Thomas Dudley

Thomas Dudley | |

|---|---|

| 3rd, 7th, 11th, and 14th John Endicott | |

| In office 1649–1649 Serving with Simon Bradstreet | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 October 1576 Yardley Hastings, Northamptonshire, England |

| Died | 31 July 1653 (aged 76) Roxbury, Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Spouses | Dorothy Yorke

(m. 1582; died 1643)Katherine Hackburne (m. 1644) |

| Parent |

|

| Profession | Colonial administrator, governor |

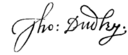

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of England |

| Branch/service | Forces of William Compton, 1st Earl of Northampton |

| Battles/wars | |

Thomas Dudley (12 October 1576 – 31 July 1653) was a

The son of a military man who died when he was young, Dudley saw military service himself during the French Wars of Religion, and then acquired some legal training before entering the service of his likely kinsman, the Earl of Lincoln. Along with other Puritans in Lincoln's circle, Dudley helped establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony, sailing with Winthrop in 1630. Although he served only four one-year terms as governor of the colony, he was regularly in other positions of authority.

Dudley's daughter Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672) was a prominent early American poet. One of the gates of Harvard Yard, which existed from 1915 to 1947, was named in his honor, and Harvard's Dudley House is named for the family, as is the town of Dudley, Massachusetts.

Early years

Thomas Dudley was born in

Like many other young men of good birth Thomas Dudley became a

After he was discharged from his military service, Dudley returned to Northamptonshire.

Dudley was briefly out of Lincoln's service between about 1624 and 1628. During this time, he lived with his growing family in

Massachusetts Bay Colony

In 1628 Dudley and other Puritans decided to form the

Dudley and his family sailed for the New World on the

Founding of Cambridge

In the spring of 1631, the leadership agreed to establish the colony's capital at Newtowne (near present-day Harvard Square in Cambridge), and the town was surveyed and laid out. Dudley, Simon Bradstreet, and others built their houses there, but to Dudley's anger, Winthrop decided to build in Boston. This decision caused a rift between Dudley and Winthrop; it was severe enough that in 1632 Dudley resigned his posts and considered returning to England.[25] After the mediation of others, the two reconciled, and Dudley retracted his resignation. Winthrop reported that "[e]ver after they kept peace and good correspondency in love and friendship."[26] During the dispute, Dudley also harshly questioned Winthrop's authority as governor for several actions without consulting his council of assistants.[27] Dudley's differences with Winthrop came to the fore again in January 1636, when other magistrates orchestrated a series of accusations that Winthrop had been overly lenient in his judicial decisions.[28]

In 1632 Dudley, at his own expense, erected a

The colony came under legal threat in 1632, when Sir

Anne Hutchinson affair

In 1635, and for the four following years, Dudley was elected either as deputy governor or as a member of the council of assistants. The governor in 1636 was

Vane was turned out of office in 1637 over the Hutchinson affair and his insistence on flying the

Although Dudley and Winthrop clashed with each other on several issues, they agreed on banning Hutchinson, and their relationship had some significant positive elements. In 1638 Dudley and Winthrop were each granted a tract of land "about six miles from Concord, northward".[41] Reportedly, Winthrop and Dudley went to the area together to survey the land and select their parcels. Winthrop, then governor, graciously deferred to Dudley, then deputy governor, to make the first choice of land. Dudley's land became Billerica, and Winthrop's Bedford.[41] The place where the two properties met was marked by two large stones, each carved with the owner's name; Winthrop described the spot as the "'Two Brothers', in remembrance that they were brothers by their children's marriage".[42]

Other political activities

During Dudley's term of office in 1640, many new laws were passed. This led to the introduction the following year of the

In 1649 Dudley was appointed once again to serve as a commissioner and president of the New England Confederation, an umbrella organization established by most of the New England colonies to address issues of common interest; however, he was ill (and aging, at 73), and consequently unable to discharge his duties in that office.[46] Dudley was elected governor for the fourth and last time in 1650 despite the illness.[47] The most notable acts during this term were the issuance of a new charter for Harvard College,[48] and the judicial decision to burn The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption, a book by Springfield resident William Pynchon that expounded on religious views heretical to the ruling Puritans. Pynchon was called upon to retract his views but returned to England instead of facing the magistrates.[49]

During most of his years in Massachusetts, when not governor, Dudley served as either deputy governor or as one of the colony's commissioners to the New England Confederation.

Nathaniel Morton, an early chronicler of the Plymouth Colony, wrote of Dudley, "His zeal to order appeared in contriving good laws, and faithfully executing them upon criminal offenders, heretics, and underminers of true religion. He had a piercing judgment to discover the wolf, though clothed with a sheepskin."[55] Early Massachusetts historian James Savage wrote of Dudley that "[a] hardness in public, and rigidity in private life, are too observable in his character".[55] In a more modern historical view, Francis Bremer observes that Dudley was "more precise and rigid than the moderate Winthrop in his approach to the issues facing the colonists".[56]

Founding of Harvard and Roxbury Latin

One of thy founders, him New-England know,

Who staid thy feeble sides when thou wast low,

Who spent his state, his strength, and years with care,

That after comers in them might have share.

