Rhenish Republic

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

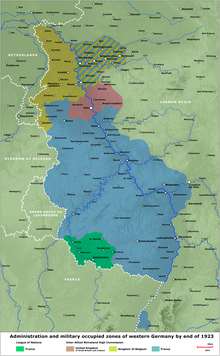

Rhenish Republic Rheinische Republik | |

|---|---|

| 1923 | |

|

Flag | |

| Status | Unrecognized state |

| Capital | Aachen |

| Demonym(s) | Rhenish |

| Government | Republic |

| History | |

• Established | 21 October 1923 |

• Disestablished | 26 November |

| Today part of | Germany |

The Rhenish Republic (

.Background

The Rhenish Republic is best understood as the aspiration of a poorly focused liberation struggle.[

Rhenish separatism in the 1920s should be seen in the context of resentments fostered by

After 1924, economic hardship slowly began to ease and a measure of brittle stability returned to Germany under the Weimar State. The appeal of Rhenish separatism, never a mass movement, was damaged by the violence employed by many of its more desperate supporters. The political temperature cooled after the French occupation of the Ruhr attracted increasingly strident criticism from Britain and the United States. Following the Dawes Plan in September 1924, an agreement to a slightly less punitive war reparations payment régime, the French vacated the Ruhr in the summer of 1925. The end of the Rhenish Republic can be dated at December 1924, when its leading instigator, Hans Adam Dorten (1880–1963), was obliged to flee to Nice. By 1930, when French troops also vacated the left bank of the Rhine, the concept of a Rhenish Republic, independent of Berlin, no longer attracted popular support.

Historical context

The

Chronology

Dr Adenauer calls a meeting

On 1 February 1919, more than sixty of the Rhineland's civic leaders together with locally based Prussian National Assembly Members convened in

In addressing delegates, Adenauer identified the wreckage of Prussian hegemonistic power as the "inevitable consequence" ("notwendige Folge") of the Prussian system. Prussia was viewed by opponents as "Europe's evil spirit" and was "ruled over by an unscrupulous caste of war-fixated militaristic aristocrats" ("von einer kriegslüsternen, gewissenlosen militärischen Kaste und dem Junkertum beherrscht"). He said that the other German states should, therefore, no longer put up with Prussian supremacy, that Prussia should be divided up, and the western provinces separated out to form a "West German Republic". This would make future domination of Germany by Prussia's eastern militaristic ethos impossible. Adenauer was, however, keen that this West German Republic should remain inside the German political union.

In the end, the Cologne meeting produced a two-point resolution. The meeting asserted the right of the Rhineland peoples to political self-determination. The proclamation of a West German Republic was to be deferred, however, so that the Prussian state might be divided up. In this way a practical solution could first be agreed with the French occupiers and France's allies regarding the issue of reparations.

During the months following Adenauer's meeting, separatist movements with a range of priorities and agendas appeared in many Rhineland towns and villages.

Hans Adam Dorten and the Wiesbaden Proclamation

At liberty, Dorten continued his struggle: on 22 January 1922 he founded in

Occupation of the Ruhr

The German government fell into arrears with war reparations payments. In response, on 8 March 1921,

The occupation of the Ruhr coincided with, and in the view of many commentators triggered, a tipping point for the

"Government" in Koblenz: Separatism across the Rhineland

Two months later, ten kilometres to the east of

Meanwhile, in Aachen itself, separatists led by Leo Deckers and Dr Guthardt captured the

On 25 October, the local police were placed under the command of the Belgian occupation forces after attempting to storm the separatists out of the government buildings, only to find themselves thwarted by occupation troops. Across town, changes at the Technical High School included the exclusion from Aachen of non-resident students.

On 2 November, the Rathaus was retaken by the separatists, now reinforced by around 1000 members of the "Rhineland protection force" (der Rheinland-Schutztruppen). Belgian High Commissar, Baron Rolin-Jaquemyns, responded by ordering an immediate end to the separatist government and called the troops off the streets. The City Council convened in the evening and swore loyalty to the German State (Treuebekenntnis zum Deutschen Reich).

Parallel coup attempts in many Rhenish towns blew up, most of them following much the same pattern.

To the north, in Duisburg, separarists inaugurated, on 22 October 1923 a mini-state that would endure for five weeks. Local members of the Rhenish Independence League took to the streets, proclaiming, disingenuously, that their new republic had come into being without any input from the French: attempts to suppress the Duisburg republic more rapidly were nonetheless blocked by the French occupation forces.

Back in Koblenz, the regional capital, separatists had tried to seize power on 21 October 1923. The next day saw hand-to-hand fighting involving the local police. During the night of 23 October,

On 26 October, the French High Commissioner, Paul Tirard, confirmed that the separatists were in possession of effective power (als Inhaber der tatsächlichen Macht). Subject to the self-evident superior authority of the occupiers, he stated that they needed to introduce all the necessary measures (alle notwendigen Maßnahmen einleiten). Separatist leaders Dorten and Josef Friedrich Matthes interpreted Tirard's intervention as an effective

The new government's power was heavily dependent on finance and support from the French occupation force, as well as on the separatists' own Rhineland Protection Force, which was primarily recruited from men expelled from their homes by the French militarisation of the Ruhr. The "protection force" was poorly equipped: many members were too young to have received any military training. Their implementation of the new government's orders, in the absence of detailed instructions, was rough and ready at best, and sometimes violent. A night-time

