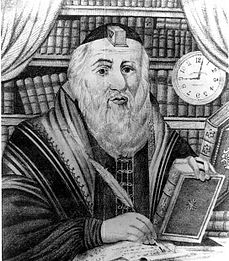

Vilna Gaon

Yahrtzeit | 19 Tishrei | |

|---|---|---|

| Buried | Vilnius, Lithuania | |

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman,

Through his annotations and emendations of Talmudic and other texts, he became one of the most familiar and influential figures in rabbinic study since the Middle Ages. Although he is chronologically one of the Acharonim, some considered him one of the Rishonim[7][8][9]

Large groups of people, including many

Born in Sielec in the

When Hasidic Judaism became influential in his native town, the Vilna Gaon joined the "opposers" or Misnagdim, rabbis and heads of the Polish communities, to curb Hasidic influence.[citation needed]

While he advocated studying branches of secular education such as Mathematics in order to better understand rabbinic texts, he harshly condemned the study of Philosophy and Metaphysics.[10][11]

Youth and education

The Vilna Gaon was born in

According to legend he had committed the

Later he decided to go into "exile" and he wandered in various parts of Europe including Poland and Germany.[12] By the time he was twenty years old, rabbis were submitting their most difficult halakhic problems to him. He returned to his native city in 1748, having by then acquired considerable renown.[13]

Methods of study

The Gaon applied rigorous philological methods to the Talmud and rabbinic literature, making an attempt toward a critical examination of the text.

He devoted much time to the

Antagonism to Hasidism

When

In 1781, when the Hasidim renewed their proselytizing work under the leadership of their Rabbi

Other work

Except for the conflict with the Hasidim, the Vilna Gaon rarely engaged in public affairs and, so far as is known, did not preside over any school in

He laid special stress on the study of the

Asceticism

The Vilna Gaon led an

The Gaon once started on a trip to the Land of Israel, but for unknown reasons did not get beyond Germany. (In the early nineteenth century, three groups of his students, known as Perushim, under the leadership of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Shklov, made their way to what was then Ottoman Palestine, settling first in Safed and later also in Jerusalem).[17] While at Königsberg he wrote to his family a famous letter that was published under the title Alim li-Terufah, Minsk, 1836.

Works

The Vilna Gaon was a copious annotator, producing many marginal glosses, notes, and brief commentaries, which were mostly dictated to his pupils. Many maintain that it was his disciples who recorded his comments, if not his editorial notes. However, nothing of his was published in his lifetime. The "Gra" was very precise in the wording of his commentaries, because he maintained that he was obligated by Torah Law that only the "

He was well versed in the mathematical works of Euclid (4th century BC) and encouraged his pupil Rabbi Baruch Schick of Shklov to translate these works into Hebrew. The Gaon is said to have written a concise mathematical work called Ayil Meshulash, which was an introductory primer to basic mathematics.[14][18][19]

Influence

He was one of the most influential rabbinic authorities since the Middle Ages, and—although he is properly an Acharon—many later authorities hold him as possessing halachic authority in the same class as the Rishonim (rabbinic authorities of the Middle Ages).

His main student Rabbi

Somewhat ironically, viewed from a traditional light, the leaders of the Haskalah movement used the study methods of the Vilna Gaon to gain adherents to their movement. Maskilim valued and adapted his emphasis on peshat over pilpul, his engagement with and mastery of Hebrew grammar and Bible, and his interest in textual criticism of rabbinic texts, further developing the philosophy of their movement.

As for the Vilna Gaon's own community, in accordance with the Vilna Gaon's wishes, three groups of his disciples and their families, numbering over 500, made

The impact of the Perushim is still apparent today in the religious practices of the Israeli Jewish community, even among non-Ashkenazim. For example, the institution of the priestly blessing by the Kohanim known as

There is a statue of the Vilna Gaon and a street named after him in Vilnius, the place of both his birth and his death. Lithuania's parliament declared 2020 as the year of the Vilna Gaon and Lithuanian Jewish History.[21] In his honour, the Bank of Lithuania issued a limited-edition silver commemorative 10-euro coin in October 2020; this is the first euro coin with Hebrew letters.[22][23]

The Vilna Gaon's brother Avraham authored the revered work "Maalot Hatorah". His son Abraham was also a scholar of note.

Death

The Vilna Gaon died in 1797, aged 77, and was subsequently buried in the Šnipiškės cemetery in Vilnius, now in

In the 1950s, Soviet authorities planned to build a stadium and concert hall on the site. They allowed the remains of the Vilna Gaon to be removed and re-interred at the new cemetery.[24]

See also

- Hasidim and Misnagdim

- Lithuanian Jews

- Perushim

- Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum

References

- ^ Within recent decades he has been given the surname Kremer. However neither the Vilna Gaon nor his descendants apparently used this surname, which means shopkeeper. It was possibly mistakenly derived from a nickname of his ancestor Rabbi Moshe Kremer. "The Vilna Gaon, part 3 (Review of Eliyahu Stern, The Genius)". Marc B. Shapiro

- Bar Ilan University. Archived from the originalon March 23, 2017. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1pnj2v.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85244-259-3.