In 1637, the colony established a committee "to take order for a new college at Newtown".[58] The committee consisted of most of the colony's elders, including Dudley. In 1638, John Harvard, a childless colonist, bequeathed to the colony his library and half of his estate as a contribution to the college, which was consequently named in his honor. The college charter was first issued in 1642, and a second charter was issued in 1650, signed by then-Governor Thomas Dudley,[58] who also served for many years as one of the college's overseers. Harvard University's Dudley House, now only an administrative unit located in Lehman Hall after the actual house was torn down, is named in honor of the Dudley family.[59] Harvard Yard once had a Dudley Gate bearing words written by his daughter Anne;[57] it was torn down in the 1940s to make way for construction of Lamont Library.[60] A fragment remains in Dudley Garden, behind Lamont Library, including a lengthy inscription in stone.[61][62]

In 1643, Reverend John Eliot established a school at Roxbury. Dudley, who was then living in Roxbury, gave significant donations of both land and money to the school, which survives to this day as the Roxbury Latin School.[63]

Family and legacy

Dudley married Dorothy Yorke in 1603 and had five or six children. Samuel, the first, also came to the New World and married Winthrop's daughter Mary in 1633, the first of several alliances of the Dudley-Winthrop family.[65] He later served as the pastor in Exeter, New Hampshire.[66] Daughter Anne married Simon Bradstreet, and became the first poet published in North America.[67][68] Patience, Dudley's third child, married a colonial militia officer Daniel Denison. The fourth child, Sarah, married Benjamin Keayne, a militia officer. This union was unhappy, resulting in the first reported instance of divorce in the colony; Keayne returned to England and repudiated the marriage. Although no formal divorce proceedings are known, Sarah eventually married again,[69] to Job Judkins, by whom she bore five children. Mercy, the last of his children with Dorothy, married minister John Woodbridge.[67]

Dudley may have had another son, though most historians think the evidence is too slim. A “Thomas Dudley” was awarded degrees from Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, in 1626 and 1630, and some historians have argued this is a son of Dudley. Also, Dudley was referred to as “Thomas Dudley Senior” on a lone occasion in 1637.[70]

Dorothy Yorke died on 27 December 1643 at 61 years of age, and was remembered by her daughter Anne in a poem:[71]

Here lies,

A worthy matron of unspotted life,

A loving mother and obedient wife,

A friendly neighbor, pitiful to poor,

Whom oft she fed and clothed with her store;

Dudley married his second wife, the widow Katherine (Deighton) Hackburne, a descendant of the noble Berkeley, Lygon, and Beauchamp families,[72] in 1644. She is also a direct descendant of eleven of the twenty-five barons who acted as sureties for John Lackland on the Magna Carta.[73] They had three children, Deborah, Joseph, and Paul.[67] Joseph served as governor of the Dominion of New England and of the Province of Massachusetts Bay.[74] Paul (not to be confused with Joseph's son Paul, who served as provincial attorney general) was for a time the colony's register of probate.[67]

In 1636, Dudley moved from Cambridge to Ipswich, and in 1639, moved to Roxbury.[75][76] He died in Roxbury on 31 July 1653, and was buried in the Eliot Burying Ground there. Dudley, Massachusetts is named for his grandsons Paul and William, its first proprietors.[77]

The

Dudley Square

A non-binding advisory question was added to the 5 November 2019 municipal ballot for all Boston residents asking, "Do you support the renaming/changing of the name of Dudley Square to Nubian Square?"[80] Election night results show that the question was defeated.[83]

Mayor of Boston Marty Walsh subsequently announced that the question had "passed in the surrounding areas" near the square, and could be considered further by the city's Public Improvement Commission.[84] On 19 December 2019, the Public Improvement Commission unanimously approved changing the name of Dudley Square to Nubian Square.[85][86] Dudley station was renamed Nubian station in June 2020.[87]

Notes

- ^ Anderson, p. 584

- ^ Jones, pp. 3–10

- ^ a b c d Richardson et al, p. 280

- ^ Anderson, p. 585

- ^ Jones, p. 3

- ^ Jones, p. 24

- ^ Kellogg, p. 3

- ^ Jones, p. 25

- ^ Jones, pp. 25–26

- ^ Jones, pp. 31–32

- ^ Jones, p. 40

- ^ Jones, p. 42

- ^ Kellogg, pp. 11–12

- ^ Kellogg, p. 8

- ^ Jones, pp. 44–46, 55

- ^ a b Hurd, p. vii

- ^ Jones, p. 73

- ^ Bailyn, pp. 18–19

- ^ Jones, pp. 59–60

- ^ Winthrop's Journal; Jones, pp 64,75

- ^ Jones, p. 78

- ^ Jones, pp. 83–84

- ^ Female Piety in Puritan New England: The Emergence of Religious Humanism, Amanda Porterfield, p. 89