From his occupation headquarters in Mainz, General Mangin would no doubt have had a far more richly calibrated appreciation of the possibilities presented by Rhenish separatism than the ministers in far away Paris: it is possible to infer, between the approach of the French commanders on the ground and priorities of the Poincaré government, a disparity which became impossible to overlook once Dorten launched his coup in Koblenz: at the same time Paris was coming under heavy political pressure internationally over the increasingly costly French occupation of the Ruhr. In Koblenz, cabinet meetings were often combative and confused, the leaders Dorten and Matthes proving unable to contain their personal rivalries. The French power-brokers now quickly distanced themselves from the Rhenish Republic project, drastically cutting back on their financial support. The Matthes government issued Rhenish bank notes and ordered an extensive "Requisitioning" exercise: this was the signal for the Rhineland Protection Force to embark upon a level of arbitrary widespread looting which greatly exceeded anything necessary simply for feeding the hungry "protection troops". In many towns and villages the situation slid towards chaos. The civil population became increasingly hostile, and the French military found themselves attempting, with increasing difficulty, to preserve some level of order.

Between 6 and 8 November, a force of Rhineland Protection Force members, calling themselves the Northern Flying Division (Fliegende Division Nord), launched an attack on

10 November saw an outburst of looting at

On 12 November, the separatists gathered together close by in Bad Honnef, there intending to establish a new headquarters. The Rathaus was taken over and, two days later, the Rhenish Republic proclaimed. Food and liquor were seized in numerous hotels and residences and a large celebration took place in the Kurhaus (Health and Recreation Spa center), during which the Kurhaus furnishings went up in flames.

Siebengebirge insurrection

The Siebengebirge district consists of a series of low wooded hills wedged between the

It was thought that Schneider's Aegidienberg-based force now comprised about 4000 armed men. Using factory sirens and alarm bells, the local troops would be mobilised the minute separatist forces were reported or even merely rumoured to have appeared. Panic was apparent as people rushed around trying to move to safety their cattle and other chattels.

During the afternoon of 15 November, a group of separatists drove two trucks into the Himberg quarter of Aegidienberg: here they were confronted by around 30 armed quarry workers. Peter Staffel, an 18-year-old blacksmith, was shot dead when he forced the trucks to stop and tried to persuade the occupants to turn back. The quarry workers thereupon showered bullets on the separatists who turned and fled along the little Schmelz valley. As they fled down the twisting road, back towards Bad Honnef, they encountered the local militia, well dug in and waiting for them: Schneider's men seized the trucks and then routed the separatist gang.

That evening the repulsed separatists met up at the Gasthof Jagdhaus, down the Schmelz valley, and called up reinforcements. They planned a more substantial attack for the next day, in order to make an example of Aegidienberg. Accordingly, on 16 November, some 80 armed separatists found a gap in Schneider's defences at a hamlet called Hövel: here they seized five villagers as hostages, tied them up, and placed them in the line of fire between themselves and the now-gathering militiamen. One of the hostages, Theodor Weinz, was shot in the stomach, dying soon afterwards as a result of his injuries.

Meanwhile, more local defenders hurried to the fray and set about the invaders. 14 of the separatists were killed: these were later buried in a mass grave back in Aegidienberg, without the benefit of any identifying inscription. According to contemporaries, the dead men had come originally from the Kevelaer and Krefeld areas, between the Ruhr and the Dutch border.

In order to prevent further fighting, the French installed in Aegidienberg a force of French-

End of the Rhenish Republic

Following the events in Aegidienberg, the separatist cabinet based at the castle in Koblenz split into two camps. Across the province separatist governments were evicted from the Rathausen and in some instances arrested by the French military. Leo Deckers resigned his office on 27 November. On 28 November 1923, Matthes announced that he had dissolved the separatist government.[2] Dorten had already, on 15 November, moved to Bad Ems and there established a provisional government covering the southern part of the Rhineland and the Palatinate and participated actively in the activities of the "Pfälzische Republik" movement, centred on Speyer, which would survived through till 1924. At the end of 1923, Dorten fled to Nice: later he relocated to the US, where he published his memoirs; Dorten was still in exile when he died in 1963.

Joseph Matthes also made his way to France where he later met up with fellow journalist Kurt Tucholsky. Despite the amnesty set out in the London Agreement of August 1924, Matthes and his wife were prevented from returning to Germany, leading Tucholsky to publish in 1929 his essay entitled For Joseph Matthes, from which are drawn his observations on conditions in the Rhineland in 1923, cited above.

In the towns, the remaining separatist Burgermeister found themselves voted out of office at the end of 1923 or were, for their activities, before the courts.

Konrad Adenauer, who during the period of the "Koblenz Government" had constantly been at odds with Dorten, presented to the French generals another proposal, for the creation of a west German autonomous federal state (die Bildung eines Autonomen westdeutschen Bundesstaates). Adenauer's proposal failed to impress either the French or the German government at this time, however.

See also

- Separatism in Europe

- Republic of Mainz

- Cisrhenian Republic

- Free State of Bottleneck

- Grand Duchy of Berg

- Territory of the Saar Basin

- Ruhr Question

- Flag of North Rhine-Westphalia

- Josef Friedrich Matthes

- Franz Josef Heinz

References

- ISBN 978-3-644-10026-8. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- New York Times. 29 November 1923. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

Joseph Matthes chief of the "Rhineland Republic," announced today that he had dissolved the Separatist Government at Coblenz. He is back at Dusseldorf, where he told the New York Times correspondent he intended "to start the movement afresh along better lines, freed from compromising elements which had done no much to discredit it."