Lithuania

Republic of Lithuania Lietuvos Respublika (Lithuanian) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Anthem: Ethnic groups (2024[2])

| ||

| Religion (2021[3] ) |

| |

| Demonym(s) | Lithuanian | |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[4][5][6][7] | |

| Gitanas Nausėda | ||

| Gintautas Paluckas | ||

| Saulius Skvernelis | ||

| Legislature | Seimas | |

| Formation | ||

| 9 March 1009 | ||

| 1236 | ||

• Coronation of Mindaugas | 6 July 1253 | |

| 2 February 1386 | ||

• Commonwealth created | 1 July 1569 | |

| 24 October 1795 | ||

| 16 February 1918 | ||

| 16 June 1940 | ||

| 11 March 1990 | ||

| Area | ||

• Total | 65,300[8] km2 (25,200 sq mi) (121st) | |

• Water (%) | 1.98 (2015)[9] | |

| Population | ||

• 2025 estimate | ||

• Density | 44/km2 (114.0/sq mi) (138th) | |

| GDP (PPP) | 2025 estimate | |

• Total | ||

• Per capita | ||

| GDP (nominal) | 2025 estimate | |

• Total | ||

• Per capita | ||

| Gini (2023) | medium inequality | |

| HDI (2022) | very high (37th) | |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) | |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) | |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Date format | yyyy-mm-dd[a][14][15] | |

| Calling code | +370 | |

| ISO 3166 code | LT | |

| Internet TLD | .lt | |

Lithuania,

For millennia, the southeastern shores of the Baltic Sea were inhabited by various Baltic tribes. In the 1230s, Lithuanian lands were united for the first time by Mindaugas, who formed the Kingdom of Lithuania on 6 July 1253. Subsequent expansion and consolidation resulted in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which by the 14th century was the largest country in Europe. In 1386, the Grand Duchy entered into a de facto personal union with the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. The two realms were united into the bi-confederal Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569, forming one of the largest and most prosperous states in Europe. The Commonwealth lasted more than two centuries, until neighbouring countries gradually dismantled it between 1772 and 1795, with the Russian Empire annexing most of Lithuania's territory.

Towards the end of

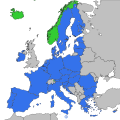

Lithuania is a developed country with a high income and an advanced economy. Lithuania is a member of the European Union, the Council of Europe, the eurozone, the Nordic Investment Bank, the Schengen Agreement, NATO, and OECD. It also participates in the Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB8) regional co-operation format.

Etymology

The spelling of Lithuania was a later addition to the original Latinate Lituania since 1800 as a form of

Artūras Dubonis proposed another hypothesis,

History

Early history and Baltic tribes

The history of Lithuania dates back to settlements founded about 10,000 years ago.

From the 9th to the 11th centuries, coastal Balts were subjected to raids by the Vikings.[40] Lithuania comprised mainly the culturally different regions of Samogitia (known for its early medieval skeletal burials), and further east Aukštaitija, or Lithuania proper (known for its early medieval cremation burials). The area was remote and unattractive to outsiders, including traders, which accounts for its separate linguistic, cultural and religious identity and delayed integration into general European patterns and trends.[41] Traditional Lithuanian pagan customs and mythology, with many archaic elements, were long preserved. Rulers' bodies were cremated up until the conversion to Christianity: the descriptions of the cremation ceremonies of the grand dukes Algirdas and Kęstutis have survived.[42]

Kingdom of Lithuania, Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The first written record of the name for the country dates back to 1009 AD.

From the late 13th century members of the

In the 15th century the strengthened

The mid-17th century was marked with disastrous military loses for Lithuania as during the

In the second half of the 18th century the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was three times

Efforts to restore statehood

Following the annexation the Russian Tsarist authorities implemented Russification policies in Lithuania, which then made a part of a new administrative region Northwestern Krai.[61] In 1812 Napoleon during the French invasion of Russia has established the puppet Lithuanian Provisional Governing Commission to support his war efforts, however after Napoleon's defeat the Russian rule was reinstated in Lithuania.[61]

During the November Uprising (1830–1831) the Lithuanians and Poles jointly attempted to restore their statehoods, however the Russian victory resulted in stricter Russification measures: the Russian language was introduced in all government institutions, Vilnius University was closed in 1832, and theories that Lithuania had been a "Western Russian" state since its establishment were propagated.[61] Subsequently, the Lithuanians once again tried to restore statehood by participating in the January Uprising (1863–1864), but yet another Russian victory resulted in even stronger Russification policies with the introduction of the Lithuanian press ban, pressure on the Catholic Church in Lithuania and Mikhail Muravyov-Vilensky's repressions.[61][62]

Simonas Daukantas promoted a return to Lithuania's pre-Commonwealth traditions, which he depicted as a Golden Age of Lithuania and a renewal of the native culture, based on the Lithuanian language and customs. With those ideas in mind, he wrote already in 1822 a history of Lithuania in Lithuanian – Darbai senųjų lietuvių ir žemaičių (The Deeds of Ancient Lithuanians and Samogitians), though it was not published at that time.[63] A colleague of S. Daukantas, Teodor Narbutt, wrote in Polish a voluminous Ancient History of the Lithuanian Nation (1835–1841), where he likewise expounded and expanded further on the concept of historic Lithuania, whose days of glory had ended with the Union of Lublin in 1569. Narbutt, invoking German scholarship, pointed out the relationship between the Lithuanian and Sanskrit languages.[64]

The Lithuanians resisted Russification through an extensive network of Lithuanian book smugglers, secret Lithuanian publishing and homeschooling.[65] Moreover, the Lithuanian National Revival, inspired by Lithuanian history, language and culture, laid the foundations for the reestablishment of an independent Lithuania.[66] The Great Seimas of Vilnius was held in 1905 and its participants adopted resolutions which demanded a wide autonomy for Lithuania.[61]

Restored statehood and occupations

During World War I the German Empire annexed Lithuanian territories from the Russian Empire and they became a part of Ober Ost.[67] In 1917, the Lithuanians organized the Vilnius Conference which adopted a resolution, featuring the aspiration for the restoration of Lithuania's sovereignty and military alliance with Germany and elected the Council of Lithuania.[67] In 1918, the short-lived Kingdom of Lithuania was proclaimed; however on 16 February 1918 the Council of Lithuania adopted the Act of Independence of Lithuania which restored Lithuania as a democratic republic with its capital in Vilnius and without any political ties that existed with other nations in the past.[67] In 1918–1920 the Lithuanians defended the statehood of Lithuania during the Lithuanian Wars of Independence with Bolsheviks, Bermontians and Poles.[67] The aims of the newly restored Lithuania clashed with Józef Piłsudski's plans to create a federation (Intermarium) in territories previously ruled by the Jagiellonians.[68] The Lithuanian authorities prevented the 1919 Polish coup attempt in Lithuania and in 1920 during the Żeligowski's Mutiny the Polish forces captured Vilnius Region and established a puppet state of the Republic of Central Lithuania, which in 1922 was incorporated into Poland.[67] Consequently, Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania where the Constituent Assembly of Lithuania was held and other primary Lithuanian institutions operated until 1940.[69] In 1923, the Klaipėda Revolt was organized which unified the Klaipėda Region with Lithuania.[70] The 1926 Lithuanian coup d'état replaced the democratically elected government and president with an authoritarian regime led by Antanas Smetona.[70]

In the late 1930s Lithuania accepted the 1938 Polish ultimatum, 1939 German ultimatum and transferred the Klaipėda Region to Nazi Germany and following the beginning of the World War II concluded the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty.[71] In 1940 Lithuania accepted the Soviet ultimatum and recovered the control of its historical capital Vilnius, however, the acceptance resulted in the Soviet occupation of Lithuania and its transformation into the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic.[71] In 1941 during the June Uprising in Lithuania it was attempted to restore independent Lithuania and the Red Army was expelled from its territory, however in a few days Lithuania was occupied by Nazi Germany.[71] In 1944 Lithuania was re-occupied by the Soviet Union and Soviet political repressions along with Soviet deportations from Lithuania resumed.[71] Thousands of Lithuanian partisans and their supporters attempted to militarily restore independent Lithuania, but their resistance was eventually suppressed in 1953 by the Soviet authorities and their collaborators.[71] Jonas Žemaitis, the chairman of the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters, was captured and executed in 1954, his successor as chairman Adolfas Ramanauskas was brutally tortured and executed in 1957.[72][73] Since the late 1980s Sąjūdis movement sought for the restoration of independent Lithuania and in 1989 the Baltic Way was held.[71]

