Simraungadh (medieval city)

| Simraungadh | |

|---|---|

| Native name Hindi: सिमरौनगढ़ | |

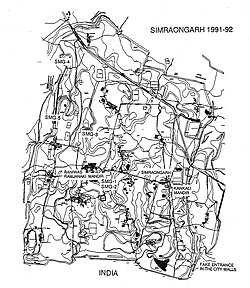

Location of the medieval city of Simraungadh on the India-Nepal border following archaeological excavations | |

| Founded | 11th century |

| Demolished | 1324 |

Simraungadh, (also referred to as Simramapura, Simraongarh or Simroungarh) (/ˈsiːmraʊnɡɜːr/, Devanagari: सिम्रौनगढ) was a fortified city[1] and the main capital of the Karnats of Mithila,[2] founded by its first ruler, Nanyadeva[3] in 1097.[4][5][6] At the present time, the excavations show that the city is located on the India-Nepal border. There is also a municipality by the same name in Nepal.[7] The archaeological site is currently split between

History

The remains are still scattered all over the Simroungarh region. King Harisingh Deva fled northwards into the then Nepal. The son of Harisingh Dev, Jagatsingh Dev married Nayak Devi, the widowed princess of Bhaktapur.[16]

Medieval city plan and fortification

The medieval city of Simraungadh was enclosed within an impressive system of earthen ramparts and infilled ditches.[17] The fortification of the medieval city has a rectangular shape and ground plan. The fortifications of Simraungadh are called Baahi locally[18] and remembered as a Labyrinth.[7] The fort is spread in 6 Kos[19] and the main enclosure is about 7.5 km north–south and 4.5 km east–west. The eastern and western sides of the fort were built over two natural embankments. The western side of the fort was dry in comparison to the eastern side.[9] The Labyrinth and the powerful defence system of the city were well planned to protect from the river floods, and enemies and regulate agriculture from controlled flow of water from the ditches showing the ability of the Kingdom.

During the reign of

After the fall and decline of the Karnat dynasty from Simraungadh, There were some old ruins, and some seemed to be remains of substantial buildings. The city was situated in the quasi-labyrinth enclosed by high walls and was impossible to enter except in a single spot. There were four fortresses, which were evenly distributed from place to place within the enclosures of the labyrinth; and these enclosures had a distance from one side to the other of about a Kos or two miles, and the walls were extremely high with a width in proportion.[23]

Gallery

-

Simraungadh Toran Dwar Statue

-

Pillar at Simraungadh

-

Statue of Brahma from Simraungadh at National Museum Kathmandu

-

12th century Stone Inscription from Simraungadh in Tirhuta script

-

Simraungadh Brahma statue

-

Statue of theBuddhafound at Simraungadh

-

Dvarapala found at Simraungadh

-

Shiva found at Simraungadh

-

Statue of Garuda

-

Bhairava statue

References

- ^ Lunden, Staffan (1994). "A Nepalese Labyrinth" (PDF). Caerdroia. 26: 13–21.

- ^ Jha, Makhan (1982). Civilizational Regions of Mithila & Mahakoshal. Capital Publishing House.

- ^ Sinha, Chandreshwar Prasad Narayan (1979). Mithila Under the Karnatas, C. 1097-1325 A.D. Janaki Prakashan.

- ISBN 9789380538280.

- ^ Cimino Maria, Rosa (August 1986). "Simraongarh The forgotten city and its art" (PDF). Contribution to Nepalese Studies. 13 (3): 277–288. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Garbini, Riccardo (October–November 1993). "A Fragmentary Inscription From Simraongarh, The Ancient Mithila Capital" (PDF). Ancient Nepal (135): 1–9. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ a b Vidale, M; Lugli, F (1992). "Archaeological Investigation at Simraongarh" (PDF). Ancient Nepal: 2. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ISBN 9780199489558.

- ^ a b Vidale, M.; Balista, C.; Torrieri, V. (October–November 1993). "A Test Trench Through the Fortifications of Simraongarh" (PDF). Ancient Nepal (135): 10–21. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- JSTOR 23350289.

- ^ Choudhary, Radhakrishna (1970). History of Muslim rule in Tirhut, 1206-1765, A.D. Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office.

- ^ Thapa, Netra Bahadur (1981). A Short History of Nepal (PDF). Ratna Pustak Bhandar. pp. 38–39.

- ^ Abdusi Akhsatan Dehlavi, Mohammad bin Sadr Taj (1301–1335). "Basatin-Ul Uns". Center for Persian Research: XXI.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Abdul Malik Isami (1981). "Futuh-us-Salatin". University of Madras: 38–39.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Firishtah, Muḥammad Qāsim Hindū Shāh Astarābādī (1829). History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India, Till the Year A.D. 1612. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green.

- ^ "Simroungarh | Nepal | Heritage & Archaeological Site".

- ^ Khanāla, Mohanaprasāda (1999). Simaraunagaḍhako itihāsa [History of Simraungadh] (in Nepali). Nepāla ra Eśiyālī Anusandhāna Kendra, Tribhuvana Viśvavidyālaya.

- ^ "बारा जिल्लाको ऐतिहासिक पर्यटकीय गन्तव्य सिम्रौनगढ" [Simraungadh is a historical tourist destination of Bara district]. nepalpatra.com (in Nepali). Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ^ Sharma, Janak Lal (January 1968). "चितवनदेखि जनकपुरसम्मका केही पुरातात्विक स्थल" [Some archeological sites from Chitwan to Janakpur] (PDF). Ancient Nepal (in Nepali) (2): 1–10. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Giri, Sheetal. "डोय राज्यको स्थापना र पतन" [Rise and fall of Doy Kingdom]. Nagarik News (in Nepali). Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ^ Subedi, Rajaram (2006). "Historical Entity of Vijayapur State": 27–28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - OCLC 244248214.

- ^ Lundén, Staffan (June 1998). "A Nepalese Labyrinth". Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO). 48 (1/2): 117–134. Retrieved 11 March 2021.