User:Ifly6/Founding of Rome

![]() Founding of Rome

Founding of Rome

This page is a soft redirect.

The founding of Rome is a legendary event much embellished by later Roman myth. Archaeological evidence indicates that Rome was developed from earlier hilltop villages and was never so singularly founded. Habitation of the Italian peninsula goes back far into prehistory; evidence of settlement on the

Contrary to the gradual account given by material evidence, the Romans believed that their city was founded by the legendary king

Cultural context

The conventional division of pre-Roman cultures in Italy deals with cultures who spoke

When drawing a connection between peoples and their languages, a reconstruction emerges with Indo-European peoples arriving in various waves of migrations during the first and second millennia BC: first a western Italic group (including Latin), followed by a central Italic group of Osco-Umbrian dialects, with a late arrival of Greek and Celtic on the Italian peninsula, from across the Adriatic and Alps, respectively. These migrations are generally believed to have displayed speakers of Etruscan and other pre-Indo-European languages; although it is possible that Etruscan arrived also by migration, it must have done so before 2000 BC.[7]

The start of the Iron age saw a gradual increase in social complexity and population that led to the emergence of proto-urban settlements in central and northern Italy writ large. These proto-urban agglomerations were normally clusters of smaller settlements that were insufficiently distant to be separated communities; over time, they would unify.[8]

Archaeological evidence

The canonical Roman myth held that their city was founded by a Latin named Romulus some time around 750 BC on the 21 April.[9][10] Most modern historians and archaeologists largely ignore ancient Roman myths to focus on the archaeological evidence, which indicates that Rome had been occupied long before the ancients' c. 750 BC foundation date.[11]

Bronze and Iron ages

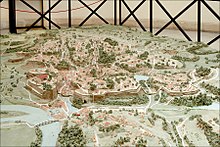

Contrary to ancient accounts, archaeological evidence suggests that Rome developed over a long period. The site of Rome was an attractive one for a city, as it controlled one of the sites to cross the Tiber between Etruria and Campania and also the salt beds at the Tiber's mouth. Traces of occupation also have been found in the general region – including in Lavinium and on the coast near Ardea – going back to the fifteenth century BC.[3]

The site that became Rome was definitely occupied by the middle of the

Evidence in the final Bronze age around 1200–975 BC is clearer and shows occupation of the Forum, Palatine, and Capitoline. Excavations near the modern

There are human remains by 1000 BC, with discovery of cremation graves in the forum.

Eighth and seventh centuries BC

By this time, four major settlements emerged in Rome. The nuclei appeared on the Palatine, the Capitoline, the Quirinal and Viminal, and the Caelian, Oppian, and Velia.[18] There is, however, no evidence linking any settlement on the Quirinal hill with the Sabines, as is alleged by some ancient accounts.[19]

The area of the Forum also was converted at this time into a public space. Burials there discontinued and portions of it were paved over. Votive offerings appear in the

The first evidence of a wall appears in the middle or late eight century on the Palatine, dated between 730 and 720 BC.[21] It is possible that the circuit of the wall marked out what later Romans believed to be the original pomerium (sacred boundary) of the city.[22] The discovery of gates and streets connected to the wall, with the remains of various huts, suggest that Rome had by this time:

acquired a defined boundary ... [and] a more sophisticated level of social and political organisation ... the use of the Forum as a public space point[s] to the development of [a] shared civil and ritual space[] for the inhabitants of all communities, demonstrating an increasing level of centralisation.[23]

Like other Villanovan proto-urban centres, this archaic Rome was likely organised around clans that guarded their own areas, but by the later eighth century had unified into a single polity.[23] The development of city-states was likely a Greek innovation that spread through the Mediterranean from 850 to 750 BC.[3][24] The earliest votive deposits are found in the early seventh century on the Capitoline and Quirinal hills, suggesting that by that time a city had formed with monumental architecture and public religious sanctuaries.[25] Certainly, by the end of the seventh century BC, a process of synoikismos was complete and there had been formed a unified Rome – reflected in the production of a central forum area, public monumental architecture, and civic structures – can be spoken of.[26]