- ^ Winthrop, John; Dudley, Thomas; Allin, John; Shepard, Thomas; Cotton, John; Scottow, Joshua (January 1696). "Massachusetts: or The First Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of Their Coming Thither, and Abode There: In Several Epistles (1696)". Joshua Scottow Papers. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ Moore, p. 283

- ^ a b c Moore, p. 284

- ^ Jones, pp. 109–110

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 245

- ^ Moore, p. 285

- ^ Moore, p. 286

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 234

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 240

- ^ Moore, pp. 287–288

- ^ Battis, pp. 232–48

- ^ Moore, p. 288

- ^ Jones, p. 226

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 298

- ^ Moore, pp. 317–318

- ^ Moore, pp. 6,320

- ^ Moore, p. 289

- ^ a b Jones, p. 251

- ^ Jones, p. 252

- ^ Jones, p. 271

- ^ Jones, p. 334

- ^ Bremer (2003), pp. 363–364

- ^ Jones, p. 389

- ^ Jones, p. 393

- ^ Jones, p. 394

- ^ Jones, p. 398

- ^ Hurd, p. ix

- ^ Hurd, p. x

- ^ Jones, p. 264

- ^ Bremer (2003), p. 238

- ^ Bremer, p. 239

- ^ a b Moore, p. 292

- ^ Bremer and Webster (2006), p. 79

- ^ a b Morison, p. 195

- ^ a b Jones, p. 243

- ^ Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 29, p. 365

- ^ Bunting and Floyd, pp. 216,319–320

- from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ Jones, p. 330

- ^ See e.g. the Auden genealogy entry for Thomas Dudley Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, and Google image search for "Thomas Dudley"

- ^ Jones, pp. 422,467

- ^ Jones, p. 467

- ^ a b c d Moore, pp. 295–296

- ^ Kellogg, p. xii

- ^ Jones, pp. 469–471

- ISBN 978-0-8063-0759-6.

- ^ Jones, p. 318

- ^ Ancestral Roots Of Certain American Colonists Who Came To America Before 1700, 8th edition, Frederick Lewis Weis, Walter Lee Sheppard, William Ryland Beall, Kaleen E. Beall, p.90

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Moore, pp. 391–393

- ^ Moore, p. 291

- ^ Jones, p. 256

- ^ Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, p. 12:412

- ^ "Massachusetts DCR Property Listing" (PDF). Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ "MACRIS listing for Two Brothers Rocks-Dudley Road" (PDF). Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ a b DeCosta-Klipa, Nik (19 September 2019). "Boston residents will get to vote on changing the name of Dudley Square. Here's why". Boston.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Daily Free Press Staff (6 November 2019). "Boston votes against renaming Dudley Square". The Daily Free Press. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ MacQuarrie, Brian (18 December 2019). "Dudley Square: at the intersection of Colonial history, African heritage". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ "BOSTON MUNICIPAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 2019". boston.gov. 3 October 2016. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Cotter, Sean Philip (15 November 2019). "Behind the 8 ball: Boston heads for City Council recount as margin just 8 votes". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ adamg (19 December 2019). "Dudley Square officially gets renamed Nubian Square". Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Cotter, Sean Philip (19 December 2019). "Roxbury's Dudley Square renamed Nubian Square". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Belcher, Jonathan. "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). Boston Street Railway Association.

References

- Anderson, Robert Charles (1995). The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England, 1620–1633. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society. OCLC 42469253.

- Bailyn, Bernard (1979). The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 257293935.

- Battis, Emery (1962). Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bremer, Francis (2003). John Winthrop: America's Forgotten Founder. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 237802295.

- Bremer, Francis; Webster, Tom (2006). Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: a Comprehensive Encyclopedia. New York: ABC-CLIO. OCLC 162315455.

- Bunting, Bainbridge; Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1985). Harvard: an Architectural History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 11650514.

- Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 29. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. 1981. OCLC 1751811.

- Hurd, Duane Hamilton, ed. (1890). History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Volume 1. Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis. from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Jones, Augustine (1900). The Life and Work of Thomas Dudley, the Second Governor of Massachusetts. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin. OCLC 123194823.

- Kellogg, D. B (2010). Anne Bradstreet. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. OCLC 527702802.

- Moore, Jacob Bailey (1851). Lives of the Governors of New Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Boston: C. D. Strong. p. 273. OCLC 11362972.

- OCLC 185403584.

- Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Historical Society, Volume 12. 1873. p. 412. OCLC 1695300.

- Richardson, Douglas; Everingham, Kimball; Faris, David (2004). Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company. OCLC 55848314.

Further reading

- Dudley, Dean (1848). The Dudley Genealogies and Family Records. Boston, MA: self-published. OCLC 3029090.

- Governor Thomas Dudley Family Association (1894). The First Annual Meeting of the Governor Thomas Dudley Association, Boston, Ma., 17 Oct. 1893. Boston, MA: self-published. OCLC 9274332.