doubleday, 1985 (ISBN 978-1-887178-04-4), Black Swan, New edition, Oct 1996 (paperback, ISBN 0-552-99530-4) p. 194.

- ISBN 978-1-349-27995-1.

- The Fate of Homo Sapiens, (London: Secker & Warburg, 1939), p 89-90.

- ^ Herbert George Wells Newsletter, Volume 2. p. 10. H. G. Wells Society, 1981

- ^ "H.G. Wells vs. the Jews". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 24 October 2023.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1995), Introduction to H. G. Wells, The Conquest of Time [1941]; New York: Dover Books. This introduction was also published in Gardner's book From the Wandering Jew to William F. Buckley, Jr: On Science, Literature and Religion (2000), Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, pp 235–238.

- OCLC 261326125.

- ^ Wells, H. G. (1917). The cosmology of modern religion.

- OCLC 68958585.

- The Fate of Homo Sapiens, p 291.

- ISBN 0-902291-65-3.

- ^ ISBN 0-7513-0202-3(p. 114–115).

- ^ Budrys, Algis (September 1968). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 187–193.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ISBN 0-203-87470-6(pp. 205–210).

- ^ ISBN 0-8103-9941-5.

- ISBN 1-4344-5743-5(pp. 9–90).

- ISBN 0-8103-1051-1p. 1002.

- ISBN 0-7614-7601-6p. 422.

- ISBN 0-916732-74-6p. 60.

- ^ "John Wyndham (1903-1969)". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ "The George Orwell and H. G. Wells row: Gain and Loss in the Utopian and Dystopian Feud". Goldsmiths, University of London. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- PMID 18578028.

- ^ Haldane, J. B. S. "On Being the Right Size" (PDF).

- Strand Mag. 4 June 2015.

- Garden City, NY: Doubleday. 1979. p. 167.

- ^ "Vertex Magazine Interview". Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2012. with Frank Herbert, by Paul Turner, October 1973, Volume 1, Issue 4.

- ^ a b c John Huntington, "Utopian and Anti-Utopian Logic: H. G. Wells and his Successors". Science Fiction Studies, July 1982.

- ^ "The Romance of Sinclair Lewis". The New York Review of Books. 22 September 2017.

- ^ a b Gold, Herbert. "Vladimir Nabokov, The Art of Fiction No. 40". The Paris Review. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Borges, Jorge Luis. The Total Library. Edited by Eliot Weinberger. London: Penguin Books, 1999. Pp. 150.

- ^ Borges, Jorge Luis. "Wells the Visionary" in The Total Library. Edited by Eliot Weinberger. London: Penguin Books, 1999. Pp. 150.

- ^ "Jorge Luis Borges Selects 74 Books for Your Personal Library | Open Culture". Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Stamps to feature original artworks celebrating classic science fiction novels". Yahoo. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

Royal Mail has released images of original artworks being issued on a new set of stamps to celebrate six classic science fiction novels by British writers.

- ^ A. Reynolds Morse, Shiel in Diverse Hands: A Collection of Essays. Cleveland, OH: Reynolds Morse Foundation, 1983. pp. 109–113.

- ^ Rolfe; Parrinder (1990: 226)

- ^ Lewis, C. S., Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life. New York & London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1955. p. 36.

- ISBN 978-1-59077-357-4.

- ISBN 0-8386-3989-5. p. 40.

- ^ Lenny Picker (4 April 2011). "Victorian Time Travel: PW Talks with Felix J. Palma". Publishersweekly.com. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Paul Levinson, "Ian, George, and George", Analog, December 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-275-98395-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-786-47911-5.

- ^ "Timelash". BBC. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ "'Phil Of The Future' Arch-Enemies Pim And Candida Are Now BFFs". MTV. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "H. G. Wells: War With The World". BBC. 22 October 2017.

- ^ World's End, retrieved 8 October 2019

- ^ "Warehouse 13: About the Series". Syfy. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Hardwick, Robin (21 April 2015). "Best Podcasts of the Week". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Hitfix.

- ^ "Ray Winstone stars as H. G. Wells". The Independent. 22 October 2017.