1990–present

On 11 March 1990, the Supreme Council announced the restoration of Lithuania's independence. Lithuania became the first Soviet-occupied state to announce the restitution of independence.[75] On 20 April 1990, the Soviets imposed an economic blockade by ceasing to deliver supplies of raw materials to Lithuania.[76] Not only domestic industry, but also the population started feeling the lack of fuel, essential goods, and even hot water. Although the blockade lasted for 74 days, Lithuania did not renounce the declaration of independence.[77]

Gradually, economic relations were restored. However, tensions peaked again in January 1991. Attempts were made to carry out a coup using the

On 25 October 1992, citizens voted in a referendum to adopt the current constitution.[77] On 14 February 1993, during the direct general elections, Algirdas Brazauskas became the first president after the restoration of independence.[77] On 31 August 1993 the last units of the former Soviet Army left Lithuania.[81]

On 31 May 2001, Lithuania joined the World Trade Organization (WTO).[82] Since March 2004, Lithuania has been part of NATO.[83] On 1 May 2004, it became a full member of the European Union,[84] and a member of the Schengen Agreement in December 2007.[85] On 1 January 2015, Lithuania joined the eurozone and adopted the European Union's single currency.[86] On 4 July 2018, Lithuania officially joined the OECD.[87] Dalia Grybauskaitė was the first female President of Lithuania (2009–2019) and the first to be re-elected for a second consecutive term.[88] On 24 February 2022, Lithuania declared a state of emergency in response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[89] Together with seven other NATO member states, it invoked NATO Article 4 to hold consultations on security.[90] On 11–12 July 2023, the 2023 NATO summit was held in Vilnius.[91]

Geography

Lithuania is located in the Baltic region of

Lithuania lies at the edge of the

After a re-estimation of the boundaries of the

Climate

Lithuania has a temperate climate with both

Average temperatures on the coast are −2.5 °C (27.5 °F) in January and 16 °C (61 °F) in July. In Vilnius, the average temperatures are −6 °C (21 °F) in January and 17 °C (63 °F) in July. During the summer, 20 °C (68 °F) is common during the day, while 14 °C (57 °F) is common at night; in the past, temperatures have reached as high as 30 or 35 °C (86 or 95 °F). Some winters can be very cold. −20 °C (−4 °F) occurs almost every winter. Winter extremes are −34 °C (−29 °F) in coastal areas and −43 °C (−45 °F) in the east of Lithuania.

The average annual precipitation is 800 mm (31.5 in) on the coast, 900 mm (35.4 in) in the Samogitia highlands, and 600 mm (23.6 in) in the eastern part of the country. Snow occurs every year, and it can snow from October to April. In some years, sleet can fall in September or May. The growing season lasts 202 days in the western part of the country and 169 days in the eastern part. Severe storms are rare in the eastern part of Lithuania but common in the coastal areas.

The longest records of measured temperature in the Baltic area cover about 250 years. The data show warm periods during the latter half of the 18th century, and that the 19th century was a relatively cool period. An early 20th-century warming culminated in the 1930s, followed by a smaller cooling that lasted until the 1960s. A warming trend has persisted since then.[94]

Lithuania experienced a drought in 2002, causing forest and peat bog fires.[95]

Biodiversity and conservation

After the restoration of Lithuania's independence in 1990, the Aplinkos apsaugos įstatymas (Environmental Protection Act) was adopted already in 1992. The law provided the foundations for regulating social relations in the field of environmental protection, established the basic rights and obligations of legal and natural persons in preserving the biodiversity inherent in Lithuania, ecological systems and the landscape.

Lithuania does not have high mountains and its landscape is dominated by blooming meadows, dense forests and fertile fields of cereals. However, it stands out by the abundance of

Forest has long been one of the most important natural resources in Lithuania. Forests occupy one-third of the country's territory and timber-related industrial production accounts for almost 11% of industrial production in the country.[102] Lithuania has five national parks,[103] 30 regional parks,[104] 402 nature reserves,[105] 6 strict nature reserves,[106] 668 state-protected natural heritage objects.[107]

Lithuanian ecosystems include natural and semi-natural (forests,

Agricultural land comprises 54% of Lithuania's territory (roughly 70% of that is arable land and 30% meadows and pastures), approximately 400,000 ha of agricultural land is not farmed, and acts as an ecological niche for weeds and invasive plant species. Habitat deterioration is occurring in regions with very productive and expensive lands as crop areas are expanded. Currently, 18.9% of all plant species, including 1.87% of all known fungi species and 31% of all known species of lichens, are listed in the

The wildlife populations have rebounded as the hunting became more restricted and urbanization allowed replanting forests (forests already tripled in size since their lows). Currently, Lithuania has approximately 250,000 larger wild animals or 5 per each square kilometre. The most prolific large wild animal in every part of Lithuania is the

Government and politics

Government

Since Lithuania declared the restoration of its independence on 11 March 1990, it has maintained strong democratic traditions. It held its first independent general elections on 25 October 1992, in which 56.75% of voters supported the

The Lithuanian head of state is the president, directly elected for a five-year term and serving a maximum of two terms. The president oversees foreign affairs and national security, and is the commander-in-chief of the military.[113] The president also appoints the prime minister and, on the latter's nomination, the rest of the cabinet, as well as a number of other top civil servants and the judges for all courts except the Constitutional Court.[113] The current Lithuanian head of state, Gitanas Nausėda was elected on 26 May 2019 by winning in all the municipalities of Lithuania in the second election round.[114] He was re-elected in 2024, winning more than 74% of the run-off votes.[115]

The judges of the

Political parties and elections

Lithuania was one of the first countries in the world to grant women a right to vote in the elections. Lithuanian women were allowed to vote by the 1918 Constitution of Lithuania and used their newly granted right for the first time in 1919. By doing so, Lithuania allowed it earlier than such democratic countries as the United States (1920), France (1945), Greece (1952), Switzerland (1971).[117]

Lithuania exhibits a fragmented multi-party system,[118] with a number of small parties in which coalition governments are common. Ordinary elections to the Seimas take place on the second Sunday of October every four years.[116] To be eligible for election, candidates must be at least 21 years old on the election day, not under allegiance to a foreign state and permanently reside in Lithuania.[119] Persons serving or due to serve a sentence imposed by the court 65 days before the election are not eligible. Also, judges, citizens performing military service, and servicemen of professional military service and officials of statutory institutions and establishments may not stand for election.[120] Social Democratic Party of Lithuania won the 2024 Lithuanian parliamentary elections and gained 52 of 141 seats in the parliament.[121] In November 2024, Gintautas Paluckas was confirmed as the prime minister after the Social Democrats reached a coalition agreement with Union of Democrats "For Lithuania" and Dawn of Nemunas.[122]

The President of Lithuania is the head of state of the country, elected to a five-year term in a majority vote. Elections take place on the last Sunday no more than two months before the end of current presidential term.[123] To be eligible for election, candidates must be at least 40 years old on the election day and reside in Lithuania for at least three years, in addition to satisfying the eligibility criteria for a member of the parliament. Same President may serve for not more than two terms.[124] Gitanas Nausėda was elected as an independent candidate in 2019 and re-elected in 2024.[125]

Each municipality in Lithuania is governed by a municipal council and a mayor, who is a member of the municipal council. The number of members, elected on a four-year term, in each municipal council depends on the size of the municipality and varies from 15 (in municipalities with fewer than 5,000 residents) to 51 (in municipalities with more than 500,000 residents). 1,498 municipal council members were elected in 2023. Members of the council, with the exception of the mayor, are elected using proportional representation. Starting with 2015, the mayor is elected directly by the majority of residents of the municipality.[126] Social Democratic Party of Lithuania won the most positions in the 2023 elections (358 municipal council seats and 17 mayors).[127]

