Polybius

Polybius | |

|---|---|

Anacyclosis |

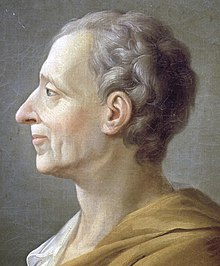

Polybius (/pəˈlɪbiəs/; Greek: Πολύβιος, Polýbios; c. 200 – c. 118 BC) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work The Histories, a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 BC, recording in detail events in Italy, Iberia, Greece, Macedonia, Syria, Egypt and Africa, and documented the Punic Wars and Macedonian Wars among many others.

Polybius's Histories is important not only for being the only Hellenistic historical work to survive in any substantial form, but also for its analysis of constitutional change and the mixed constitution. Polybius's discussion of the

The leading expert on Polybius for nearly a century was F. W. Walbank (1909–2008), who published studies related to him for 50 years, including a long commentary of his Histories and a biography.[3]

Polybius was a close friend and mentor to

Early life

Polybius was born around 200 BC in Megalopolis, Arcadia,[4] when it was an active member of the Achaean League. The town was revived, along with other Achaean states, a century before he was born.[5]

Polybius's father, Lycortas, was a prominent, land-owning politician and member of the governing class who became strategos (commanding general) of the Achaean League.[6] Consequently, Polybius was able to observe first hand during his first 30 years the political and military affairs of Megalopolis, gaining experience as a statesman.[4] In his early years, he accompanied his father while travelling as ambassador.[7] He developed an interest in horse riding and hunting, diversions that later commended him to his Roman captors.

In 182 BC, he was given the honour of carrying the funeral urn of

Personal experiences

Polybius's father, Lycortas, was a prominent advocate of neutrality during the Roman war against

When Scipio defeated the

After the destruction of Corinth in the same year, Polybius returned to Greece, making use of his Roman connections to lighten the conditions there. Polybius was charged with the difficult task of organizing the new form of government in the Greek cities, and in this office he gained great recognition.

At Rome

In the succeeding years, Polybius resided in

He later wrote about this war in a lost monograph. Polybius probably returned to Greece later in his life, as evidenced by the many existent inscriptions and statues of him there. The last event mentioned in his Histories seems to be the construction of the Via Domitia in southern France in 118 BC, which suggests the writings of Pseudo-Lucian may have some grounding in fact when they state, "[Polybius] fell from his horse while riding up from the country, fell ill as a result and died at the age of eighty-two".

The Histories

The Histories is a universal history which describes and explains the rise of the Roman Republic as a global power in the ancient Mediterranean world. The work documents in detail political and military affairs across the Hellenistic Mediterranean between 264 and 146 BC, and in its later books includes eyewitness accounts of the sack of Carthage and Corinth in 146 BC, and the Roman annexation of mainland Greece after the Achaean War.[8]

While Polybius's Histories covers the period from 264 BC to 146 BC, it mainly focuses on the years 221 BC to 146 BC, detailing Rome's rise to supremacy in the Mediterranean by overcoming their geopolitical rivals: Carthage, Macedonia, and the Seleucid empire. Books I-II are The Histories' introduction, describing events in Italy and Greece before 221/0 BC, including the

Three discursive books on politics, historiography and geography break up the historical narrative:

- In Book VI, Polybius outlines his famous theory of the "cycle of constitutions" (the anacyclosis) and describes the political, military, and moral institutions that allowed the Romans to defeat their rivals in the Mediterranean. Polybius concludes that the Romans are the pre-eminent power because they currently have customs and institutions which balance and check the negative impulses of their people and promote a deep desire for noble acts, a love of virtue, piety towards parents and elders, and a fear of the gods (deisidaimonia).

