William Dudley Chipley

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) |

William Dudley Chipley (June 6, 1840 – December 1, 1897) was an American railroad executive and politician who was instrumental in the building of the Pensacola and Atlantic Railroad and was a tireless promoter of Pensacola, his adopted city, where he was elected to one term as mayor, and later to a term as Florida state senator.

Following the

In 1877, Chipley helped Texas Rangers and Florida law officers subdue and arrest outlaw John Wesley Hardin aboard a train in Pensacola. Hardin was subsequently returned to Texas, convicted on outstanding murder charges, and imprisoned.[2]

Early life

Chipley was born in

Chipley moved with his parents back to Lexington when he was four years old, and was raised for all of his formative years in Kentucky. He graduated from the Kentucky Military Institute and Transylvania University.

Military service

After graduation from Transylvania, he enlisted in the

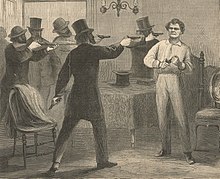

Ashburn murder trial

Chipley was later implicated and charged in the murder of George W. Ashburn by the Columbus Ku Klux Klan.

With former

Political intrigue, however, would ultimately undermine the case against Chipley and the other defendants. Stephens' connections with Democratic members of the Georgia House of Representatives lead to Democrats voting to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, a Republican goal, which in turn caused the re-admittance of Georgia to the Union and the invalidation of the military court proceedings.[12][13][14] As a result, Chipley and the others charged in Ashburn's death were released.[15]

Railroad executive

Chipley entered the railroad industry shortly after the Ashburn trial. He worked for the

Chipley's success in getting a railroad built through the Panhandle led the residents of Orange, Florida, to rename their town Chipley in 1882. In the same year, the town of Chipley, Georgia, near Columbus, was named for him, after he got the tracks of the Columbus and Rome Railroad extended to that community; the town's name was changed to Pine Mountain in 1958.[17]

Politics and death

Chipley created the Democratic Executive Committee in Muscogee County, Georgia in the late 1860s, and was its first director. He later served as director of the Florida Democratic Executive Committee.

Chipley served one term as the mayor of Pensacola (1887–1888). He also served in the Florida State Senate from 1895 to 1897, and lost his bid for

While on a trip to Washington, D.C., Chipley died on December 1, 1897. He was in the middle of a trip to lobby lawmakers to base more industrial endeavors in Florida. He was buried in Columbus, while the townspeople of Pensacola erected an obelisk in the Plaza Ferdinand VII in his honor.

See also

References

- OCLC 1091189008.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-1574415056. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- OCLC 1091189008.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ "The Murder of George W. Ashburn of Georgia". The New York Times. April 6, 1868.

- OCLC 1091189008.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - OCLC 1091189008.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Meade, George (1868). Report on the Ashburn Murder. U.S. Army Department of the South. p. 51.

- OCLC 1091189008.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - OCLC 1091189008.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ "Affairs in Atlanta". Macon Weekly Telegraph. July 10, 1868.

- ^ "The South". Chicago Tribune. July 11, 1868.

- ^ "Stand Firm!". Atlanta Constitution. July 21, 1868.

- ^ Telfair, Nancy (1929). A History of Columbus, Georgia 1828-1928. Historical Publishing Company. pp. 166–167.

- ^ "Suspension of the Military Commission". Atlanta Constitution. July 23, 1868.

- ^ "Return of the Prisoners". Columbus Daily Enquirer. July 26, 1868.

- ISBN 0738524212. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Harris County Historical Markers: The Iron Horse". georgiainfo.com. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

External links

- Pensacola (the Naples of America) and Its Surroundings Illustrated - Promotional pamphlet and travel guide compiled by Chipley when general manager of the Pensacola Railroad, 1877.

- Works by or about William Dudley Chipley at Internet Archive