As of 2024, the number of seats in the European Parliament allocated to Lithuania was 11.[128] Ordinary elections take place on a Sunday on the same day as in other EU countries. The vote is open to all citizens of Lithuania, as well as citizens of other EU countries that permanently reside in Lithuania, who are at least 18 years old on the election day. To be eligible for election, candidates must be at least 21 years old on the election day, a citizen of Lithuania or a citizen of another EU country permanently residing in Lithuania. Candidates are not allowed to stand for election in more than one country. Persons serving or due to serve a sentence imposed by the court 65 days before the election are not eligible. Also, judges, citizens performing military service, and servicemen of professional military service and officials of statutory institutions and establishments may not stand for election.[129] Eight political parties gained seats in the 2024 elections.[130]

Law and law enforcement

The first attempt to

In 1934–1935, Lithuania held the first mass trial of the Nazis in Europe, the convicted were sentenced to imprisonment in a heavy labor prison and capital punishments.[133]

After regaining of independence in 1990, the largely modified Soviet legal codes were in force for about a decade. The current

The

Lithuania, after breaking away from the Soviet Union, had a difficult crime situation, however, the Lithuanian law enforcement agencies fought crime over the years, making Lithuania a reasonably safe country.[137] Crime in Lithuania has been declining rapidly.[138] Law enforcement in Lithuania is primarily the responsibility of local Lietuvos policija (Lithuanian Police) commissariats. They are supplemented by the Lietuvos policijos antiteroristinių operacijų rinktinė Aras (Anti-Terrorist Operations Team of the Lithuanian Police Aras), Lietuvos kriminalinės policijos biuras (Lithuanian Criminal Police Bureau), Lietuvos policijos kriminalistinių tyrimų centras (Lithuanian Police Forensic Research Center) and Lietuvos kelių policijos tarnyba (Lithuanian Road Police Service).[139]

In 2017, there were 63,846 crimes registered in Lithuania. Of these, thefts comprised a large part with 19,630 cases (13.2% less than in 2016). While 2,835 crimes were serious and very serious (crimes that may lead to more than six years imprisonment), which is 14.5% less than in 2016. In total, 129 homicides or attempted homicide occurred (19.9% less than in 2016), while serious bodily harm was registered 178 times (17.6% less than in 2016). Another problematic crime contraband cases also decreased by 27.2% from 2016 numbers. Meanwhile, crimes in electronic data and information technology security fields noticeably increased by 26.6%.[140] In the 2013 Special Eurobarometer, 29% of Lithuanians said that corruption affects their daily lives (EU average 26%). Moreover, 95% of Lithuanians regarded corruption as widespread in their country (EU average 76%), and 88% agreed that bribery and the use of connections is often the easiest way of obtaining certain public services (EU average 73%).[141] Though, according to local branch of Transparency International, corruption levels have been decreasing over the past decade.[142]

Capital punishment in Lithuania was suspended in 1996 and eliminated in 1998.[143] Lithuania has the highest number of prison inmates in the EU. According to scientist Gintautas Sakalauskas, this is not because of a high criminality rate in the country, but due to Lithuania's high repression level and the lack of trust of the convicted, who are frequently sentenced to imprisonment.[144]

Administrative divisions

The current system of administrative division was established in 1994 and modified in 2000 to meet the requirements of the European Union. The country's 10 counties (Lithuanian: singular – apskritis, plural – apskritys) are subdivided into 60 municipalities (Lithuanian: singular – savivaldybė, plural – savivaldybės), and further divided into 546 elderships (Lithuanian: singular – seniūnija, plural – seniūnijos). There are also 5 distinct cultural regions in Lithuania – Dzūkija, Aukštaitija, Suvalkija, Samogitia and Lithuania Minor, which are recognized by the state.

Municipalities have been the most important unit of administration in Lithuania since the system of

Elderships, numbering over 500, are the smallest administrative units and do not play a role in national politics. They provide necessary local public services—for example, registering births and deaths in rural areas. They are most active in the social sector, identifying needy individuals or families and organizing and distributing welfare and other forms of relief.[147] Some citizens feel that elderships have no real power and receive too little attention, and that they could otherwise become a source of local initiative for addressing rural problems.[148]

| County | Area (km2) | Population (2023)[149] | GDP (billion EUR)[150] | GDP per capita (EUR)[150] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alytus County | 5,425 | 135,367 | 1.8 | 13,600 |

| Kaunas County | 8,089 | 580,333 | 13.7 | 23,900 |

| Klaipėda County | 5,209 | 336,104 | 7.0 | 21,300 |

| Marijampolė County | 4,463 | 135,891 | 2.0 | 14,400 |

| Panevėžys County | 7,881 | 211,652 | 3.6 | 17,100 |

| Šiauliai County | 8,540 | 261,764 | 4.6 | 17,600 |

| Tauragė County | 4,411 | 90,652 | 1.2 | 13,200 |

| Telšiai County | 4,350 | 131,431 | 2.2 | 16,900 |

| Utena County | 7,201 | 125,462 | 1.7 | 13,800 |

| Vilnius County | 9,731 | 851,346 | 29.4 | 35,300 |

| Lithuania | 65,300 | 2,860,002 | 67.4 | 23,800 |

Foreign relations

Lithuania became a member of the United Nations on 18 September 1991, and is a signatory to a number of its organizations and other international agreements. It is also a member of the

Lithuania has established diplomatic relations with 149 countries.[152]

In 2011, Lithuania hosted the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Ministerial Council Meeting. During the second half of 2013, Lithuania assumed the role of the presidency of the European Union.

Lithuania is also active in developing cooperation among northern European countries. It is a member of the interparliamentary Baltic Assembly, the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers and the Council of the Baltic Sea States.

Lithuania also cooperates with Nordic and the two other Baltic countries through the Nordic-Baltic Eight format. A similar format, NB6, unites Nordic and Baltic members of EU. NB6's focus is to discuss and agree on positions before presenting them to the Council of the European Union and at the meetings of EU foreign affairs ministers.

The Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS) was established in Copenhagen in 1992 as an informal regional political forum. Its main aim is to promote integration and to close contacts between the region's countries. The members of CBSS are Iceland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Germany, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Russia, and the European Commission. Its observer states are Belarus, France, Italy, Netherlands, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ukraine.

The Nordic Council of Ministers and Lithuania engage in political cooperation to attain mutual goals and to determine new trends and possibilities for joint cooperation. The council's information office aims to disseminate Nordic concepts and to demonstrate and promote Nordic cooperation.

Lithuania, together with the five Nordic countries and the two other Baltic countries, is a member of the Nordic Investment Bank (NIB) and cooperates in its NORDPLUS programme, which is committed to education.

The Baltic Development Forum (BDF) is an independent nonprofit organization that unites large companies, cities, business associations and institutions in the Baltic Sea region. In 2010 the BDF's 12th summit was held in Vilnius.[153]

Poland was highly supportive of Lithuanian independence, despite Lithuania's discriminatory treatment of its Polish minority.[154][155] The former Solidarity leader and Polish President Lech Wałęsa criticised the government of Lithuania over discrimination against the Polish minority and rejected Lithuania's Order of Vytautas the Great.[156] Lithuania maintains greatly warm mutual relations with Georgia and strongly supports its European Union and NATO aspirations.[157][158][159] During the Russo-Georgian War in 2008, when the Russian troops were occupying the territory of Georgia and approaching towards the Georgian capital Tbilisi, President Valdas Adamkus, together with the Polish and Ukrainian presidents, went to Tbilisi by answering to the Georgians request of the international assistance.[160][161] Shortly, Lithuanians and the Lithuanian Catholic Church also began collecting financial support for the war victims.[162][163]

In 2004–2009,

In 2013, Lithuania was elected to the

In 2018 Lithuania, along with Latvia and Estonia were awarded the Peace of Westphalia Prize – for their exceptional model of democratic development and contribution to peace in the continent.[170] In 2019 Lithuania condemned the Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria.[171] In December 2021, Lithuania reported that in an escalation of the diplomatic spat with China over its relations with Taiwan,[172] China had stopped all imports from Lithuania.[173] According to Lithuanian intelligence agencies, in 2023 there was an increase in Chinese intelligence activity against Lithuania, including cyberespionage and increased focus on Lithuania's internal affairs and foreign policy.[174]