Ancient tradition and founding myths

The Roman foundation stories are myths.[27] Even the name of the eponymous founder, Romulus, – translated as "Mr Rome" by Mary Beard – is now generally believed to have been retrojected from the city's name rather than reflecting a historical figure.[28] Some scholars, such as Andrea Carandini, have controversially suggested that these earliest myths reflect underlying historical events and that the city was in fact founded by a single actor as the Romans claimed; this theory is, according to Kathryn Lomas in the 2017 book Rise of Rome, "highly controversial" and based on highly tendentious interpretations of the archaeological evidence;[29] they have failed to gain wide acceptance.[30]

The Romans'

The canonical version of that myth is contained in the first book of Livy, which was written close to the end of the 1st century BC, some seven or eight centuries after the events the book purports to describe.[33] There are two main myths which were themselves developed through the centuries. The first relates to the foundation of the city by the brothers Romulus and Remus; the other to their mythical ancestor Aeneas.[23]

Chronological disagreements

| Ancient historian | Founding year |

|---|---|

| Gnaeus Naevius | c. 1100 BC[34] |

| Ennius | c. 1100 BC[35] or c. 884 BC[36][37] |

| Timaeus | 814–13 BC[38] |

| Calpurnius Piso | 757, 753, or 751 BC[39] |

| Varro | 754–53 BC[40] |

| Fasti Capitolini | 753–52 BC[41] |

| Dionysius of Halicarnassus | 752–51 BC[42][43] |

| Polybius | 751–50 BC[44][45] |

| Cato the Elder | 751 BC[46][47] |

Fabius Pictor

|

748–47 BC[48][49] |

| Cincius Alimentus | 729–28 BC[50] |

While the Romans believed that their city had been founded by an eponymous founder at a specific time,

The earliest years given, c. 1100 BC in the modern calendar, were based on the belief that Romulus was Aeneas' grandson, placing Rome's foundation much closer to fall of Troy, which at the time was dated, per Eratosthenes, 1184–83 BC.[34] This tradition is attested to as early as the fourth century BC. To solve the chronological problem, the Alban kings were interjected to reconcile the belief of Rome's foundation in the eighth century with the chronology of Troy.[48]

Romulus and Remus

According to the best-known version of the tale, Romulus and Remus are the grandsons of Numitor, the king of Alba Longa. After Numitor is deposed by his brother Amulius and his daughter Rhea Silvia is forced to become a virgin priestess for Vesta, she becomes pregnant – allegedly by Mars – and delivers the two illegitimate brothers.[53] Amulius orders that they be left to die on the slopes of the Palatine, but they are rescued by a she-wolf and then by a herdsman called Faustulus. Brought up by Faustulus and his wife Acca Larentia – who in Livy is a prostitute, as the Latin word lupa was slang therefor,[54] – the brothers reveal their true origins at adulthood and restore Numitor as king of Alba Longa, ejecting Amulius from the city. Afterwards, they leave and establish a city at the location they were rescued.[55][56]

Romulus kills Remus shortly thereafter amid a quarrel over naming rights and interpretation of auguries.[57] Stories differ: some say that Romulus killed his brother by his own hand while others attribute his death to a general fracas between their supporters.[58][59] Romulus, after laying out the city's boundaries, then declares it an asylum for exiles, criminals, and runaway slaves. The city becomes larger but also acquires a mostly male population.[60] When Romulus' attempts to secure the women of neighbouring settlements by diplomacy fail, he uses the religious celebration of Consualia to abduct the women of the Sabines. According to Livy, when the Sabines rally an army to take their women back, the women force the two groups to make peace and install the Sabine king Titus Tatius as co-monarch with Romulus.[55][61]