- ^ Wagmeister, Elizabeth (17 February 2016). "ABC's 'Time After Time' Pilot Casts Josh Bowman, Freddie Stroma as Jack the Ripper & H. G. Wells". Variety. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Filming begins on BBC One drama The War of the Worlds". BBC. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ "Taika Waititi, Nick Cave And Olivia Colman Cameos Revealed For The Electrical Life Of Louis Wain – Exclusive". Empire. 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Greeley Daily Tribune. Greeley, Colorado. 31 October 1933. p. 2. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "The Time Machine – Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Steven Spielberg Goes To War". Empire. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- )

- ^ a b "H. G. Wells papers, 1845–1946 | Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign". Rare Book & Manuscript Library Manuscript Collections Database. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois". Retrieved 29 December 2022.

Further reading

- Bergonzi, Bernard (1961). The Early H. G. Wells: A Study of the Scientific Romances. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-0126-0.

- Cole, Sarah (2021). Inventing Tomorrow: H. G. Wells and the Twentieth Century. Columbia University Press.

- Dickson, Lovat. H. G. Wells: His Turbulent Life & Times. 1969.

- Elber-Aviram, Hadas (2021). "Chapter 2: The Martian on Primrose Hill: Wells's scientific romances". Fairy Tales of London: British Urban Fantasy, 1840 to the Present. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 61–94. ISBN 978-1-350-11069-4.

- Gilmour, David. The Long Recessional: The Imperial Life of Rudyard Kipling. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-374-52896-9).

- Godfrey, Emelyne, ed. (2016). Utopias and Dystopias in the Fiction of H. G. Wells and William Morris: Landscape and Space. Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-137-52340-2.

- Gomme, A. W., Mr. Wells as Historian. Glasgow: MacLehose, Jackson, and Co., 1921.

- Gosling, John. Waging the War of the Worlds. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 2009 (paperback, ISBN 0-7864-4105-4).

- James, Simon J. (2012). Maps of Utopia: H. G. Wells, Modernity, and the End of Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960659-7.

- Jasanoff, Maya, "The Future Was His" (review of Sarah Cole, Inventing Tomorrow: H. G. Wells and the Twentieth Century, Columbia University Press, 374 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVII, no. 12 (23 July 2020), pp. 50–51. Writes Jasanoff (p. 51): "Although [Wells] was prophetically right, and right-minded, about some things ... [n]owhere was he more disturbingly wrong than in his loathsome affinity for eugenics ...."

- Lynn, Andrea The secret love life of H. G. Wells

- Mackenzie, Norman and Jean, The Time Traveller: the Life of H. G. Wells, London: Weidenfeld, 1973, ISBN 0-2977-6531-0

- Mauthner, Martin. German Writers in French Exile, 1933–1940, London: Vallentine and Mitchell, 2007, ISBN 978-0-85303-540-4.

- McConnell, Frank (1981). The Science Fiction of H.G. Wells. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195028119.

- McLean, Steven. 'The Early Fiction of H. G. Wells: Fantasies of Science'. Palgrave, 2009, ISBN 978-0-230-53562-6.

- Page, Michael R. (2012). The Literary Imagination from Erasmus Darwin to H. G. Wells: Science, Evolution, and Ecology. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-3869-4.

- Parrinder, Patrick (1995). Shadows of the Future: H. G. Wells, Science Fiction and Prophecy. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0332-0.

- Partington, John S. Building Cosmopolis: The Political Thought of H. G. Wells. Ashgate, 2003, ISBN 978-0-7546-3383-9.

- Roberts, Adam. H. G. Wells A Literary Life. Springer International Publishing, 2019, ISBN 978-3-03-026421-5.

- Roukema, Aren. 2021. "The Esoteric Roots of Science Fiction: Edward Bulwer-Lytton, H. G. Wells, and the Occlusion of Magic." Science Fiction Studies 48 (2): 218–42.

- Shadurski, Maxim. The Nationality of Utopia: H. G. Wells, England, and the World State. London: Routledge, 2020, ISBN 978-0-36733-049-1.