The 2023 NATO summit was held in the Lithuanian capital Vilnius.[175]

Military

The Lithuanian Armed Forces is the name for the unified armed forces of

The Lithuanian Armed Forces consist of some 20,000 active personnel, which may be supported by

Lithuania became a full member of

Beginning in summer of 2005, Lithuania was part of the

The Lithuanian National Defence Policy aims to guarantee the preservation of the independence and sovereignty of the state, the integrity of its land, territorial waters and airspace, and its constitutional order. Its main strategic goals are to defend the country's interests, and to maintain and expand the capabilities of its armed forces so they may contribute to and participate in the missions of NATO and European Union member states.[181]

The

According to NATO, in 2020, Lithuania allocated 2.13% of its

Lithuania's president

Economy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Lithuania has an open and

Agricultural products and food comprise 18% of exports; other major sectors include chemical products and plastics (18%), machinery and appliances (16%), mineral products (15%), wood and furniture (13%).[191] As of 2016[update] more than half of exports go to 7 countries including Russia (14%), Latvia (10%), Poland (9%), Germany (8%), Estonia (5%), Sweden (%) and the UK (4%).[192] Exports equaled 81% of GDP in 2017.[193]

GDP experienced very high real growth rates for the decade up to 2009, peaking at 11% in 2007. As a result, the country was often termed a

On average, more than 95% of all foreign direct investment comes from EU countries. Sweden is historically the largest investor with 20% – 30% of FDI.[197] FDI into Lithuania spiked in 2017, reaching its highest ever recorded number of greenfield investment projects. In 2017, Lithuania was third, after Ireland and Singapore by the average job value of investment projects.[198] The US was the leading source country in 2017, 25% of total FDI. Next up were Germany and the UK, each representing 11% of total project numbers.[199] Based on the Eurostat's data, in 2017, the value of exports recorded the most rapid growth not only in the Baltic countries, but across Europe, which was 17%.[200]

Between 2004 and 2016, one out of five Lithuanians emigrated, primarily due to insufficient income for residents;[201] secondarily seeking to study. Long term emigration and economic growth has resulted in a shortage in the labor market[202] and growth in salaries being larger than growth in labor efficiency.[203] Unemployment in 2017 was 8%.[204]

As of 2022, Lithuanian

Lithuania has a

Agriculture

Agriculture in Lithuania dates to the

In 2016, agricultural production was €2.3 billion.

Organic farming is becoming more popular. The status of organic growers and producers is granted by the public body Ekoagros. In 2016, there were 2539 such farms that occupied 225,542 hectares. Of these, 43% were cereals, 31% perennial grasses, 14% leguminous crops and 12% others.[219]

Science and technology

The foundation of the

The world wars of the 20th century severely diminished Lithuanian science and academia, although Lithuanian scholars and scientists managed to succeed, particularly abroad, including philosopher

Lasers and biotechnology are flagship fields of the Lithuanian science and high-tech industry.[229][230] Šviesos konversija ("Light Conversion") has developed a femtosecond laser system that has 80% market share worldwide, with applications in DNA research, ophthalmological surgeries, and nanotechnology.[231][232] The Vilnius University Laser Research Center has developed one of the most powerful femtosecond lasers in the world dedicated primarily to oncological diseases.[233] In 1963, Vytautas Straižys and his colleagues created Vilnius photometric system that is used in astronomy.[234] Noninvasive intracranial pressure and blood flow measuring devices were developed by KTU scientist A. Ragauskas.[235] Kęstutis Pyragas contributed to the study of chaos theory with his method of delayed feedback control, the Pyragas method. Kavli Prize laureate Virginijus Šikšnys is known for his discoveries in CRISPR, namely with respect to CRISPR-Cas9.[236][237]

Lithuania has launched three satellites to space:

Lithuania in 2018 became an Associated Member State of CERN.[243] Two CERN incubators in Vilnius and Kaunas will be hosted.[244] The most advanced scientific research is being conducted at the Life Sciences Center,[245] Center For Physical Sciences and Technology.[246]

As of 2016 calculations, yearly growth of Lithuania's biotech and life science sector was 22% over the past 5 years. 16 academic institutions, 15 R&D centres (science parks and innovation valleys) and more than 370 manufacturers operate in the Lithuanian life science and biotech industry.[247]

In 2008 the Valley development programme was started aiming to upgrade Lithuanian scientific research infrastructure and encourage business and science cooperation. Five R&D Valleys were launched – Jūrinis (maritime technologies), Nemunas (agro, bioenergy, forestry), Saulėtekis (laser and light, semiconductor), Santara (biotechnology, medicine), Santaka (sustainable chemistry and pharmacy).[248] Lithuanian Innovation Center is created to provide support for innovations and research institutions.[249]

Lithuania ranks moderately in the

Tourism

Statistics from 2023 showed 1.4 million tourists from foreign countries visited Lithuania and spent at least one night. The largest number of tourists came from Poland (173,500), Latvia (144,300), Belarus (141,900), Germany (127,400), the United Kingdom (74,200), the United States (69,700), Ukraine (67,000), and Estonia (61,300).[253]

Domestic tourism has been on the rise as well. Currently there are up to 1000 places of attraction in Lithuania. Most tourists visit the big cities—Vilnius, Klaipėda, and Kaunas, seaside resorts, such as Neringa, Palanga, and Spa towns – Druskininkai, Birštonas.[254]

Hot air ballooning is popular, especially in Vilnius and Trakai. Bicycle tourism is growing, especially the Lithuanian Seaside Cycle Route. EuroVelo routes EV10, EV11, EV13 go through Lithuania. The total length of bicycle tracks amounts to 3769 km (of which 1988 km is asphalt pavement).[255] Nemunas Delta Regional Park and Žuvintas biosphere reserve are known for birdwatching.[256]

The total contribution of tourism to GDP had been forecast to rise to €3.2 billion, 7% of GDP by 2027,[257] but has decreased to €1.7 billion, 2.3% of GDP in 2023, although it is rising post COVID-19 pandemic.[258]

Infrastructure

Communication

Lithuania has a well developed communications infrastructure. The country has 2.8 million citizens[259] and 5 million SIM cards.[260] The largest LTE (4G) mobile network covers 97% of Lithuania's territory.[261] Usage of fixed phone lines has been rapidly decreasing due to rapid expansion of mobile-cellular services.[262]

In 2017, Lithuania was top 30 in the world by average mobile broadband speeds and top 20 by average fixed broadband speeds.[263] Lithuania was also top 7 in 2017 in the List of countries by 4G LTE penetration. In 2016, Lithuania was ranked 17th in United Nations' e-participation index.[264][265]

There are four TIER III datacenters in Lithuania.[266] Lithuania is 44th globally ranked country on data center density according to Cloudscene.[267]

Long-term project (2005–2013) – Development of Rural Areas Broadband Network (RAIN) was started with the objective to provide residents, state and municipal authorities and businesses with fibre-optic broadband access in rural areas. RAIN infrastructure allows 51 communications operators to provide network services to their clients. The project was funded by the European Union and the Lithuanian government.