- In Book XII, Polybius discusses how to write history and criticises the historical accounts of numerous previous historians, including Timaeus for his account of the same period of history. He asserts Timaeus' point of view is inaccurate, invalid, and biased in favour of Rome. Christian Habicht considered his criticism of Timaeus to be spiteful and biased,[10] However, Polybius's Histories is also useful in analyzing the different Hellenistic versions of history and of use as a more credible illustration of events during the Hellenistic period.

- Book XXXIV discussed geographical matters and the importance of geography in a historical account and in a stateman's education. Unfortunately, this book has been almost entirely lost.

Sources

Polybius held that historians should, if possible, only chronicle events whose participants the historian was able to interview,[11] and was among the first to champion the notion of factual integrity in historical writing. In the twelfth volume of his Histories, Polybius defines the historian's job as the analysis of documentation, the review of relevant geographical information, and political experience. In Polybius's time, the profession of a historian required political experience (which aided in differentiating between fact and fiction) and familiarity with the geography surrounding one's subject matter to supply an accurate version of events.

Polybius himself exemplified these principles as he was well travelled and possessed political and military experience. He consulted and used written sources providing essential material for the period between 264 BC to 220 BC, including, for instance, treaty documents between Rome and Carthage in the First Punic War, the history of the Greek historian Phylarchus, and the Memoirs of the Achaean politician, Aratus of Sicyon. When addressing events after 220 BC, he continued to examine treaty documents, the writings of Greek and Roman historians and statesmen, eye-witness accounts and Macedonian court informants to acquire credible sources of information, although rarely did he name his sources (see, exceptionally, Theopompus).

As historian

Polybius wrote several works, most of which are lost. His earliest work was a biography of the Greek statesman Philopoemen; this work was later used as a source by Plutarch when composing his Parallel Lives; however, the original Polybian text is lost. In addition, Polybius wrote an extensive treatise entitled Tactics, which may have detailed Roman and Greek military tactics. Small parts of this work may survive in his major Histories, but the work itself is lost as well. Another missing work was a historical monograph on the events of the Numantine War. The largest Polybian work was, of course, his Histories, of which only the first five books survive entirely intact, along with a large portion of the sixth book and fragments of the rest. Along with Cato the Elder (234–149 BC), he can be considered one of the founding fathers of Roman historiography.

Livy made reference to and uses Polybius's Histories as source material in his own narrative. Polybius was among the first historians to attempt to present history as a sequence of causes and effects, based upon a careful examination and criticism of tradition. He narrated his history based upon first-hand knowledge. The Histories capture the varied elements of the story of human behavior: nationalism, xenophobia, duplicitous politics, war, brutality, loyalty, valour, intelligence, reason and resourcefulness.

Aside from the narrative of the historical events, Polybius also included three books of digressions. Book 34 was entirely devoted to questions of geography and included some trenchant criticisms of

A key theme of The Histories is good leadership, and Polybius dedicates considerable time to outlining how the good statesman should be rational, knowledgeable, virtuous and composed. The character of the Polybian statesman is exemplified in that of Philip II, who Polybius believed exhibited both excellent military prowess and skill, as well as proficient ability in diplomacy and moral leadership.[12] His beliefs about Philip's character led Polybius to reject the historian Theopompus' description of Philip's private, drunken debauchery. For Polybius, it was inconceivable that such an able and effective statesman could have had an immoral and unrestrained private life as described by Theopompus.[13] The consequences of bad leadership are also highlighted throughout the Histories. Polybius saw, for instance, the character and leadership of the later Philip V of Macedon, one of Rome's leading adversaries in the Greek East, as the opposite of his earlier exemplary namesake. Philip V became increasingly tyrannical, irrational and impious following brilliant military and political success in his youth; this resulted, Polybius believed, in his abandonment by his Greek allies and his eventual defeat by Rome in 197 BC.[14]

Other important themes running throughout The Histories include the role of Fortune in the affairs of nations, how a leader might weather bravely these changes of fortune with dignity,[15] the educational value of history and how it should demonstrate cause and effect (or apodeiktike) to provide lessons for statesmen, and that historians should be "men of action" to gain appropriate experience so as to understand how political and military affairs are likely to pan out (pragmatikoi).