- ISBN 978-1-58979-729-1.

- ^ The Threefold step of Academia Europeana: a case of Universitas Vilnensis, 2009, p. 24

- ^ Karelitz, Avraham Yeshaya. קובץ איגרות חזון איש [Collected letters of the 'Chazon Ish'] (in Hebrew). pp. Part one, section 32.

אנו מתייחסים להגר"א בשורה של משה רבנו, עזרא, רבנו הקדוש, רב אשי והרמב"ם. הגר"א שנתגלה תורה על ידו כקדוש מעותד לכך שהאיר במה שלא הואר עד שבא ונטל חלקו, והוא נחשב אחד מהראשונים,

- ^ Danzig, Abraham. זכרו תורת משה (in Hebrew). p. 31.

רבי אליהו חסיד, הוא היה עיר וקדיש כאחד מן הראשונים

- ^ Tzuzmir, Yekuseil A.Z.H (1882). שו"ת מהריא"ז ענזיל (in Hebrew). Lvov. pp. 40b.

ומהר"א מווילנא אשר כחו כאחד הראשונים

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ISBN 978-0-231-13488-0.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 179:6". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Green, David B. (October 9, 2012). "This Day in Jewish History 1797: The Vilna Gaon Dies". Haaretz. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Schechter, Solomon; Seligsohn, M. "ELIJAH BEN SOLOMON (also called Elijah Wilna, Elijah Gaon, and Der Wilner Gaon)". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Stern, Eliyahu. "The Making of Modern Judaism: Interview with Eliyahu Stern". YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

- ISBN 9780873340984.

- ^ a b Diamond, Robin (July 14, 2020). "Rabbi Mendel Kessin: End of the American Exile". blogs.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ "The Vilna Gaon". National Library of Israel.

- ^

Matthews, Michael R. (2014). International Handbook of Research in History, Philosophy and Science Teaching. Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-7654-8.

- ^

Bollag, Shimon (2007). "Mathematics". In Skolnik, Fred (ed.). Encyclopaedia Judaica: Lif-Mek (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA in association with the Keter Pub. House. p. 676. ISBN 978-0-02-865941-1.

- ^ Morgenstern, Arie. Hastening Redemption.

- ^ Nutarimas Dėl Vilniaus Gaono Ir Lietuvos Žydų Istorijos Metų Minėjimo 2020 Metais Plano Patvirtinimo

- ^ Liphshiz, Cnaan (October 24, 2020). "Lithuania mints first-ever EU coin with Hebrew letters, honoring Vilnius scholar". The Times of Israel. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Bank of Lithuania issues a silver coin dedicated to a famous Sage—the Vilna Gaon". Lietuvos bankas. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ "Jews protest to Lithuania over ancient cemetery". Reuters. August 22, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

Sources

- Etkes, Immanuel, et al. The Gaon of Vilna: the man and his image (University of California Press, 2002) ISBN 0-520-22394-2

- "The Gaon of Vilna and the Haskalah movement", by Emanuel Etkes, reprinted in Dan, Joseph (ed.). Studies in Jewish thought (Praeger, NY, 1989) ISBN 0-275-93038-6

- "The mystical experiences of the Gaon of Vilna", in Jacobs, Louis (ed.). Jewish mystical testimonies (Schocken Books, NY, 1977) ISBN 0-8052-3641-4

- Landau, Betzalel and Rosenblum, Yonason. The Vilna Gaon: the life and teachings of Rabbi Eliyahu, the Gaon of Vilna (Mesorah Pub., Ltd., 1994) ISBN 0-89906-441-8

- ISBN 1-56062-278-4

- Ackerman, C. D. (trans.) Even Sheleimah: the Vilna Gaon looks at life (Targum Press, 1994) ISBN 0-944070-96-5

- Schapiro, Moshe. Journey of the Soul: The Vilna Gaon on Yonah/Johan: an allegorical commentary adapted from the Vilna Gaon's Aderes Eliyahu (Mesorah Pub., Ltd., 1997). ISBN 1-57819-161-0

- Freedman, Chaim. Eliyahu's Branches: The Descendants of the Vilna Gaon (Of Blessed and Saintly Memory) and His Family (Avotaynu, 1997) ISBN 1-886223-06-8

- Rosenstein, Neil. The Gaon of Vilna and his Cousinhood (Center for Jewish Genealogy, 1997) ISBN 0-9610578-5-8

External links

- Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) entry for "ELIJAH BEN SOLOMON (also called Elijah Wilna, Elijah Gaon, and Der Wilner Gaon): (Redirected from ELIJAH GAON.)," by Solomon Schechter and M. Seligsohn

- Encyclopaedia Judaica (2007 - 2nd edition) entry for "Elijah Ben Solomon Zalman"," by Israel Klausner, Samuel Mirsky, David Derovan, and Menahem Kaddari

- A Precious Legacy Works of the Vilner Gaon Eliyahu b. Zalman

- Biography from the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum