SMS Regensburg

Postcard depicting a sketch of Regensburg

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Regenseburg |

| Namesake | City of Regensburg |

| Builder | AG Weser, Bremen |

| Laid down | 1912 |

| Launched | 25 April 1914 |

| Commissioned | 3 January 1915 |

| Stricken | 10 March 1920 |

| Fate | Ceded to France |

| Name | Strasbourg |

| Namesake | City of Strasbourg |

| Acquired | 4 June 1920 |

| Out of service | 14 June 1936 |

| Fate | Scuttled in Lorient, 1944 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Graudenz-class cruiser |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 142.7 m (468 ft 2 in) |

| Beam | 13.8 m (45 ft 3 in) |

| Draft | 5.75 m (18 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 27.5 kn (50.9 km/h) |

| Range | 5,500 nmi (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) at 12 kn (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Crew |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Regensburg was a

Regensburg served in the reconnaissance forces of the

Design

Regensburg was 142.7 meters (468 ft)

The ship was armed with twelve

Service history

Regensburg was ordered under the contract name "

On 17–18 May, Regensburg took part in a mine-laying operation in the area of the Dogger Bank. On 25 August, she went into the Baltic to bombard Russian positions again, this time on the island of Dagö, including the lighthouse in St. Andreasberg and the signal station on Cap Ristna. On 11–12 May, Regensburg participated in another mine-laying operation, this time off Texel. In September, she took part in anti-shipping sweeps in the Skagerrak and the Kattegat. In early 1916, she continued supporting mine-laying operations and reconnaissance sweeps into the North Sea. On 23–24 April, she participated in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft, conducted by the battlecruisers of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's I Scouting Group.[4]

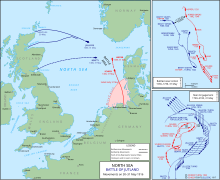

Battle of Jutland

In May 1916, Admiral Reinhard Scheer, the fleet commander, planned to lure a portion of the British fleet away from its bases and destroy it with the entire High Seas Fleet. For the planned operation, Regensburg, commanded by Commodore Paul Heinrich, was assigned to serve as the leader of the torpedo boat flotillas that screened for the battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group. The squadron left the Jade roadstead at 02:00 on 31 May, bound for the waters of the Skagerrak. The main body of the fleet followed an hour and a half later. At around 15:30, the cruiser screens of the I Scouting Group and the British 1st Battlecruiser Squadron engaged; Regensburg was on the disengaged side of the German formation, but steamed to reach the head of the line of battle. As she was moving into position, the opposing battlecruisers opened fire; Regensburg was some 2,200 yd (2,000 m) from the German battlecruisers, still on the disengaged side. Her crew noted that the British shells were falling well over their targets, which placed Regensburg in greater danger than the battlecruisers at which the British were aiming. By 17:10, Regensburg had reached the head of the line, and the battlecruiser HMS Tiger fired several salvos at her, mistaking her for a battlecruiser.[6]

As the battlecruiser squadrons closed on each other, Regensburg ordered the torpedo boats to make a general attack on the British formation. The British had similarly ordered an attack with their destroyers, which led to a hard-fought battle at close range between the opposing destroyer forces, supported by light cruisers and the battlecruisers' secondary guns. Shortly after 19:00, Regensburg led an attack with several torpedo boats on the cruiser Canterbury and four destroyers. She disabled the destroyer Shark and then shifted fire to Canterbury, which turned away into the mist. By 20:15, the British and German main fleets had engaged, and Scheer sought a withdrawal; he therefore ordered the I Scouting Group to charge the British line while the rest of the fleet turned away. This was in turn covered by a massed torpedo boat attack, which forced the British to turn away as well. Regensburg and her torpedo boats were ordered to join the attack, but the I Scouting Group had passed in front of his ships, and he realized the British had turned away, which put them out of range of his torpedoes.[7]

Having successfully disengaged, Scheer ordered Regensburg to organize three torpedo boat flotillas to make attacks on the British fleet during the night. At 21:10, Heinrich dispatched the II Flotilla and XII Half-Flotilla from the rear of the German line to attack the British formation. In the night, the High Seas Fleet successfully passed behind the British fleet and reached

Subsequent operations

By 1917, Regensburg had been assigned to the IV Scouting Group, along with Stralsund and Pillau. In late October 1917, the IV Scouting Group steamed to Pillau, arriving on the 30th. They were tasked with replacing the heavy units of the fleet that had just completed Operation Albion, the conquest of the islands in the Gulf of Riga, along with the battleships of the I Battle Squadron. The risk of mines that had come loose in a recent storm, however, prompted the naval command to cancel the mission, and Regensburg and the rest of the IV Scouting Group was ordered to return to the North Sea on 31 October.[9]

By October 1918, Regensburg was serving as the

As the mutinies spread, Regensburg was sent to

French service

Regensburg served in the newly reorganized

She was initially home-ported in Brest, until she was transferred to Toulon in 1923, where she remained for the next three years.[16] Here, she served with the other ex-German cruisers Mulhouse and Metz and the ex-Austro-Hungarian Thionville in the 3rd Light Division (which was renamed the 2nd Light division in December 1926).[15] In 1925, she underwent a major overhaul, after which she made 26 kn (48 km/h; 30 mph) on speed trials.[17] Strasbourg participated in the Rif War in the mid-1920s; on 7 September 1925, she and the battleship Paris and the cruiser Metz supported a landing of French troops in North Africa. The three ships provided heavy gunfire support to the landing troops.[18] In early 1928, a major earthquake struck Corinth, Greece; Strassbourg was among the vessels sent to aid in the relief effort. The international effort provided assistance to 15,000 people.[19]

Also in 1928, she assisted in the search effort for the wrecked

She remained in service until 14 June 1936, when she was placed in reserve. Her name was reused for the new battleship

Footnotes

- ^ a b Gröner, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, pp. 140, 161.

- ^ Gröner, p. 109.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 60.

- ^ Woodward, p. 35.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 62, 75, 90, 99.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 101, 130–131, 181–185.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 186–187, 202, 246–247, 260, 292, 296.

- ^ Staff, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Woodward, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 280–282.

- ^ Woodward, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 62.

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 110.

- ^ a b Dodson, p. 151.

- ^ Maurette & Moriceau, p. 18.

- ^ Smigielski, p. 201.

- ^ Álvarez, p. 185.

- ^ a b Maurette & Moriceau, p. 19.

- ^ The Daily News Almanac and Political Register, p. 443.

- ^ Dodson, pp. 151, 157.

- ^ Maurette & Moriceau, pp. 19–20.

References

- Álvarez, José E. (2001). The Betrothed of Death: The Spanish Foreign Legion During the Rif Rebellion, 1920–1927. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30697-4.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- ISBN 978-1-8448-6472-0.

- ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 7. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 9783782202671.

- Maurette, Jean-Louis & Moriceau, Christophe (2008). Épaves en baie de Lorient (in French). Gourin: Éditions des Montagnes Noires. ISBN 978-2-919305-07-0.

- Smigielski, Adam (1986). "France". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 190–220. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Staff, Gary (2008). Battle for the Baltic Islands. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84415-787-7.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

- Woodward, David (1973). The Collapse of Power: Mutiny in the High Seas Fleet. London: Arthur Barker Ltd. ISBN 978-0-213-16431-7.

- The Daily News Almanac and Political Register. 45. Chicago: Chicago Daily News Co. 1929. )

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.

- ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.