The story has been theorised by some modern scholars to reflect anti-Roman propaganda from the late fourth century BC, but more likely reflects an indigenous Roman tradition, given the Capitoline Wolf which likely dates to the sixth century BC. Regardless, by the third century, it was widely accepted by Romans and put onto some of Rome's first silver coins in 269 BC.[62] Cornell, in the 1995 book Beginnings of Rome, argues that the myths of Romulus and Remus are "popular expressions of some universal human need or experience" rather than borrowings from the Greek east or Mesopotamia, inasmuch as the story of virgin birth, intercession by animals and humble step-parents, with triumphant return expelling an evil leader are common mythological elements across Eurasia and even into the Americas.[63]

Aeneas

The indigenous tradition of Romulus was also combined with a legend telling of Aeneas coming from Troy and travelling to Italy. This tradition emerges from the Iliad's prophecy that Aeneas' descendants would one day return and rule Troy once more.[64] Greeks by 550 BC had began speculate, given the lack of any clear descendants of Aeneas, that the figure had established a dynasty outside the proper Greek world.[65] The first attempts to tie this story to Rome were in the works of two Greek historians at the end of the fifth century BC, Hellanicus of Lesbos and Damastes of Sigeum, likely only mentioning off hand the possibility of a Roman connection; a more assured connection only emerged at the end of the fourth century BC when Rome started having formal dealings with the Greek world.[66]

The ancient Roman annalists, historians, and antiquarians faced an issue tying Aeneas to Romulus, as they believed that Romulus lived centuries after the Trojan War, which was dated at the time c. 1100 BC. For this, they fabricated a story of Aeneas' son founding the city of Alba Longa and establishing a dynasty there, which eventually produced Romulus.[67][68][69]

In Livy's first book he recounts how Aeneas, a demigod of the Trojan royal Anchises and the goddess Venus, leaves Troy after its destruction during the Trojan War and sailed to the western Mediterranean. He brings his son – Ascanius – and a group of companions. Landing in Italy, he forms an alliance with a local magnate called Latinus and marries his daughter Lavinia, joining the two into a new group called the Latini; they then found a new city, called Lavinium. After a series of wars against the Rutuli and Caere, the Latins conquer the Alban Hills and its environs. His son Ascanius then founds the legendary city of Alba Longa, which became the dominant city in the region.[70] The later descendants of the royal lineage of Alba Longa eventually produce Romulus and Remus, setting up the events of their mythological story.[71]

Dionysius of Halicarnassus similarly attempted to show a Greek connection, giving a similar story for Aeneas, but also a previous series of migrations. He describes migrations of

The introduction of Aeneas follows a trend across Italy towards Hellenising their own early mythologies by rationalising myths and legends of the Greek Heroic Age into a pseudo-historical tradition of prehistoric times;[74] this was in part due to Greek historians' eagerness to construct narratives purporting that the Italians were actually descended from Greeks and their heroes.[75][71] These narratives were accepted by non-Greek peoples due Greek historiography's prestige and claims to systematic validity.[76]

Archaeological evidence shows that worship of Aeneas had been established at Lavinium by the sixth century BC.

Other myths

By the time of the Pyrrhic War (280–75 BC), there were some sixty different myths for Rome's foundation that circulated in the Greek world. Most of them attributed the city to an eponymous founder usually "Rhomos" or "Rhome" rather than Romulus.[81][82] One story, attributed to Hellanicius of Lesbos by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, says that Rome was founded by a woman named Rhome, one of the followers of Aeneas, after landing in Italy and burning their ships.[83] That by the middle of the fifth century Aeneas was also allegedly the founder of two or three other cities across Italy was no object.[84] These myths also differed as to whether their eponymous matriarch Roma was born in Troy or Italy – ie before or after Aeneas' journey – or otherwise if their Romus was a direct or collateral descendant of Aeneas.[85]

Myths of the early third century also differed greatly in the claimed genealogy of Romulus or the founder, if an intermediate actor was posited. One tale posited one Romus, son of Zeus, founded the city.[86] Callias posited that Romulus was descended from Latinus and a woman called Roma who was the daughter of Aeneas and a homonymous mother. Other authors depicted Romulus and Romus, here a son of Aeneas, founding not only Rome but also Capua. Authors also wrote their home regions into the story; Polybius, who hailed from Arcadia, for example, gave Rome not a Trojan colonial origin but an rather Arcadian one.[85]

References

Citations

- ^ Momigliano 1989, p. 57, citing Livy, 10.23.1.