External links

- H. G. Wells at IMDb

- H. G. Wells at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- H. G. Wells at the Internet Book List

- H. G. Wells discography at Discogs

- H. G. Wells at Library of Congress, with 772 library catalogue records

- Future Tense – The Story of H. G. Wells at BBC One – 150th anniversary documentary (2016)

- "In the footsteps of H. G. Wells" at New Statesman – "The great author called for a Human Rights Act; 60 years later, we have it" (2000)

Sources—collections

- Works by H. G. Wells in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by H. G. Wells at Project Gutenberg

- Works by H. G. Wells at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about H. G. Wells at Internet Archive

- Works by H. G. Wells at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Free H. G. Wells downloads for iPhone, iPad, Nook, Android, and Kindle in PDF and all popular eBook reader formats (AZW3, EPUB, MOBI) at ebooktakeaway.com

- H. G. Wells at the British Library

- H. G. Wells papers at University of Illinois

- Ebooks by H. G. Wells at Global Grey Ebooks

- Newspaper clippings about H. G. Wells in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Sources—letters, essays and interviews

- Archive of Wells's BBC broadcasts

- Film interview with H. G. Wells Archived 2010-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- "Stephen Crane. From an English Standpoint", by Wells, 1900.

- Rabindranath Tagore: In conversation with H. G. Wells. Rabindranath Tagore and Wells conversing in Geneva in 1930.

- "Introduction", to W. N. P. Barbellion's The Journal of a Disappointed Man, by Wells, 1919.

- "Woman and Primitive Culture", by Wells, 1895.

- Letter, to M. P. Shiel, by Wells, 1937.

Biography

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "H. G. Wells". In Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36831. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- "H. G. Wells biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

Critical essays

- An introduction to The War of the Worlds by Iain Sinclair on the British Library's Discovering Literature website.

- "An Appreciation of H. G. Wells", by Mary Austin, 1911.

- "Socialism and the Family" (1906) by Belfort Bax, Part 1, Part 2.

- "H. G. Wells warned us how it would feel to fight a War of the Worlds", by Niall Ferguson, in The Telegraph, 24 June 2005.

- "H. G. Wells's Idea of a World Brain: A Critical Re-assessment", by W. Boyd Rayward, in Journal of the American Society for Information Science 50 (15 May 1999): 557–579

- "Mr H. G. Wells and the Giants", by G. K. Chesterton, from his book Heretics (1908).

- "The Internet: a world brain?", by Martin Gardner, in Skeptical Inquirer, Jan–Feb 1999.

- "Science Fiction: The Shape of Things to Come", by Mark Bould, in The Socialist Review, May 2005.

- "Who needs Utopia? A dialogue with my utopian self (with apologies, and thanks, to H. G. Wells)", by Gregory Claeys in Spaces of Utopia: An Electronic Journal, no 1, Spring 2006.

- "When H. G. Wells Split the Atom: A 1914 Preview of 1945", by Freda Kirchwey, in The Nation, posted 4 September 2003 (original 18 August 1945 issue).

- "War of the Worldviews", by John J. Miller, in The Wall Street Journal Opinion Journal, 21 June 2005.

- "Wells's Autobiography", by John Hart, from New International, Vol.2 No.2, Mar 1935, pp. 75–76.

- "History in the Science Fiction of H. G. Wells", by Patrick Parrinder, Cycnos, 22.2 (2006).

- "From the World Brain to the Worldwide Web", by Martin Campbell-Kelly, Gresham College Lecture, 9 November 2006.

- "The Beginning of Wisdom: On Reading H. G. Wells", by Vivian Gornick, Boston Review, 31.1 (2007).

- John Hammond, The Complete List of Short Stories of H. G. Wells

- "H. G. Wells Predictions Ring True, 143 Years Later" at National Geographic

- "H. G. Wells, the man I knew" Obituary of Wells by George Bernard Shaw, at the New Statesman

- Elber-Aviram, Hadas (2015). ""My own particular city": H. G. Wells's Fantastical London". The Wellsian (38): 97–117.

- Hughes, David Y. (1998). "A Queer Notion of Grant Allen's". JSTOR 4240701.

- Scuriatti, Laura (2003). "A Tale of Two Cities: H. G. Wells's The Door in the Wall". In Partington, John S. (ed.). The Wellsian: Selected Essays on H. G. Wells. Illustrated by Alvin Landon Coburn. OCLC 54814627.