Polybius is considered by some to be the successor of

It has long been acknowledged that Polybius's writings are prone to a certain

As a hostage in Rome, then as client to the Scipios, and after 146 BC, a collaborator with Roman rule, Polybius was probably in no position to freely express any negative opinions of Rome.

Cryptography

Polybius was responsible for a useful tool in

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | B | C | D | E |

| 2 | F | G | H | I/J | K |

| 3 | L | M | N | O | P |

| 4 | Q | R | S | T | U |

| 5 | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | B | Γ | Δ | E |

| 2 | Z | H | Θ | I | K |

| 3 | Λ | M | N | Ξ | O |

| 4 | Π | P | Σ | T | Y |

| 5 | Φ | X | Ψ | Ω |

In the Polybius square, letters of the alphabet were arranged left to right, top to bottom in a 5 × 5 square. When used with the 26-letter Latin alphabet two letters, usually I and J, are combined. When used with the Greek alphabet, which has exactly one fewer letters than there are spaces (or code points) in the square, the final "5,5" code point encodes the spaces in between words. Alternatively, it can denote the end of a sentence or paragraph when writing in continuous script.

Five numbers are then aligned on the outside top of the square, and five numbers on the left side of the square vertically. Usually these numbers were arranged 1 through 5. By cross-referencing the two numbers along the grid of the square, a letter could be deduced.

In The Histories, Polybius specifies how this cypher could be used in fire signals, where long-range messages could be sent by means of torches raised and lowered to signify the column and row of each letter. This was a great leap forward from previous fire signaling, which could send prearranged codes only (such as, 'if we light the fire, it means that the enemy has arrived').

Other writings of

Influence

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Polybius was considered a poor stylist by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, writing of Polybius's history that "no one has the endurance to reach [its] end".[23] Nevertheless, clearly he was widely read by Romans and Greeks alike. He is quoted extensively by Strabo writing in the 1st century BC and Athenaeus in the 3rd century AD.

His emphasis on explaining causes of events, rather than just recounting events, influenced the historian Sempronius Asellio. Polybius is mentioned by Cicero and mined for information by Diodorus, Livy, Plutarch and Arrian. Much of the text that survives today from the later books of The Histories was preserved in Byzantine anthologies.

His works reappeared in the West first in Renaissance Florence. Polybius gained a following in Italy, and although poor Latin translations hampered proper scholarship on his works, they contributed to the city's historical and political discourse. Niccolò Machiavelli in his Discourses on Livy evinces familiarity with Polybius. Vernacular translations in French, German, Italian and English first appeared during the 16th century.[24] Consequently, in the late 16th century, Polybius's works found a greater reading audience among the learned public. Study of the correspondence of such men as Isaac Casaubon, Jacques Auguste de Thou, William Camden and Paolo Sarpi reveals a growing interest in Polybius's works and thought during the period. Despite the existence of both printed editions in the vernacular and increased scholarly interest, however, Polybius remained an "historian's historian", not much read by the public at large.[25]

Printings of his work in the vernacular remained few in number—seven in French, five in English (John Dryden provided an enthusiastic preface to Sir Henry Sheers' edition of 1693) and five in Italian.[26] Polybius's political analysis has influenced republican thinkers from

According to Edward Tufte, he was also a major source for Charles Joseph Minard's figurative map of Hannibal's overland journey into Italy during the Second Punic War.[28]

In his Meditations On Hunting, Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset calls Polybius "one of the few great minds that the turbid human species has managed to produce", and says the damage to the Histories is "without question one of the gravest losses that we have suffered in our Greco-Roman heritage".

The Italian version of his name, Polibio, was used as a male first name—for example, the composer Polibio Fumagalli—though it never became very common.

The University of Pennsylvania has an intellectual society, the Polybian Society, which is named in his honor and serves as a non-partisan forum for discussing societal issues and policy.