Transport

Lithuania received its first railway connection in the middle of the 19th century, when the

Transportation is the third largest sector in Lithuanian economy.[278] Lithuanian transport companies drew attention in 2016[279] and 2017[280] with huge and record-breaking orders of trucks. Almost 90% of commercial truck traffic in Lithuania is international transports, the highest of any EU country.[281]

Lithuania has an extensive network of motorways. WEF grades Lithuanian roads at 4.7 / 7.0[282] and Lithuanian road authority (LAKD) at 6.5 / 10.0.[283]

The Port of Klaipėda is the only commercial cargo port in Lithuania. In 2011 45.5 million tons of cargo were handled (including Būtingė oil terminal figures)[284] Port of Klaipėda is outside of EU's 20 largest ports,[285][286] but it is the eighth largest port in the Baltic Sea region[287][288] with ongoing expansion plans.[289]

As of 2022, the LIWA (Lithuanian Inland Waterways Authority, Vidaus vandens keliu direkcija in Lithuanian) is developing a strategy to resurrect cargo shipping on the Nemunas. Its fleet of electric ships will travel 260 km between the port of Klaipda on the Baltic Sea coast and the industrial and transportation centre of Kaunas.[290] The project is anticipated to need a €75.7 million initial investment in total. and estimated to eliminate 48 000 truck trips annually.[291][292]

Energy

Systematic diversification of energy imports and resources is Lithuania's key energy strategy.[296] Long-term aims were defined in National Energy Independence strategy in 2012 by Lietuvos Seimas.[297] It was estimated that strategic energy independence initiatives will cost €6.3–7.8 billion in total and provide annual savings of €0.9–1.1 billion.

After the decommissioning of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant, Lithuania turned from electricity exporter to electricity importer. Unit No. 1 was closed in December 2004, as a condition of Lithuania's entry into the European Union; Unit No. 2 was closed down on 31 December 2009. Proposals have been made to construct a new – Visaginas Nuclear Power Plant in Lithuania.[298] However, a non-binding referendum held in October 2012 clouded the prospects for the Visaginas project, as 63% of voters said no to a new nuclear power plant.[299]

The country's main primary source of electrical power is Elektrėnai Power Plant. Other primary sources of Lithuania's electrical power are Kruonis Pumped Storage Plant and Kaunas Hydroelectric Power Plant. Kruonis Pumped Storage Plant is the only in the Baltic states power plant to be used for regulation of the power system's operation with generating capacity of 900 MW for at least 12 hours.[300] As of 2015[update], 66% of electrical power was imported.[301] First geothermal heating plant (Klaipėda Geothermal Demonstration Plant) in the Baltic Sea region was built in 2004.

Lithuania–Sweden submarine electricity interconnection NordBalt and Lithuania–Poland electricity interconnection LitPol Link were launched at the end of 2015.[302]

In 2018, synchronising the Baltic states' electricity grid with the

In order to break down

Demographics

Since the Neolithic period, the demographics of Lithuania have stayed fairly homogenous. There is a high probability that the inhabitants of present-day Lithuania have similar genetic compositions to their ancestors,[309][310][311] although without being actually isolated from them.[312] The Lithuanian population appears to be relatively homogeneous, without apparent genetic differences among ethnic subgroups.[313]

A 2004 analysis of

In 2021, the age structure of the population was as follows:

- 0–14 years, 14.86% (male 214,113/female 203,117)

- 15–64 years: 65.19% (male 896,400/female 934,467)

- 65 years and over: 19.95% (male 195,269/female 365,014).[315]

The median age in 2022 was 44 years (male: 41, female: 47).[315]

Lithuania has a

Functional urban areas

Functional urban areas[316]

|

Population (2023) |

|---|---|

| Vilnius urban area | |

| Kaunas urban area | |

| Panevėžys urban area |

Ethnic groups and languages

Lithuania has the most homogeneous population in the Baltic States. Ethnic Lithuanians make up about five-sixths of the country's population. In 2024, 82.6% of the 2,809,977 Lithuania's residents were ethnic

The official language is Lithuanian, but in some areas there is a significant presence of minority languages such as Polish, Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian. The greatest presence of minorities and the use of these languages are in Šalčininkai, Visaginas, and Vilnius District.[318] In 1941, Lithuania’s Jewish population reached its peak at approximately 250,000 people, making up about 10% of the total population. Today, however, it has dwindled to a very small number. Yiddish is spoken by members of the tiny remaining Jewish community in Lithuania. The state laws guarantee education in minority languages and there are numerous publicly funded schools in the areas populated by minorities, with Polish as the language of instruction being the most widely available.[322]

According to the survey carried out within the framework of the

Urbanization

There has been a steady

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vilnius  Kaunas |

1 | Vilnius | Vilnius | 607,404 | 11 | Kėdainiai | Kaunas | 23,323 |  Klaipėda  Šiauliai |

| 2 | Kaunas | Kaunas | 303,978 | 12 | Ukmergė | Vilnius | 21,954 | ||

| 3 | Klaipėda | Klaipėda | 160,885 | 13 | Telšiai | Telšiai | 21,834 | ||

| 4 | Šiauliai | Šiauliai | 111,971 | 14 | Tauragė | Tauragė | 21,404 | ||

| 5 | Panevėžys | Panevėžys | 85,774 | 15 | Visaginas | Utena | 19,114 | ||

| 6 | Alytus | Alytus | 50,741 | 16 | Palanga | Klaipėda | 18,551 | ||

| 7 | Marijampolė | Marijampolė | 36,240 | 17 | Plungė | Telšiai | 17,031 | ||

| 8 | Mažeikiai | Telšiai | 33,303 | 18 | Kretinga | Klaipėda | 16,952 | ||

| 9 | Jonava | Kaunas | 26,680 | 19 | Šilutė | Klaipėda | 15,985 | ||

| 10 | Utena | Utena | 25,587 | 20 | Radviliškis | Šiauliai | 15,486 | ||

Health

Lithuania provides free state-funded healthcare to all citizens and registered long-term residents.[330] It co-exists with a significant private healthcare sector. In 2003–2012, the network of hospitals was restructured, as part of wider healthcare service reforms. It started in 2003–2005 with the expansion of ambulatory services and primary care.[331] In 2016, Lithuania ranked 27th in Europe in the

As of 2023[update], Lithuanian life expectancy at birth was 76.0 (70.6 years for males and 81.6 for females)[333] and the infant mortality rate was 2.99 per 1,000 births.[334] The annual population growth rate increased by 0.3% in 2007. Lithuania has seen a dramatic rise in suicides in the 1990s.[335] The suicide rate has been constantly decreasing since, but it still remains the highest in the EU and one of the highest in the OECD. The suicide rate as of 2019 is 20.2 per 100,000 people.[335] Suicide in Lithuania has been a subject of research, but the main reasons behind the high rate are thought[who?] to be both psychological and economic, including: social transformations and economic recessions, alcoholism, lack of tolerance in the society and bullying.[336]

By 2000, the vast majority of Lithuanian health care institutions were non-profit-making enterprises and a private sector developed, providing mostly outpatient services which are paid for out-of-pocket. The Ministry of Health also runs a few health care facilities and is involved in the running of the two major Lithuanian teaching hospitals. It is responsible for the State Public Health Centre which manages the public health network including ten county public health centres with their local branches. The ten counties run county hospitals and specialised health care facilities.[337]

There is Compulsory Health Insurance for the Lithuanian residents. There are 5 Territorial Health Insurance Funds, covering Vilnius, Kaunas, Klaipėda, Šiauliai and Panevėžys. Contributions for people who are economically active are 9% of income.[338]

Emergency medical services are provided free of charge to all residents. Access to the secondary and tertiary care, such as hospital treatment, is normally via referral by a general practitioner.[339] Lithuania also has one of the lowest health care prices in Europe.[340]

Religion

According to the 2021 census, 74.2% of residents of Lithuania were Catholics.

3.7% of the population are Eastern Orthodox, mainly among the Russian minority.[3] The community of Old Believers (0.6% of population) dates back to the 1660s.