- ^ a b c Lomas 2018, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Momigliano 1989, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Cornell 1995, p. 48.

- ^ Cornell 1995, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 43.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 44.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 17.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 35.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 72. Different ancient historians placed it in different years: "Fabius placed it in 748 BC, Cincius in 728, Cato in 751 and Varro in 754".

- ^ a b Momigliano 1989, p. 67.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 37.

- ^ Momigliano 1989, p. 54.

- ^ Bettelli 2012, para "The Capitoline hill and the earliest settlement in Rome in the Bronze Age".

- ^ Bettelli 2012, para "The early Iron Age and the occupation of the Palatine hill".

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 39.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 40; Cornell 1995, p. 57.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 41.

- ^ Momigliano 1989, pp. 86–87. "So far no archaeological support has been found for the self-assured Roman tradition that the Latins of Romulus soon combined with the Sabines... [or] that the Sabine settlement was on the Quirinal". Momigliano also notes a linguistic contradiction: Quirinal should in Oscan be Pirinal.

- ^ Lomas 2018, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Lomas 2018, p. 42.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Lomas 2018, p. 44.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 88.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 92; Cornell 1995, pp. 102–3.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 70.

- ^ Beard 2015, p. 71.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 36.

- ^ Cornell 1995, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 60.

- ^ Momigliano 1989, p. 83.

- ^ Livy, 1.

- ^ a b Koptev 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Momigliano 1989, p. 82. "Ennius... considered Ilia, Romulus' mother, to be the daughter of Aeneas... If, as seems probably, he attributed these words [that Rome was founded 700 years previously] to Camillus, he placed the origins of Rome in the early eleventh century BC".

- ISSN 0009-8353.

Quintus Ennius... according to his account, the founding of the city was dated about the year 900

. - ^ Koptev 2010, pp. 19–20, noting also the interpretation that Ennius' claim of "seven hundred years" having elapsed may be from the time of Camillus, which imply c. 1100 BC.

- ^ Koptev 2010, pp. 15–16, noting that this was the first estimate of Rome's foundation; Koptev also notes Dionysius' later commentary expressing bafflement as to the choice of this year.

- ^ Koptev 2010, p. 43. "600 years before the consulate of M. Aemilius Lepidus and C. Popilius, which took place in 158 BC".

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 72; Forsythe 2005, p. 94.

- OCLC 415753. See Olympiad 6.4.

- ^ Koptev 2010, p. 20. "first year of the seventh Olympiad, 751 BC".

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 401.

- ^ Koptev 2010, p. 17; Momigliano 1989, p. 82.

- ^ Drummond 1989, p. 626.

- ^ Koptev 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 72.

- ^ a b Lomas 2018, p. 50.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, pp. 94, 369–70, noting that Fabius Pictor's work did not include five fictitious years of anarchy, which extended the chronology to Varro's date. See Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom., 1.74.1.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 94; Lomas 2018, p. 50; Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom., 1.74.1.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 36–37.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 94; Lomas 2018, p. 50.

- ^ Miles 1995, pp. 138–39, on Livy, notes how he distinguishes between literal truth and a Roman "right to claim descent from Mars... because it appropriate symbolises the martial accomplishments of [later] Romans, who... have the ability to compel others to accede to that claim". Miles 1995, p. 142.

- ^ Miles 1995, p. 142.

- ^ a b Lomas 2018, p. 45.

- ^ Miles 1995, p. 147 n. 15: in Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom., 1.85.1–3, Numitor sends the twins to found a city and gives them assistance; in Livy, 1.6–7 the twins do so on their own initiative.

- ^ Miles 1995, p. 147. Remus sees birds first; Romulus sees more. The correct interpretation of the omens "is ambiguous" and "is settled only by the murder of Remus and by the success of Romulus and his city".

