Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema

| Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, palmoplantar erythrodysesthesia, hand-foot syndrome |

| |

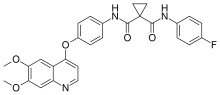

| Pictures of hands on capecitabine | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema, also known as palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia or hand-foot syndrome is reddening, swelling, numbness and

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms can occur anywhere between days to months after administration of the offending medication, depending on the dose and speed of administration.[3][4] The patient first experiences tingling and/or numbness of the palms and soles. This is followed 2-4 days later by bright redness, which is symmetrical and sharply defined.[5]

In severe cases this may be followed by burning pain and swelling, blistering and ulceration, peeling of the skin.[6] Healing occurs without scarring unless there has been skin ulceration or necrosis (skin loss/death). With each subsequent cycle of chemotherapy, the reaction will appear more quickly, be more severe and will take longer to heal.[5]

Causes

Acral erythema is a common

Pathogenesis

The cause of Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (PPE) is unknown. Existing hypotheses are based on the fact that only the hands and feet are involved and posit the role of temperature differences, vascular anatomy, differences in the types of cells (rapidly dividing epidermal cells and eccrine glands).[citation needed]

In the case of PPE caused by

Diagnosis

Painful red swelling of the hands and feet in a patient receiving chemotherapy is usually enough to make the diagnosis. The problem can also arise in patients after

Prevention

The cooling of hands and feet during chemotherapy may help prevent PPE.[3][10] Support for this and a variety of other approaches to treat or prevent acral erythema comes from small clinical studies, although none has been proven in a randomised controlled clinical trial of sufficient size.[11]

Modifying some daily activities to reduce friction and heat exposure to your hands and feet for a period of time following treatment (approximately one week after IV medication, much as possible during the time you are taking oral medication such as capecitabine)."Hand-Foot Syndrome". Chemocare. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2020-05-27.</ref>[12]

Treatment

The main treatment for acral erythema is discontinuation of the offending drug, and symptomatic treatment to provide

Symptomatic treatment can include wound care, elevation, and pain medication. Various emollients (creams) are recommended to keep skin moist. Corticosteroids and pyridoxine have also been used to relieve symptoms.[15] Other studies do not support the conclusion. A number of additional remedies are listed in recent medical literature.[16] Among them henna and 10% uridine ointment which went through clinical trial.[17]

Prognosis

Hand-foot invariably recurs with the resumption of chemotherapy. Long-term chemotherapy may also result in reversible palmoplantar keratoderma. Symptoms resolve 1–2 weeks after cessation of chemotherapy.[6] The range is 1-5 weeks, so it has recovered by the time the next cycle is due. Healing occurs without scarring unless there has been skin ulceration or necrosis. With each subsequent cycle of chemotherapy, the reaction will appear more quickly, be more severe and will take longer to heal.[5]

History

Hand-foot syndrome was first reported in association with chemotherapy by Zuehlke in 1974.[18] Synonyms for acral erythema (AE) include: hand-foot syndrome, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, peculiar AE, chemotherapy-induced AE, toxic erythema of the palms and soles, palmar-plantar erythema, and Burgdorf's reaction. Common abbreviations are HFS and PPE.

References

- ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.: 132

- PMID 21247311.

- ^ S2CID 9626443.

- S2CID 25775290.

- ^ a b c "Hand-foot syndrome". DermNet NZ.

- ^ a b Apisarnthanarax N, Duvic MM (2003). "Acral Erythema". Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (6th ed.). American Association for Cancer Research – via NCBI.

- PMID 18550575.

- S2CID 33022244.

- PMID 3527075.

- PMID 7857119.

- PMID 18331788.

- ^ "Hand-Foot Syndrome: A Side Effect of Treatment". 18 December 2020 – via breastcancer.org.

- ^ Cutaneous complications of conventional chemotherapy agents. Payne AS, Savarese DMF. In: UpToDate [Textbook of Medicine]. Massachusetts Medical Society, and Wolters Kluwer publishers. 2010.

- S2CID 22230787.

- PMID 8102408.

- S2CID 36514303.

Further reading

- Farr, Katherina Podlekareva; Safwat, Akmal (2011). "Palmar-Plantar Erythrodysesthesia Associated with Chemotherapy and Its Treatment". Case Reports in Oncology. 4 (1): 229–235. PMID 21537373.

- Hand-Foot Syndrome or Palmar-Plantar Erythrodysesthesia (1 & 2)