Arthur W. Radford

Arthur W. Radford | |

|---|---|

VF-1B | |

| Battles / wars |

|

| Awards | Companion of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) |

| Signature | |

Arthur William Radford (27 February 1896 – 17 August 1973) was an

With an interest in ships and aircraft from a young age, Radford saw his first sea duty aboard the battleship

Noted as a strong-willed and aggressive leader, Radford was a central figure in the post-war debates on U.S. military policy, and was a staunch proponent of naval aviation. As commander of the Pacific Fleet, he defended the Navy's interests in an era of shrinking defense budgets, and was a central figure in the "

Retiring from the military in 1957, Radford continued to be a military adviser to several prominent politicians until his death in 1973. For his extensive service, he was awarded many military honors, and was the namesake of the Spruance-class destroyer USS Arthur W. Radford.

Early life

Arthur William Radford was born on 27 February 1896 in

Arthur began his school years at Riverside Public School, where he expressed an interest in the

Although Radford's first year at the academy was mediocre he applied himself to his studies in his remaining years there.

Military career

Radford's first duty was aboard the

In 1920, Radford reported to

Radford achieved the rank of

In July 1941, Radford was appointed commander of the Naval Air Station in

World War II

Aviation Training Division

Radford took command of the Aviation Training Division in Washington, D.C., on 1 December 1941, seven days before the attack on Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into World War II.[8] He was appointed as Director of Aviation Training for both the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and the Bureau of Navigation;[9] the double appointment helped to centralize training coordination for all naval aviators. With the U.S. mobilizing for war, Radford's office worked long hours six days a week in an effort to build up the necessary training infrastructure as quickly as possible. For several months, this around-the-clock work took up all of his time, and he later noted that walking to work was his only form of exercise for several months. During this time, he impressed colleagues with a direct and no-nonsense approach to work, while maintaining a demeanor that made him easy to work for.[8] He was promoted to captain soon after.[5]

Throughout 1942 he established and refined the administrative infrastructure for aviation training. Radford oversaw the massive growth of the training division, establishing separate sections for administration; Physical Training Service Schools; and training devices; and sections to train various aviators in flight, aircraft operation, radio operation, and gunnery. The section also organized technical training and wrote training literature. He also engineered the establishment of four field commands for pilot training. Air Primary Training Command commanded all pre-flight schools and

Radford was noted for thinking progressively and innovatively to establish the most effective and efficient training programs. He sought to integrate

Sea duty

By early 1943, with Radford's training programs established and functioning efficiently, he sought combat duty.

On 21 July 1943, Radford was given command of

Next, Radford and his carriers took part in an air attack and cruiser bombardment of

Major combat operations

Major operations in the Central Pacific began that November. Radford's next duty was in

The invasion began on 20 November. Radford's force was occupied with

Returning from Tarawa, Radford was reassigned as

Radford returned to Pearl Harbor on 7 October 1944, where he was appointed as commander of First Carrier Task Force,

"To every officer and man in this splendid group well done [.] In the last 45 days you have contributed much toward the victory announced today and I am proud of you."

On 29 December 1944, Radford was unexpectedly ordered to take command of Task Group 38.1 after its commander, Rear Admiral

Returning to the Third Fleet and being re-designated Task Group 38.4, the force began operating off the

Post-war years

Radford was promoted to vice admiral in late 1945.

After the war, Radford was a principal opponent to a plan to merge the

In 1948, Radford was appointed by President

Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet

In April 1949, Truman appointed Radford to the position of

"Revolt of the Admirals"

Despite his new office, Radford was soon recalled to Washington to continue hearings on the future of the

At the request of Congressman

Korean War

Shortly after the outbreak of the

Radford was an admirer of MacArthur and a proponent of his "

As commander of U.S. forces in the Philippines and Formosa, Radford accompanied President-elect Dwight D. Eisenhower on his three-day trip to Korea in December 1952.[36] Eisenhower was looking for an exit strategy for the stalemated and unpopular war, and Radford suggested threatening China with attacks on its Manchurian bases and the use of nuclear weapons.[33] This view was shared by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and UNC Commanding General Mark W. Clark, but had not been acted on when the armistice came in July 1953, at a time when the Chinese were struggling with domestic unrest.[37] Still, Radford's frankness during the trip and his knowledge of Asia made a good impression on Eisenhower, who nominated Radford to be his Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[33][38]

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

"I simply must find men who have the breadth of understanding and devotion to the country rather than to a single Service that will bring about better solutions than I get now. ... [strangely] enough the one man who sees this clearly is a Navy man who at one time was an uncompromising exponent of naval power and its superiority over any other kind of strength. That is Radford."