Hinduism is a minority religion and a fairly recent development in Lithuania. Hinduism is spread in Lithuania by Hindu organizations:

The historical communities of Lipka Tatars maintain Islam as their religion. Lithuania was historically home to a significant Jewish community and was an important centre of Jewish scholarship and culture from the 18th century until the eve of World War II. Of the approximately 220,000 Jews who lived in Lithuania in June 1941, almost all were killed during the Holocaust.[344][345] The Lithuanian Jewish community numbered about 4,000 at the end of 2009.[346]

Education

The Constitution of Lithuania mandates ten-year education ending at age 16 and guarantees a free public higher education for students deemed 'good'.[355] The Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania proposes national educational policies and goals that are then voted for in the Seimas. Laws govern long-term educational strategy along with general laws on standards for higher education, vocational training, law and science, adult education, and special education.[356] 5.4% of GDP or 15.4% of total public expenditure was spent for education in 2016.[357]

According to the World Bank, the literacy rate among Lithuanians aged 15 years and older is 100%.[358] School attendance rates are above the EU average and school leave is less common than in the EU. According to Eurostat Lithuania leads among other countries of the European Union in people with secondary education (93.3%).[359] Based on OECD data, Lithuania is among the top 5 countries in the world in postsecondary (tertiary) education attainment.[360] As of 2022[update], 58.15% of the population aged 25 to 34, and 33.28% of the population aged 55 to 64 had completed tertiary education.[361] The share of tertiary-educated 25–64-year-olds in STEM (Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields in Lithuania were above the OECD average (29% and 26% respectively), similarly to business, administration and law (25% and 23% respectively).[362]

Modern Lithuanian education system has multiple structural problems. Insufficient funding, quality issues, and decreasing student population are the most prevalent. Lithuanian teacher salaries below EU average, despite significant increases since 2011.

As of 2008[update], there were 15 public and 6 private universities as well as 16 public and 11 private colleges in Lithuania (see:

Culture

Lithuanian language

The Lithuanian language (lietuvių kalba) is the official state language of Lithuania and is recognized as one of the official languages of the European Union. There are about 2.96 million native Lithuanian speakers in Lithuania and about 0.2 million abroad.

Lithuanian is a

There are two main dialects of the Lithuanian language:

The groundwork for written Lithuanian was laid in 16th and 17th centuries by Lithuanian noblemen and scholars, who promoted Lithuanian language, created dictionaries and published books – Mikalojus Daukša, Stanislovas Rapolionis, Abraomas Kulvietis, Jonas Bretkūnas, Martynas Mažvydas, Konstantinas Sirvydas, Simonas Vaišnoras-Varniškis.[385] The first grammar book of the Lithuanian language Grammatica Litvanica was published in Latin in 1653 by Danielius Kleinas.

Jonas Jablonskis' works and activities are especially important for the Lithuanian literature moving from the use of dialects to a standard Lithuanian language. The linguistic material which he collected was published in the 20 volumes of Academic Dictionary of Lithuanian and is still being used in research and in editing of texts and books. He also introduced the letter ū into Lithuanian writing.[386]

Literature

There is a great deal of Lithuanian literature written in Latin, the main scholarly language of the Middle Ages. The edicts of the Lithuanian King Mindaugas are the prime example of the literature of this kind. The Letters of Gediminas are another crucial heritage of the Lithuanian Latin writings.

One of the first Lithuanian authors who wrote in Latin was

17th century Lithuanian scholars also wrote in Latin –

Lithuanian literary works in the Lithuanian language started being first published in the 16th century. In 1547 Martynas Mažvydas compiled and published the first printed Lithuanian book Katekizmo prasti žodžiai (The Simple Words of Catechism), which marks the beginning of literature, printed in Lithuanian. He was followed by Mikalojus Daukša with Katechizmas. In the 16th and 17th centuries, as in the whole Christian Europe, Lithuanian literature was primarily religious.

The evolution of the old (14th–18th century) Lithuanian literature ends with Kristijonas Donelaitis, one of the most prominent authors of the Age of Enlightenment. Donelaitis' poem Metai (The Seasons) is a landmark of the Lithuanian fiction literature, written in hexameter.[389]

With a mix of

20th-century Lithuanian literature is represented by Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas, Antanas Vienuolis, Bernardas Brazdžionis, Antanas Škėma, Balys Sruoga, Vytautas Mačernis and Justinas Marcinkevičius.[citation needed]

In 21st century debuted Kristina Sabaliauskaitė, Renata Šerelytė, Valdas Papievis, Laura Sintija Černiauskaitė, Rūta Šepetys.[citation needed]

Architecture

Several

Lithuania is also known for numerous castles. About twenty castles exist in Lithuania. Some castles had to be rebuilt or survive partially. Many Lithuanian nobles' historic palaces and manor houses have remained till the nowadays and were reconstructed.[393] Lithuanian village life has existed since the days of Vytautas the Great. Zervynos and Kapiniškiai are two of many ethnographic villages in Lithuania.[394] Rumšiškės is an open space museum where old ethnographic architecture is preserved.

During the interwar period, Art Deco, Lithuanian National Romanticism architectural style buildings were constructed in the Lithuania's temporary capital Kaunas. Its architecture is regarded as one of the finest examples of the European Art Deco and has received the European Heritage Label.[395]

Arts and museums

The

Perhaps the most renowned figure in Lithuania's art community was the composer Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911), an internationally renowned musician. The 2420 Čiurlionis asteroid, identified in 1975, honors his achievements. The M. K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum, as well as the only military museum in Lithuania, Vytautas the Great War Museum, are located in Kaunas. Franciszek Smuglewicz, Jan Rustem, Józef Oleszkiewicz and Kanuty Rusiecki are the most prominent Lithuanian painters of the 18th and 19th centuries.[398]

Theatre

Lithuania has theatres in

Lithuanian theatre directors include Eimuntas Nekrošius, Jonas Vaitkus, Cezaris Graužinis, Gintaras Varnas, Dalia Ibelhauptaitė and Artūras Areima. Actors include Dainius Gavenonis, Rolandas Kazlas, Saulius Balandis and Gabija Jaraminaitė.[403]

Theatre director Oskaras Koršunovas was awarded the Swedish Commander Grand Cross – the Order of the Polar Star.[404]

Cinema

On 28 July 1896,

In 2018, 4,265,414 cinema tickets were sold in Lithuania with the average price of €5.26.[406]

Music

Lithuanian folk music belongs to

Italian artists organized the first opera in Lithuania on 4 September 1636 at the Palace of the Grand Dukes by the order of Władysław IV Vasa.[409] Currently, operas are staged at the Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre and also by independent troupe Vilnius City Opera.

In Lithuania,

Modern classical composers emerged in seventies – Bronius Kutavičius, Feliksas Bajoras, Osvaldas Balakauskas, Onutė Narbutaitė, Vidmantas Bartulis and others. Most of those composers explored archaic Lithuanian music and its harmonic combination with modern minimalism and neoromanticism.[415]

Jazz scene was active even during the years of Soviet occupation. In 1970–71 the Ganelin/Tarasov/Chekasin trio established the Vilnius Jazz School.[416] Most known annual events are Vilnius Jazz Festival, Kaunas Jazz, Birštonas Jazz. Music Information Centre Lithuania (MICL) collects, promotes and shares information on Lithuanian musical culture.

Rock and protest music

After the

In the early independence years, rock band Foje was particularly popular and gathered tens of thousands of spectators to the concerts.[423] After disbanding in 1997, Foje vocalist Andrius Mamontovas remained one of the most prominent Lithuanian performers and an active participant in various charity events.[424] Marijonas Mikutavičius is famous for creating unofficial Lithuania sport anthem Trys milijonai (Three millions) and official anthem of the EuroBasket 2011 Nebetyli sirgaliai (English version was named Celebrate Basketball).[425][426]

Cuisine

Lithuanian cuisine features the products suited to the cool and

Dairy products are an important part of traditional Lithuanian cuisine. These include white cottage cheese (varškės sūris), curd (varškė), soured milk (rūgpienis), sour cream (grietinė), butter (sviestas), and sour cream butter kastinis. Traditional meat products are usually seasoned, matured and smoked – smoked sausages (dešros), lard (lašiniai), skilandis, smoked ham (kumpis). Soups (sriubos) – boletus soup (baravykų sriuba), cabbage soup (kopūstų sriuba), beer soup (alaus sriuba), milk soup (pieniška sriuba), cold-beet soup (šaltibarščiai) and various kinds of porridges (košės) are part of tradition and daily diet. Freshwater fish, herring, wild berries and mushrooms, honey are highly popular diet to this day.[428][429]

One of the oldest and most fundamental Lithuanian food products was and is rye bread. Rye bread is eaten every day for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Bread played an important role in family rituals and agrarian ceremonies.[430]

