Sa'd al-Dawla

| Sa'd al-Dawla سعد الدولة | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Emir of Aleppo | |||||

| Reign | 967–991 | ||||

| Predecessor | Sayf al-Dawla | ||||

| Successor | Sa'id al-Dawla | ||||

| Born | 952 | ||||

| Died | December 991 Aleppo, Syria | ||||

| |||||

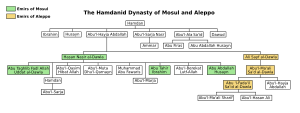

| Dynasty | Hamdanid | ||||

| Father | Sayf al-Dawla | ||||

| Mother | Sakhinah | ||||

| Religion | Shia Islam | ||||

Abu 'l-Ma'ali Sharif, more commonly known by his

Biography

Early years

Sa'd al-Dawla was the son of

Sa'd al-Dawla reached Aleppo, which for years had been governed by Sayf al-Dawla's chief minister and chamberlain (

The year 969 was a crucial one in Syrian history, as it marked the climax of the Byzantine advance. In October, the generals

Recovery of Aleppo

It was not until 977 that Sa'd al-Dawla managed to regain his capital, which by now was under the control of Bakjur, who in 975 had deposed and imprisoned Qarquya. Aided by some of his father's ghilman, and, crucially, the powerful Banu Kilab tribe living around Aleppo, Sa'd al-Dawla besieged Aleppo and captured it. Qarquya was set free and again entrusted with the affairs of state until his death a few years later, while Bakjur was given the governorship of Homs.[1][6][7]

Soon after, in 979, he was able to capitalize upon Abu Taghlib's conflict with the

Conflicts with Bakjur, the Fatimids and Byzantium

Bakjur, in the meantime, had used his new post at Homs to open contacts with the Fatimids, who intended to use him as a pawn to subdue Aleppo and complete their conquest of the entirety of Syria.[8] Sa'd al-Dawla himself oscillated between the Fatimids and Byzantium: on the one hand he resented Byzantine overlordship and was willing to acknowledge the Fatimid Caliph, but on the other hand he did not want to see his domain become merely another Fatimid province like southern Syria.[7]

His first attempt to free himself of the Byzantine protectorate, in 981, ended in failure due to lack of outside support, when a Byzantine army appeared before Aleppo's walls to enforce compliance.[7][8] The Fatimids then induced Bakjur to act: in September 983, Bakjur launched an attack on Aleppo with the support of Fatimid troops. Sa'd al-Dawla was forced to appeal to the Byzantine emperor Basil II for help, and the siege was raised by a Byzantine army under Bardas Phokas the Younger. The Byzantines then proceeded to sack Homs in October. The city was returned to Hamdanid control, while Bakjur fled to Fatimid territory, where he assumed the governorship of Damascus.[7][8][9][10] It is an indication of the strained relations between Sa'd al-Dawla and his "saviours" that after Bakjur's flight, there were clashes between Byzantine and Hamdanid troops, which were settled only when the Hamdanid emir agreed to pay twice the usual yearly amount of tribute of 20,000 gold dinars.[7]

Hamdanid relations with Byzantium collapsed completely in 985–986, after the Fatimids took the Byzantine fortress of

Warfare with the Fatimids once again threatened in 991, again because of Bakjur. He had governed Damascus until 988, when he was deposed, and then fled to Raqqa. From there, though with little support from the Fatimids, he tried to attack Aleppo. With Byzantine assistance in the form of troops under the

Succession and the end of the Hamdanid dynasty in Aleppo

Sa'd al-Dawla was succeeded by his son,

References

- ^ a b c d e f Canard 1971, p. 129.

- ^ a b El Tayib 1990, p. 326.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 277–280.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2004, p. 280.

- ^ Canard 1971, pp. 127–128, 129.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 280–281.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stevenson 1926, pp. 250.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Canard 1971, p. 130.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 281.

- ^ Whittow 1996, p. 367.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 367–368.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 369–373.

- ^ Stevenson 1926, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 379–380.

- ^ Stevenson 1926, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 379–381.

Bibliography

- OCLC 495469525.

- El Tayib, Abdullah (1990). "Abū Firās al-Ḥamdānī". In Ashtiany, Julia; Johnstone, T. M.; Latham, J. D.; Serjeant, R. B.; Smith, G. Rex (eds.). ʿAbbasid Belles-Lettres. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 315–327. ISBN 0-521-24016-6.

- ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Stevenson, William B. (1926). "Chapter VI. Islam in Syria and Egypt (750–1100)". In Bury, John Bagnell (ed.). The Cambridge Medieval History, Volume V: Contest of Empire and Papacy. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 242–264.

- ISBN 978-0-520-20496-6.