Protoceratopsidae

| Protoceratopsids | |

|---|---|

| |

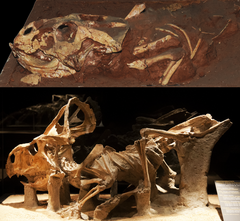

| Two protoceratopsids: Bagaceratops (top) and Protoceratops (bottom) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ceratopsia |

| Parvorder: | † Coronosauria

|

| Family: | †Protoceratopsidae Granger & Gregory, 1923 |

| Type species | |

| † Protoceratops andrewsi Granger & Gregory, 1923

| |

| Subgroups | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Protoceratopsidae is a family of basal (primitive)

Description

Protoceratopsids were relatively small ceratopsians, averaging around 1-2.5 m in length from head to tail.

The vertebral column of protoceratopsids was S-shaped, and the vertebrae had unusually long

Classification

The family Protoceratopsidae was introduced by

Sereno in 2000 included three genera in Protoceratopsidae: Protoceratops,

In 2019 Czepiński analyzed a vast majority of referred specimens to the ceratopsians Bagaceratops and Breviceratops, and concluded that most were in fact specimens of the former. Although the genera Gobiceratops, Lamaceratops, Magnirostris, and Platyceratops, were long considered valid and distinct taxa, and sometimes placed within Protoceratopsidae, Czepiński found the diagnostic features used to distinguish these taxa to be largely present in Bagaceratops and thus becoming synonyms of this genus. Under this reasoning, Protoceratopsidae consists of Bagaceratops, Breviceratops, and Protoceratops. Based on cranial characters such as presence or absence of premaxillary teeth and an antorbital fenestra, P. andrewsi is the basal-most protoceratopsid and Bagaceratops the derived-most one. Below are the proposed phylogenetic relationships within Protoceratopsidae by Czepiński:[13]

| Protoceratopsidae |

| |||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Daily activity

Based on the size of its

Sexual Dimorphism

There is no conclusive evidence supporting sexual dimorphism for Protoceratops andrewsi

Growth

There are three phases in the life cycle of a protoceratopsid: juvenile, subadult, and adult. Juveniles are roughly one third the size of an adult and have an underdeveloped frill and nasal bump. They have not developed epijugals. Nests containing juveniles have been found indicating that they received some level of parental care.[17] In the subadult stage, individuals are two thirds the size of an adult, and the frill and quadrates grow wider. The epijugal begins forming. As an adult, the frill becomes even larger, the epijugal is fully formed, and a small nasal horn develops.[15]

Social behavior

There is evidence that Protoceratops formed groups. Specimens of juveniles and young adults are often found in groups, although adults tend to be solitary. The nature of these groups is not completely known, though herds of young likely formed for protection from predators, and adults are believed to have come together for communal nesting.[18]

Locomotion

Protoceratopsids were likely slow runners and tended to move at a walk or a trot.[1] Their legs may have been straight, creating an upright posture, but there are some theories that they were splayed out to the side, contributing to their slowness.[19] The skeleton of Protoceratops juveniles indicates that protoceratopsids were able to employ facultative bipedalism when young and became obligate quadrupeds in adulthood. However, adults still had proportions allowing the capacity to occasionally stand on two legs.

Tail function

Tereschenko proposed that protoceratopsids were actually aquatic, using their laterally-flattened tails as a paddle to aid in swimming. According to Tereschenko, Bagaceratops was fully aquatic while Protoceratops was only partially aquatic.[1]

Paleoenvironment

Protoceratopsids likely lived in highly arid regions. Specimens are often found in

Paleobiogeography

Protoceratopsids have so far been found in rocks from the

See also

References

- ^ S2CID 84366476.

- ^ a b Osmolska, Halszka (1986). "STRUCTURE OF NASAL AND ORAL CAVITIES IN THE PROTOCERATOPSID DINOSAURS (CERATOPSIA, ORNITHISCHIA)". Paleontologica. 31 (1–2): 145–157.

- .

- S2CID 84639150.

- hdl:2246/4670.

- ^ Maryańska, T.; Osmólska, H. (1975). "Protoceratopsidae (Dinosauria) of Asia" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 33: 134−143.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-253-33907-2.

- ^ Sereno, P. C. (2000). "The fossil record, systematics and evolution of pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians from Asia" (PDF). In Benton, M. J.; Shishkin, M. A.; Unwin, D. M.; Kurochkin, E. N. (eds.). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. p. 489−492.

- hdl:2246/5808.

- S2CID 202867827.

- ^ Alifanov, V. R. (2003). "Two new dinosaurs of the infraorder Neoceratopsia (Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Nemegt depression, Mongolian People's Republic". Paleontological Journal. 37 (5): 524–534.

- S2CID 132780322.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-253-35358-0.

- ^ PMID 25951329.

- ISSN 1937-2337.

- S2CID 129085129.

- PMID 25426957.

- ISBN 978-0-521-71902-5.

- JSTOR 3515294.

- .

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.