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 96. Forsythe notes also that some scholars, like T P Wiseman, believe the tale was an invention of the fourth century BC and reflected self-image of the then-emerging patrician and plebeian nobiles.

- ^ Miles 1995, p. 148 n. 17, noting that Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom., 1.87.2–3 "suppresses altogether" the fratricide and instead has Remus killed by an unknown assailant with Romulus mourning his death.

- ^ Miles 1995, p. 147 n. 16: in Livy, 1.8.1, 1.8.6, 2.1.4 the city is made of only refugees; in Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom., 1.85.3 it is instead made up of both refugees as well as prominent men from Alba Longa and descendants of Trojan exiles.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 97, adding that "Titus Tatius" may be a name for an early Roman monarch who was removed from the narrative of seven kings.

- ^ Cornell 1995, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Cornell 1995, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Cornell 1995, pp. 63, 413 n. 45, citing Iliad 20.307f.

- ^ Cornell 1995, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Cornell 1995, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 94. "Troy's unhistorical connection with Rome was maintained by inventing the Alban kings, whose reigns were made to span the chronological gap between Troy's destruction (1184/3 BC according to Eratosthenes) and Rome's foundation".

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 141. "In the developed legend of the origins of Rome, the son of Aeneas founded a hereditary dynasty at Alba Longa. But this Alban dynasty was an antiquarian fiction devised for chronographic reasons".

- ^ Momigliano 1989, p. 58. "Hence [from chronological difficulties] the creation of a series of intermediate Alban kings, which the poet Naevius had not yet considered necessary, but which his contemporary Fabius Pictor admitted".

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 47, citing Livy, 1.1.

- ^ a b c Lomas 2018, p. 47.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 37–38.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 38; Lomas 2018, p. 47.

- ^ Cornell 1995, pp. 37, 39. "The legendary material [Greek myths] became a coherent body of pseudo-historical tradition and was the object of intense research".

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 39, referencing also Greek claims that Persians, Indians, and Celts also were all descended from Greek gods or heroes.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 39.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 40.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 93.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 37.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 65.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Miles 1995, p. 137 instead has "at least twenty-five".

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 94.

- ^ Bickerman 1952, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Bickerman 1952, p. 67.

- ^ Bickerman 1952, p. 69.

Modern sources

- Beard, Mary (2015). SPQR: a history of ancient Rome (1st ed.). New York: Liveright Publishing. OCLC 902661394.

- Bettelli, Marco (2012-10-26). "Rome, city of: 1. Prehistoric (earliest remains)". Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley. .

- Bickerman, Elias J (1952). "Origines Gentium". Classical Philology. 47 (2): 65–81. ISSN 0009-837X.

- Cornell, Tim (1995). The beginnings of Rome. London: Routledge. OCLC 31515793.

- Forsythe, Gary (2005). A critical history of early Rome: from prehistory to the first Punic War. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 70728478.

- Koptev, Aleksandr (2010). "Timaeus of Tauromenium and Early Roman Chronology". In Deroux, Carl (ed.). Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History. Collection Latomus. Vol. 323. Brussels: Éditions Latomus. pp. 5–48. ISBN 978-2-87031-264-3.

- Lomas, Kathryn (2018). The rise of Rome: from the Iron Age to the Punic Wars (1st Harvard ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 1015274849.

- Miles, Gary B (1995). Livy: reconstructing early Rome. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. OCLC 31658236.

- Walbank, FW; et al., eds. (1989). The rise of Rome to 220 BC. Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 7 Pt. 2 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23446-8.

- Momigliano, A. "The origins of Rome". In CAH2 7.2 (1989), pp. 52–112.

- Drummond, A. "Appendix". In CAH2 7.2 (1989), pp. 625–44.

Ancient sources

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1937–50) [1st century BC]. Roman Antiquities. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Cary, Ernest. Harvard University Press – via LacusCurtius.

- Livy (1905) [1st century BC]. . Translated by Roberts, Canon – via Wikisource.