Editions and translations

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Usher, S. (ed. and trans.) Critical Essays, Volume II. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Polybii Historiae, editionem a Ludovico Dindorfi curatam, retractavit Theodorus Büttner-Wobst, Lipsiae in aedibus B. G. Teubneri, vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 4, vol. 5, 1882–1904.

- Polybius (1922–1927). Polybius: The Histories. The Loeb Classical Library (in Ancient Greek, English, and Latin). Translated by Paton, W.R. London; New York: William Heinemann; G.P. Putnam's Sone.

- —— (1922A). Polybius. Vol. I. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99142-7. Loeb Number L128; Books I-II.

- —— (1922B). Polybius. Vol. II. ISBN 0-674-99152-4. Loeb Number L137; Books III-IV.

- —— (1923). Polybius. Vol. III. ISBN 0-674-99153-2. Loeb Number L138; Books V-VIII.

- —— (1925). Polybius. Vol. IV. ISBN 0-674-99175-3. Loeb Number L159; Books IX-XV.

- —— (1926). Polybius. Vol. V. ISBN 0-674-99176-1. Loeb Number L160; Books XVI-XXVII.

- —— (1927). Polybius. Vol. VI. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99178-8. Loeb Number L161; Books XXVIII-XXXIX.

- —— (1922A). Polybius. Vol. I. Harvard University Press.

- Polybius (2012). Polybius: The Histories. The Loeb Classical Library (in Ancient Greek, English, and Latin). Translated by Paton, W.R. Chicago: University of Chicago (LacusCurtius).

- The Histories or The Rise of the Roman Empire by Polybius:

- At Perseus Project: English & Greek version

- At

- At "LacusCurtius": Short introduction to the life and work of Polybius

- 1670 edition of Polybius's works vol.1 at the Internet archive

- 1670 edition of Polybius's works vol.2 at the Internet archive

- Polybius: "The Rise Of The Roman Empire", Penguin, 1979.

- "Books 1–5 of History. Ethiopian Story. Book 8: From the Departure of the Divine Marcus" featuring Book I-V of The Histories, digitized, from the World Digital Library

See also

- Anacyclosis

- Kyklos

- Polybius square

- Mixed government

Notes and references

- ISBN 978-0-19-966891-5, pp 281-282.

- ^ "Polybius and the Founding Fathers: The separation of powers".

- ^ Gibson & Harrison: Polybius, pp. 1–5.

- ^ ISBN 9781107630604.

- ISBN 9780141393582.

- ^ "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 39, chapter 35". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-02.

- ^ ISBN 9781441111357.

- ^ Polybius (~150 B.C.). The Rise of the Roman Republic. Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert (1979). Penguin Books. London, England.

- ISBN 9780192866769., pp. 3, 34-58, 107-118

- ^ Athens from Alexander to Antony by Christian Habicht p119

- ^ Farrington, Scott Thomas (February 2015). "A Likely Story: Rhetoric and the Determination of Truth in Polybius's Histories." Histos 9: 29-66. (p. 40): "Polybius begins his history proper with the 140th Olympiad because accounts of the remote past amount to hearsay and do not allow for safe judgements (διαλήψεις) and assertions (ἀποφάσεις) regarding the course of events.... he can relate events he saw himself, or he can use the testimony of eyewitnesses. ([footnote 34:] Pol. 4.2.2: ἐξ οὗ συµβαίνει τοῖς µὲν αὐτοὺς ἡµᾶς παραγεγονέναι, τὰ δὲ παρὰ τῶν ἑωρακότων ἀκηκοέναι.)" [archive URLs: 1 (full text), 2 (abstract & journal citation)]

- ISBN 9780192866769., pp. 291-295

- ^ Plb. 8.9.3-4

- ISBN 9780192866769., pp. 59-100, 184-227

- ^ Plb. 1.1.1-2

- ^ Peter Green, Alexander to Actium

- ^ Ronald J. Mellor, The Historians of Ancient Rome

- ^ H. Ormerod, Piracy in the Ancient World, p.141

- ISBN 87-7304-267-6

- ^ Robert Pashley, Travels in Crete, 1837, J. Murray

- ^ "C. Michael Hogan, Cydonia, Modern Antiquarian, January 23, 2008". Themodernantiquarian.com. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ Comp. 4

- ISBN 0-14-044362-2.

- JSTOR 2504511.

- JSTOR 2504511.

- ^ Marshall Davies Lloyd, Polybius and the Founding Fathers: the separation of powers, Sept. 22, 1998.

- ^ "Minard's figurative map of Hannibal's war". Edwardtufte.com. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

Sources

Ancient sources

- Titus Livius of Patavium (Livy), libri XXI — XLV

- Pseudo-Lucian Makrobioi

- Paulus Orosius libri VII of Histories against Pagans

Modern sources

- Champion, Craige B. (2004) Cultural Politics in Polybius's Histories. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Davidson, James: 'Polybius' in Feldherr, Andrew ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Historians (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

- Derow, Peter S. 1979. "Polybius, Rome, and the East." Journal of Roman Studies 69:1–15.

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (1995) Moral Vision in the Histories of Polybius. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Farrington, Scott Thomas. 2015. "A Likely Story: Rhetoric and the Determination of Truth in Polybius' Histories. Histos: The On-Line Journal of Ancient Historiography 9: 29–66.

- Gibson, Bruce & Harrison, Thomas (editors): Polybius and his World: Essays in Memory of F.W. Walbank, (Oxford, 2013).

- McGing, Brian C. (2010) Polybius: The Histories. Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Momigliano, Arnaldo M.: Sesto Contributo alla Storia degli Studi Classici e del Mondo Antico (Rome, 1980).

- —— Vol. V (1974) "The Historian's Skin", 77–88 (Momigliano Bibliography no. 531)

- —— Vol. VI (1973) "Polibio, Posidonio e l'imperialismo Romano", 89 (Momigliano Bibliography no. 525) (original publication: Atti della Accademia delle Scienze di Torino, 107, 1972–73, 693–707).

- Moore, John M (1965) The Manuscript Tradition of Polybius (Cambridge University Press).

- Moore, Daniel Walker (2020) Polybius: Experience and the Lessons of History (Brill, Leiden).

- Nicholson, Emma (2022). "Polybius (1), Greek historian, c. 200–c. 118 BCE". Oxford Classical Dictionary. ISBN 9780199381135.

- Nicholson, Emma (2023). Philip V of Macedon in Polybius' Histories: Politics, History, and Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199381135.

- Pausch, Dennis (2014) "Livy Reading Polybius: Adapting Greek Narrative to Roman History." In Defining Greek Narrative. Edited by Douglas L. Cairns & Ruth Scodel, 279–297. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Sacks, Kenneth S. (1981) Polybius on the Writing of History. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Schepens, Guido, and Jan Bollansée, eds. 2005. The Shadow of Polybius: Intertextuality as a Research Tool in Greek Historiography. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters.

- Walbank, Frank W.:

- —— Philip V of Macedon, the Hare Prize Essay 1939 (Cambridge University Press, 1940)

- —— A Historical Commentary on Polybius (Oxford University Press)

- Vol. I (1957) Commentary on Books I–VI

- Vol. II (1967) Commentary on Books VII–XVIII

- Vol. III (1979) Commentary on Books XIX–XL

- —— (1972) Polybius (University of California Press).

- ___ (2002) Polybius, Rome and the Hellenistic World: Essays and Reflections (Cambridge University Press).

External links

Quotations related to Polybius at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Polybius at Wikiquote Works by or about Polybius at Wikisource

Works by or about Polybius at Wikisource- Works by Polybius at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Polybius at Perseus Digital Library

- Works by or about Polybius at Internet Archive