Lithuanians and other nations that once formed part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania share many dishes and beverages. German traditions also influenced Lithuanian cuisine, introducing pork and potato dishes, such as potato pudding (kugelis or kugel) and potato sausages (vėdarai), as well as the baroque tree cake known as Šakotis. The most exotic of all the influences is Eastern (Karaite) cuisine – the kibinai are popular in Lithuania. Lithuanian noblemen usually hired French chefs, so French cuisine influence came to Lithuania in this way.[431]

Balts were using mead (midus) for thousands of years.[432] Beer (alus) is the most common alcoholic beverage. Lithuania has a long farmhouse beer tradition, first mentioned in 11th century chronicles. Beer was brewed for ancient Baltic festivities and rituals.[433] Farmhouse brewing survived to a greater extent in Lithuania than anywhere else, and through accidents of history the Lithuanians then developed a commercial brewing culture from their unique farmhouse traditions.[434][435] Lithuania is top 5 by consumption of beer per capita in Europe in 2015, counting 75 active breweries, 32 of them are microbreweries.[436] The microbrewery scene in Lithuania has grown, with a number of bars focusing on these beers opening in Vilnius and other parts of the country.[citation needed]

Eight Lithuanian restaurants are listed in the White Guide Baltic Top 30.[437] The local „30 geriausių restoranų” guide lists top domestic places,[438] and Lithuanian restaurants will appear in the Michelin Guide on 13 June 2024.[439]

Media

The

In 2021, the best-selling daily national newspapers in Lithuania were

In 2021, the most popular national

The most popular

Public holidays and festivals

As a result of a thousand-years history, Lithuania has two

Kaziuko mugė is an annual fair held since the beginning of the 17th century that commemorates the anniversary of Saint Casimir's death and gathers thousands of visitors and many craftsmen. Other notable festivals are Vilnius International Film Festival, Kauno Miesto Diena, Klaipėda Sea Festival, Mados infekcija, Vilnius Book Fair, Vilnius Marathon, Devilstone Open Air, Apuolė 854, Great Žemaičių Kalvarija Festival.

| Public holidays in Lithuania | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | English name | Local name | Remarks |

| 1 January | New Year's Day | Naujųjų metų diena | |

| 16 February | Day of Restoration of the State of Lithuania (1918) | Lietuvos valstybės atkūrimo diena | |

| 11 March | Day of Restoration of Independence of Lithuania (1990) | Lietuvos nepriklausomybės atkūrimo diena | |

| Moveable Sunday | Easter Sunday |

Velykos | Commemorates resurrection of Jesus. The first Sunday after the full moon that occurs on or soonest after 21 March. |

| The day after Easter Sunday |

Easter Monday | Antroji Velykų diena | |

| 1 May | International Workers' Day | Tarptautinė darbo diena | |

| First Sunday in May | Mother's Day | Motinos diena | |

| First Sunday in June | Father's Day | Tėvo diena | |

| 24 June | St. John's Day / Day of Dew |

Joninės / Rasos |

Celebrated according to mostly pagan traditions ( Saint Jonas Day ).

|

| 6 July | Statehood Day | Valstybės (Lietuvos karaliaus Mindaugo karūnavimo) ir Tautiškos giesmės diena | Celebrates the 1253 coronation of King of Lithuania, and the national anthem of Lithuania .

|

| 15 August | Assumption Day | Žolinė (Švenčiausios Mergelės Marijos ėmimo į dangų diena) | Also marked according to pagan traditions, celebrating the goddess Žemyna and noting the mid-August as the middle between summer and autumn. |

| 1 November | All Saints' Day | Visų šventųjų diena | Halloween is increasingly popular and is also informally celebrated on the eve (31 October). |

| 2 November | All Souls' Day | Mirusiųjų atminimo (Vėlinių) diena | |

| 24 December | Christmas Eve | Kūčios | |

| 25 and 26 December | Christmas Day |

Kalėdos | Commemorates birth of Jesus. |

Sports

Lithuania has won a total of

Lithuania hosted the 2021 FIFA Futsal World Cup, the first time Lithuania had hosted a FIFA tournament.[446]

Few Lithuanian athletes have found success in

See also

Notes

- ^ Lithuania uses ISO 8601 standard for date and time.

- ^ /ˌlɪθjuˈeɪniə/ ⓘ LITH-ew-AY-nee-ə;[16] Lithuanian: Lietuva [lʲiətʊˈvɐ]

- ^ Lithuanian: Lietuvos Respublika [lʲiətʊˈvoːs rʲɛsˈpʊblʲɪkɐ]

- ^ CIA World Factbook[22] classifies it as eastern Europe, and Encyclopædia Britannica locates it in northeastern Europe.[23] Usage varies greatly, and controversially,[24]in press sources.

References

- ^ "Lithuania's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments through 2019" (PDF). Constitute Project. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Rodiklių duomenų bazė - Oficialiosios statistikos portalas". osp.stat.gov.lt.

- ^ Statistics Lithuania. Archivedfrom the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-9986-9216-7-7.

- ^ Veser, Ernst (23 September 1997). "Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's Concept – A New Political System Model" (PDF) (in English and Chinese). Department of Education, School of Education, University of Cologne. pp. 39–60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

Duhamel has developed the approach further: He stresses that the French construction does not correspond to either parliamentary or the presidential form of government, and then develops the distinction of 'système politique' and 'régime constitutionnel'. While the former comprises the exercise of power that results from the dominant institutional practice, the latter is the totality of the rules for the dominant institutional practice of the power. In this way, France appears as 'presidentialist system' endowed with a 'semi-presidential regime' (1983: 587). By this standard he recognizes Duverger's pléiade as semi-presidential regimes, as well as Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Lithuania (1993: 87).

- ^ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. United States: University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ISSN 1476-3419.

A pattern similar to the French case of compatible majorities alternating with periods of cohabitation emerged in Lithuania, where Talat-Kelpsa (2001) notes that the ability of the Lithuanian president to influence government formation and policy declined abruptly when he lost the sympathetic majority in parliament.

- ^ "Eurostat celebrates Lithuania". 16 February 2018. Eurostat. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Pradžia – Oficialiosios statistikos portalas". osp.stat.gov.lt. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 Edition. (Lithuania)". International Monetary Fund. 10 April 2024. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income". Eurostat. Archived from the original on 9 January 2025. Retrieved 18 January 2025.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Office of the Chief Archivist of Lithuania (4 July 2011). "V-117 Dėl Dokumentų rengimo taisyklių patvirtinimo". e-seimas.lrs.lt (in Lithuanian). Seimas. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "Kaip trumpuoju būdu rašyti datą?". vlkk.lt (in Lithuanian). Commission of the Lithuanian Language. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2.

- ^ "United Nations Statistics Division- Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49)-Geographic Regions". Unstats.un.org. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Lithuania - EU Vocabularies - Publications Office of the EU". op.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ "Lithuania". Europe Direct Strasbourg. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Lehmann, Alex (29 December 2014). "Lithuania joins the Eurozone". European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-7876-5015-5

- CIA World Factbook. 22 September 2021. Archivedfrom the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Lithuania". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Bershidsky, Leonid (10 January 2017). "Why the Baltics Want to Move to Another Part of Europe". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Bammesberger, Alfred (March 2012). "Lietuvà, Lithuania, and Chaucer's Lettow". Lituanus. 58 (1): 5–8.

- ISSN 0024-5089.

- ^ Vilnius. Key dates Archived 17 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 18 January 2007.

- Vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Archivedfrom the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Zigmas Zinkevičius. Kelios mintys, kurios kyla skaitant Alfredo Bumblausko Senosios Lietuvos istoriją 1009-1795m. Voruta, 2005.

- ISSN 1392-0677. Archived from the originalon 10 May 2022.

- ^ Dubonis, Artūras (1998). Lietuvos didžiojo kunigaikščio leičiai: iš Lietuvos ankstyvųjų valstybinių struktūrų praeities Leičiai of Grand Duke of Lithuania: from the past of Lithuanian stative structures (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos instituto leidykla.

- ^ Dubonis, Artūras (30 April 2020). "Leičiai | Orbis Lituaniae". LDKistorija.lt (in Lithuanian). Vilnius University. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ]

- ^ Patackas, Algirdas. "Lietuva, Lieta, Leitis, arba ką reiškia žodis "Lietuva"". Lrytas.lt (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- OCLC 39615701.

- ^ Kudirka, Juozas (1991). The Lithuanians: An Ethnic Portrait. Lithuanian Folk Culture Centre. p. 13.

- ISBN 978-3-11-086792-3.

- ^ Šapoka, Adolfas (1936). Lietuvos istorija (PDF). Kaunas: Šviesa. pp. 13–17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7618-0411-6.

- ]

- ^ Ochmański (1982), p. 37

- ^ Eidintas et al. (2013), pp. 24–25

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-16111-4.

- ^ a b "Lithuania (02/08)". U.S. Department of State.

- ISBN 5-420-00723-1

- ^ a b Gudavičius, Edvardas. "Mindaugas". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Lithuania - History". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 October 2024. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Gudavičius, Edvardas; Jasas, Rimantas. "Kryžiaus karai Baltijos regione". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Traidenis". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Petrauskas, Rimvydas. "Lietuvos Didžioji Kunigaikštystė". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Gediminaičiai". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Jogailaičiai". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b Jasas, Rimantas. "Liublino unija". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Andriulis, Vytautas. "Trečiasis Lietuvos Statutas". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Polonizacija". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Raila, Eligijus. "ATR nelaimių šimtmetis". Šaltiniai.info. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Kėdainių sutartis". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Lietuvių sukilimas prieš švedus". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "1661 12 03 Vilniaus pilyje kapituliavo rusų įgula". DELFI (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Emilija Platerytė". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian).

- ^ a b c d e "Lietuva Rusijos imperijos valdymo metais (1795–1914)". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "January Insurrection". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Simonas Daukantas". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian).

- ^ "Teodoras Narbutas". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian).

- ^ "XX a. pradžioje rusus suerzino paviešinti lietuvių knygnešystės mastai". Lithuanian National Radio and Television (in Lithuanian). 28 July 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Merkys, Vytautas. "Lietuvių tautinis judėjimas". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Lasinskas, Povilas. "Nepriklausomos Lietuvos valstybės atkūrimas (1918–1920)". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Miknys, Rimantas. "Józef Piłsudski". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Kauno istorija". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b Lasinskas, Povilas. "Lietuvos Respublika 1920–1940". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Lietuvos istorija". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Juodis, Darius. "Jonas Žemaitis". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ Ramanauskaitė-Skokauskienė, Auksutė. "Adolfas Ramanauskas". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ISBN 978-1-85743-136-0.

- ^ "Lithuania breaks away from the Soviet Union". The Guardian. London. 12 March 1990. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

Lithuania last night became the first republic to break away from the Soviet Union, by proclaiming the restoration of its pre-war independence. The newly-elected parliament, 'reflecting the people's will,' decreed the restoration of 'the sovereign rights of the Lithuanian state, infringed by alien forces in 1940,' and declared that from that moment Lithuania was again an independent state

- ^ Martha Brill Olcott (1990). "The Lithuanian Crisis". www.foreignaffairs.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

For over two years Lithuania has been moving toward reclaiming its independence. This drive reached a crescendo on 11 March 1990, when the Supreme Soviet of Lithuania declared the republic no longer bound by Soviet law. The act reasserted the independence Lithuania had declared more than seventy years before, a declaration unilaterally annulled by the U.S.S.R. in 1940 when it annexed Lithuania as the result of a pact between Stalin and Hitler.

- ^ a b c d e f Laurinavičius, Česlovas. "Lietuvos Respublika po 1990". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian).

- ^ "10 svarbiausių 1991–ųjų sausio įvykių, kuriuos privalote žinoti". 15min.lt. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ "On This Day 13 January 1991: Bloodshed at Lithuanian TV station". BBC News. 13 January 1991. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Bill Keller (14 January 1991). "Soviet crackdown; Soviet loyalists in charge after attack in Lithuania; 13 dead; curfew is imposed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-521-59938-2.

- ^ "WTO - Accessions: Lithuania". www.wto.org. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "Lithuania's membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)". Urm.lt. 5 February 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "Membership". Urm.lt. 6 January 2016. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ Kryptis, Dizaino (16 January 2008). "Lithuania has joined the Schengen Area". mfa.lt. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ Kropaite, Zivile (1 January 2015). "Lithuania joins Baltic neighbours in euro club". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "Lithuania officially becomes the 36th OECD member". lrv.lt. 5 July 2018. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "Lithuania President Re-elected on Anti-Russian Platform". VOA. 26 May 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Lithuania declares state of emergency after Russia invades Ukraine". Reuters. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Cook, Lorne (24 February 2022). "NATO vows to defend its entire territory after Russia attack". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ "2023 NATO Summit". NATO. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- Canada.ca. Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Jan S. Krogh. "Other Places of Interest: Central Europe". Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ "Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin – The BACC Project – 22–23 May 2006, Göteborg, Sweden" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ "Nida and The Curonian Spit, The Insider's Guide to Visiting". VanLife Tribe. 23 September 2016. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Aplinkos apsaugos įstatymas". e-tar.lt. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "EU climate action". European Commission. 23 November 2016. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Europa suskubo paskui Lietuvą: kuo skiriasi šalių užstato sistemos?". 15min.lt. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Gamta". lithuania.travel (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- PMID 28608869.

- ISBN 978-9955-815-27-3. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Lietuvos nacionaliniai parkai". aplinka.lt (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Regioniniai parkai". vstt.lt. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Draustiniai". vstt.lt. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Lithuania Ia. Protected Planet

- ^ "Apie gamtos paveldo objektus". vstt.lt. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Klimka, Libertas (26 March 2015). "Kodėl gandras – nacionalinis paukštis?". LRT (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Storks". Lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Lithuania – Biodiversity Facts". cbd.int. Archived from the original on 25 June 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "Fauna of Lithuania". TrueLithuania.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ a b (in Lithuanian) Nuo 1991 m. iki šiol paskelbtų referendumų rezultatai Archived 9 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Microsoft Word Document, Seimas. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ^ a b "Presidential Functions". lrp.lt. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Rezultatai – Respublikos Prezidento rinkimai 2019". rinkimai.maps.lt. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Nausėda claims landslide victory in Lithuania's presidential run-off". lrt.lt. 26 May 2024. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Seimo rinkimai". lrs.lt. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Baronienė, Daiva. "Teisę balsuoti Lietuvos moterys gavo vienos pirmųjų pasaulyje". Lzinios.lt. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Saarts, Tõnis. "Comparative Party System Analysis in Central and Eastern Europe: the Case of the Baltic States" (PDF). Studies of Transition States and Societies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Lithuanian parliament amends Constitution to allow direct mayoral elections". lrt.lt. 21 April 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ "Lietuvos Respublikos Seimo rinkimų įstatymas". e-tar.lt. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Lithuanian Social Democratic leader hails 'historic' election victory". lrt.lt. 28 October 2024. Archived from the original on 11 November 2024. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "Gintautas Paluckas confirmed as Lithuania's new prime minister". 24 November 2024.

- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania". The Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania. Archived from the original on 17 January 2006. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidento rinkimų įstatymas". e-tar.lt. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Nausėda claims landslide victory in Lithuania's presidential run-off". lrt.lt. 26 May 2024. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "Lietuvos Respublikos savivaldybių tarybų rinkimų įstatymas". e-tar.lt. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "2023 m. kovo 19 d. savivaldybių tarybų ir merų rinkimai". vrk.lt.

- ^ "Distribution of seats in the European Parliament". European Parliament.

- ^ "Lietuvos Respublikos rinkimų į Europos Parlamentą įstatymas". e-tar.lt. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "2024 m. birželio 9 d. rinkimai į Europos Parlamentą". vrk.lt.

- ^ a b c Matulienė, Snieguolė; Spruogis, Ernestas. "Lietuvos teisės šaltiniai". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Gegužės trečiosios konstitucija". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Gliožaitis, Algirdas. "Neumanno-Sasso byla" [The Case of Neumann-Sass]. Mažosios Lietuvos enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ "Lietuvos Konstitucija". lrs.lt. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2018.