Eisenhower's official nomination for Radford came in mid-1953. Eisenhower was initially cautious about him because of his involvement in the

Military budget

Radford was integral in formulating and executing the "New Look" policy, reducing spending on conventional military forces to favor a strong

In 1956, Radford proposed protecting several military programs from funding cuts by reducing numbers of conventional forces, but the proposal was leaked to the press, causing an uproar in Congress and among U.S. military allies, and the plan was dropped. In 1957, after the other Joint Chiefs of Staff again disagreed on how to downsize force levels amid more budget restrictions, Radford submitted ideas for less dramatic force downsizing directly to Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson, who agreed to pass them along to Eisenhower.[42]

Foreign military policy

While Radford remained Eisenhower's principal adviser for the budget, they differed on matters of foreign policy.[42] Radford advocated the use of nuclear weapons and a firm military and diplomatic stance against China.[18] Early in his tenure, he suggested to Eisenhower a preventive war against China or the Soviet Union while the U.S. possessed a nuclear advantage and before it became entangled in conflicts in the Far East. Eisenhower immediately dismissed this idea.[42]

After France requested U.S. assistance for its

Later life

After his second term as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Radford opted to retire from the Navy in 1957 to enter the private sector. The same year

Radford died of cancer at age 77 on 17 August 1973

Dates of rank

United States Naval Academy Midshipman – Class of 1916

United States Naval Academy Midshipman – Class of 1916

| Ensign | Lieutenant (junior grade) | Lieutenant | Lieutenant Commander

|

Commander | Captain

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 June 1916 | 1 July 1917 | 1 January 1918 | 17 February 1927 | 1 July 1936 | 1 January 1942 |

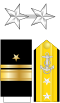

| Rear Admiral (lower half) | Rear Admiral (upper half) | Vice Admiral

|

Admiral |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-7 | O-8 | O-9 | O-10 |

|

|

|

|

| Never held | 21 July 1943 | 25 May 1946 | 7 April 1949 |

Awards and decorations

Radford's awards and decorations include the following:[46]

| ||

Naval Aviator Badge

| ||

| Navy Distinguished Service Medal with three stars |

Legion of Merit with star |

Navy Presidential Unit Citation

with two service stars |

| Navy Unit Commendation | World War I Victory Medal with service star |

American Defense Service Medal with service star |

| American Campaign Medal | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with seven battle stars |

World War II Victory Medal |

Navy Occupation Medal

|

National Defense Service Medal | Korean Service Medal |

| Order of Fiji | Companion of the Order of the Bath

|

Philippine Liberation Medal with service star |

References

Citations

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Muir 2001, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tucker 2009, p. 725.

- ^ a b c d Stewart 2009, p. 242.

- ^ Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 109.

- ^ 1900 U.S. Census – Census Place: Portland Ward 6, Multnomah, Oregon; Roll: 1350; Page: 11B; Enumeration District: 0063; FHL microfilm: 1241350

- ^ a b c Muir 2001, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 110.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 162.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Muir 2001, p. 164.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 165.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 166.

- ^ Muir 2001, pp. 166–67.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 167.

- ^ a b c Muir 2001, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e Stewart 2009, p. 243.

- ^ a b Muir 2001, p. 169.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Muir 2001, p. 171.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 14.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 41.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 44.

- ^ a b Palmer 1990, p. 40.

- ^ Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 47.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 52.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 112.

- ^ a b Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 111.

- ^ James & Wells 1992, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tucker 2009, p. 726.

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 683.

- ^ James & Wells 1992, p. 87.

- ^ Bowie & Immerman 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 670.

- ^ James & Wells 1992, p. 119.

- ^ a b Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 107.

- ^ Bowie & Immerman 2000, p. 182.

- ^ Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 113.

- OCLC 1001744417.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ Burial Detail: Radford, Arthur W (Section 30, Grave 435-LH – ANC Explorer

- ISBN 978-1480200203.

- ^ Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 106.

Sources

- Bowie, Robert R.; Immerman, Richard H. (2000), Waging Peace: How Eisenhower Shaped an Enduring Cold War Strategy, New York City: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-514048-4

- Hattendorf, John B.; Elleman, Bruce A. (2010), Nineteen-Gun Salute: Case Studies of Operational, Strategic, and Diplomatic Naval Leadership During the 20th and Early 21st Centuries, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Navy, ISBN 978-1-884733-66-6

- James, D. Clayton; Wells, Anne Sharp (1992), Refighting the Last War: Command and Crisis in Korea 1950–1953, New York City: Free Press, ISBN 978-0-02-916001-5

- Muir, Malcolm Jr. (2001), The Human Tradition in the World War II Era, Lanham, Maryland: SR Books, ISBN 978-0-8420-2786-1

- Palmer, Michael A. (1990), Origins of the Maritime Strategy: The Development of American Naval Strategy, 1945–1955, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-0-87021-667-1

- Stewart, William (2009), Admirals of the World: A Biographical Dictionary, 1500 to the Present, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-3809-9

- Tucker, Spencer (2009), U.S. Leadership in Wartime: Clashes, Controversy, and Compromise, Volume 1, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-172-5

- Lowrey, Nathan S. (2016), The Chairmanship of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1949-2016, Joint History Office, ISBN 978-1075301711

Further reading

- Radford, Arthur W.; ISBN 978-0-8179-7211-0.

External links

- Arthur W. Radford, Dictionary of Naval Fighting Ships, Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy.

- Arthur W. Radford Scrapbook, 1910–1975 (bulk 1912–1913), MS 502 held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy