Crank (mechanism)

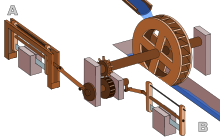

A crank is an arm attached at a right angle to a rotating shaft by which circular motion is imparted to or received from the shaft. When combined with a connecting rod, it can be used to convert circular motion into reciprocating motion, or vice versa. The arm may be a bent portion of the shaft, or a separate arm or disk attached to it. Attached to the end of the crank by a pivot is a rod, usually called a connecting rod (conrod).

The term often refers to a human-powered crank which is used to manually turn an axle, as in a

Examples

Familiar examples include:

Hand-powered cranks

- Spinning wheel

- Mechanical pencil sharpener

- Fishing reel and other reels for cables, wires, ropes, etc.

- Starting Handle for older cars

- Manually operated car window

- The carpenter's brace is a compound crank.

- The crank set that drives a handcycle through its handles.

- Hand winches

Foot-powered cranks

- The crankset that drives a bicycle via the pedals.

- Treadle sewing machine

Engines

Almost all reciprocating engines use cranks (with connecting rods) to transform the back-and-forth motion of the pistons into rotary motion. The cranks are incorporated into a crankshaft.

History

China

It was thought that evidence of the earliest true crank handle was found in a Han era glazed-earthenware tomb model of an agricultural winnowing fan dated no later than 200 AD,[3][4] but since then a series of similar pottery models with crank operated winnowing fans were unearthed, with one of them dating back to the Western Han dynasty (202 BC - 9 AD).[5][6] Historian Lynn White stated that the Chinese crank was 'not given the impulse to change reciprocating to circular motion in other contrivances', citing one reference to a Chinese crank-and-connecting rod dating to 1462.[4] However, later publications reveal that the Chinese used not just the crank, but the crank-and-connecting rod for operating querns as far back as the Western Han dynasty (202 BC - 9 AD) as well. Eventually crank-and-connecting rods were used in the inter-conversion or rotary and reciprocating motion for other applications such as flour-sifting, treadle spinning wheels, water-powered furnace bellows, and silk-reeling machines.[7][6]

Western World

Classical Antiquity

The handle of the rotary handmill which appeared in 5th century BC Celtiberian Spain and ultimately reached Greece by the first century BCE.[9][1][2][10] A Roman iron crankshaft of yet unknown purpose dating to the 2nd century AD was excavated in Augusta Raurica, Switzerland. The 82.5 cm (32.5 inches) long piece has fitted to one end a 15 cm (5.91 inches) long bronze handle, the other handle being lost.[11][8]

A ca. 40 cm (15.7 inches) long true iron crank was excavated, along with a pair of shattered mill-stones of 50 to 65 cm (19.7 to 25.6 inches) diameter and diverse iron items, in Aschheim, close to Munich. The crank-operated Roman mill is dated to the late 2nd century AD.[12] An often cited modern reconstruction of a bucket-chain pump driven by hand-cranked flywheels from the Nemi ships has been dismissed though as "archaeological fantasy".[13]

The earliest evidence for the crank combined with a connecting rod in a machine appears in the Roman

The crank and connecting rod mechanisms of the other two archaeologically attested sawmills worked without a gear train.

With the crank and connecting rod system, all elements for constructing a steam engine (invented in 1712) —

Middle Ages

A rotary

The use of crank handles in trepanation drills was depicted in the 1887 edition of the

The Italian physician Guido da Vigevano (c. 1280−1349), planning for a new crusade, made illustrations for a paddle boat and war carriages that were propelled by manually turned compound cranks and gear wheels (center of image).[24] The Luttrell Psalter, dating to around 1340, describes a grindstone which was rotated by two cranks, one at each end of its axle; the geared hand-mill, operated either with one or two cranks, appeared later in the 15th century;[25]

Medieval cranes were occasionally powered by cranks, although more often by windlasses.[26]

Renaissance

The crank became common in Europe by the early 15th century, often seen in the works of those such as the

The first depictions of the compound crank in the carpenter's brace appear between 1420 and 1430 in various northern European artwork.[29] The rapid adoption of the compound crank can be traced in the works of the Anonymous of the Hussite Wars, an unknown German engineer writing on the state of the military technology of his day: first, the connecting-rod, applied to cranks, reappeared, second, double compound cranks also began to be equipped with connecting-rods and third, the flywheel was employed for these cranks to get them over the 'dead-spot'.

One of the drawings of the Anonymous of the Hussite Wars shows a boat with a pair of paddle-wheels at each end turned by men operating compound cranks (see above). The concept was much improved by the Italian engineer and writer

In

The 15th century also saw the introduction of cranked rack-and-pinion devices, called cranequins, which were fitted to the crossbow's stock as a means of exerting even more force while spanning the missile weapon (see right).[32] In the textile industry, cranked reels for winding skeins of yarn were introduced.[25]

Around 1480, the early medieval rotary grindstone was improved with a treadle and crank mechanism. Cranks mounted on push-carts first appear in a German engraving of 1589.[33]

From the 16th century onwards, evidence of cranks and connecting rods integrated into machine design becomes abundant in the technological treatises of the period: Agostino Ramelli's The Diverse and Artifactitious Machines of 1588 alone depicts eighteen examples, a number which rises in the Theatrum Machinarum Novum by Georg Andreas Böckler to 45 different machines, one third of the total.[34]

Middle East

The crank appears in the mid-9th century in several of the hydraulic devices described by the

20th century

Cranks were formerly common on some machines in the early 20th century; for example almost all

The 1918 Reo owner's manual describes how to hand crank the automobile:

- First: Make sure the gear shifting lever is in neutral position.

- Second: The clutch pedal is unlatched and the clutch engaged. The brake pedal is pushed forward as far as possible setting brakes on the rear wheel.

- Third: See that spark control lever, which is the short lever located on top of the steering wheel on the right side, is back as far as possible toward the driver and the long lever, on top of the steering column controlling the carburetor, is pushed forward about one inch from its retarded position.

- Fourth: Turn ignition switch to point marked "B" or "M"

- Fifth: Set the carburetor control on the steering column to the point marked "START." Be sure there is gasoline in the carburetor. Test for this by pressing down on the small pin projecting from the front of the bowl until the carburetor floods. If it fails to flood it shows that the fuel is not being delivered to the carburetor properly and the motor cannot be expected to start. See instructions on page 56 for filling the vacuum tank.

- Sixth: When it is certain the carburetor has a supply of fuel, grasp the handle of starting crank, push in endwise to engage ratchet with crank shaft pin and turn over the motor by giving a quick upward pull. Never push down, because if for any reason the motor should kick back, it would endanger the operator.

Crank axle

A crank axle is a crankshaft which also serves the purpose of an axle. It is used on steam locomotives with inside cylinders.

See also

- Beam engine – Early configuration of the steam engine utilising a rocking beam to connect major components.

- Crankshaft – Mechanism for converting reciprocating motion to rotation

- Human power

- James Pickard – English inventor

- Piston motion equations

- Slider and crank mechanism

- Slider-crank linkage – Mechanism for conveting rotary motion into linear motion

- Sun and planet gear – Type of gear used in early beam engines

- Trammel of Archimedes – Ellipse-drawing mechanism

- Winch – Mechanical device that is used to adjust the tension of a rope

References

- ^ a b Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 159

- ^ a b Lucas 2005, p. 5, fn. 9

- S2CID 163331341

- ^ a b White 1962, p. 104

- ISBN 978-1-4020-9484-2.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Lisheng & Qingjun 2009, pp. 236–249.

- ^ a b Schiöler 2009, pp. 113f.

- ^ Date: Frankel 2003, pp. 17–19

- ^ A single find of a fragmentary stone dating "perhaps" to the 6th century BC may indicate a Carthaginian origin (Curtis 2008, p. 375).

- ^ Laur-Belart 1988, pp. 51–52, 56, fig. 42

- ^ Volpert 1997, pp. 195, 199

- ^ White 1962, pp. 105f.; Oleson 1984, pp. 230f.

- ^ a b c d Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 161:

Because of the findings at Ephesus and Gerasa the invention of the crank and connecting rod system has had to be redated from the 13th to the 6th c; now the Hierapolis relief takes it back another three centuries, which confirms that water-powered stone saw mills were indeed in use when Ausonius wrote his Mosella.

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 139–141

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 149–153

- ^ Mangartz 2006, pp. 579f.

- ^ Wilson 2002, p. 16

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 156, fn. 74

- ^ a b c White 1962, p. 110

- ^ Hägermann & Schneider 1997, pp. 425f.

- ^ a b White 1962, p. 170

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Hall 1979, p. 80

- ^ a b c d White 1962, p. 111

- ^ Hall 1979, p. 48

- ^ White 1962, pp. 105, 111, 168

- ^ White 1962, p. 167; Hall 1979, p. 52

- ^ White 1962, p. 112

- ^ White 1962, p. 114

- ^ a b White 1962, p. 113

- ^ Hall 1979, pp. 74f.

- ^ White 1962, p. 167

- ^ White 1962, p. 172

- ISBN 0-521-32763-6)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ al-Hassan & Hill 1992, pp. 45, 61

- ISBN 90-277-0833-9

- .

- ISBN 978-1-4358-5066-8

Bibliography

- Curtis, Robert I. (2008). "Food Processing and Preparation". In Oleson, John Peter (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World. Oxford: ISBN 978-0-19-518731-1.

- Frankel, Rafael (2003), "The Olynthus Mill, Its Origin, and Diffusion: Typology and Distribution", S2CID 192167193

- Hall, Bert S. (1979), The Technological Illustrations of the So-Called "Anonymous of the Hussite Wars". Codex Latinus Monacensis 197, Part 1, Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, ISBN 3-920153-93-6

- Hägermann, Dieter; Schneider, Helmuth (1997), Propyläen Technikgeschichte. Landbau und Handwerk, 750 v. Chr. bis 1000 n. Chr. (2nd ed.), Berlin, ISBN 3-549-05632-X)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 0-521-42239-6

- Lucas, Adam Robert (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", Technology and Culture, 46 (1): 1–30, S2CID 109564224

- Laur-Belart, Rudolf (1988), Führer durch Augusta Raurica (5th ed.), Augst

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mangartz, Fritz (2006), "Zur Rekonstruktion der wassergetriebenen byzantinischen Steinsägemaschine von Ephesos, Türkei. Vorbericht", Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 36 (1): 573–590

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology: Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-05803-1.

- ISBN 90-277-1693-5

- Volpert, Hans-Peter (1997), "Eine römische Kurbelmühle aus Aschheim, Lkr. München", Bericht der Bayerischen Bodendenkmalpflege, 38: 193–199, ISBN 3-7749-2903-3

- White, Lynn Jr. (1962), Medieval Technology and Social Change, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press

- Ritti, Tullia; Grewe, Klaus; Kessener, Paul (2007), "A Relief of a Water-powered Stone Saw Mill on a Sarcophagus at Hierapolis and its Implications", Journal of Roman Archaeology, 20: 138–163, S2CID 161937987

- Schiöler, Thorkild (2009), "Die Kurbelwelle von Augst und die römische Steinsägemühle", Helvetia Archaeologica, vol. 40, no. 159/160, pp. 113–124

- The Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 92, pp. 1–32

External links

- Crank highlight: Hypervideo of construction and operation of a four cylinder internal combustion engine courtesy of Ford Motor Company

- Kinematic Models for Design Digital Library (KMODDL) - Movies and photos of hundreds of working mechanical-systems models at Cornell University. Also includes an e-book library of classic texts on mechanical design and engineering.