Creeping vole

| Creeping vole | |

|---|---|

| |

| Microtus oregoni photographed at Wind River Experimental Forest | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Cricetidae |

| Subfamily: | Arvicolinae |

| Genus: | Microtus |

| Subgenus: | Pitymys |

| Species: | M. oregoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| Microtus oregoni (Bachman, 1839)

| |

| |

| Distribution of the creeping vole | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

List

| |

The creeping vole (Microtus oregoni), sometimes known as the Oregon meadow mouse, is a small rodent in the family Cricetidae. Ranging across the Pacific Northwest of North America, it is found in forests, grasslands, woodlands, and chaparral environments. The small-tailed, furry, brownish-gray mammal was first described in the scientific literature in 1839, from a specimen collected near the mouth of the Columbia River. The smallest vole in its range, it weighs around 19 g (11⁄16 oz). At birth, they weigh 1.6 g (1⁄16 oz), are naked, pink, unable to open their eyes, and the ear flaps completely cover the ear openings. Although not always common throughout their range, there are no major concerns for their survival as a species.

Taxonomy

The animal was described in 1839 by

Description

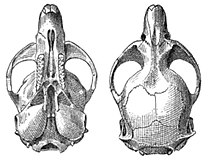

| Skull dimensions[5] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | |

| Basal length | 20.9 mm (0.82 in) | 23.4 mm (0.92 in) |

| Nasal length | 6.7 mm (0.26 in) | 7.3 mm (0.29 in) |

| Zygomatic breadth | 14 mm (0.55 in) | 14.9 mm (0.59 in) |

| Mastoid breadth | 11 mm (0.43 in) | 12.6 mm (0.50 in) |

| Upper molar alveolus | 5.5 mm (0.22 in) | 6.1 mm (0.24 in) |

On average, creeping voles weigh around 19 g (11⁄16 oz) with a reported range of 14.5 to 27.5 g (1⁄2 to 1 oz)

They are

The fur markings are plumbeous to a dark brown or black.[5] There are sometimes yellowish hair markings as well.[5] The underside fur markings tend to be lighter beige to whitish.[5] The tail may be gray to black and often lighter below.[5]

Creeping voles have a relatively short tail, measuring less than 30% their total body length.

The skull of the creeping vole has a low, flat profile, with a long and slender snout.

Distribution and habitat

Creeping voles are found in

They are found in coniferous forests and woodlands, grasslands, and chaparral.[2]

They are found at sea level through altitudes of nearly 2,400 m (7,900 ft).

It is suspected that ancestral voles migrated from Eurasia 1.2 million years ago.[5] However, no Pleistocene-era fossils of creeping voles have been identified.[5]

Behavior and ecology

Creeping voles establish nests of dry grass in protected areas, such as under logs.[1] The breeding season varies by latitude, but is mainly March to September in Oregon and British Columbia.[1] Gestation lasts around 23 days. Each litter bears three to four young and the females may produce four or five litters a year.[1] The naked, pink newborn young weigh around 1.6 g (1⁄16 oz).[11] Their eyes are closed and skin flaps cover the ear openings.[11]

Creeping voles are primarily nocturnal, though they are sometimes active during the day.[1] They are herbivorous, probably eating forbs and grasses, as well as fungi.[1]

Genetics

Creeping vole females have XO sex chromosomes, while males have XY. Evolutionary geneticists have investigated these sex chromosomal features of creeping voles. A models for the evolution of creeping vole sex chromosomes was published by researchers from the University of Edinburgh in 2001.[12] Recently, it was discovered the Y chromosome has been lost, the male-determining chromosome is a second X that is largely homologous to the female X, and both the maternally inherited and male-specific sex chromosomes carry vestiges of the ancestral Y. This is quite unusual in mammals, as the XY system is fairly stable across a number of mammal species.[13]

Conservation status

Although it is not widely distributed and not always common, the creeping vole is listed as "Least Concern" by the IUCN Red List.[1] The justifications for the listing are the lack of major threats, the stability of populations, and the adaptability of the animal to environmental changes.[1] Treatment of Douglas-fir plantations with herbicides in British Columbia did not affect creeping vole populations.[1] No conservation concerns are raised, since there are thought to be sufficient areas of protected habitat within its range.[1] NatureServe lists the species as secure within its range.[2]

References

Footnotes:

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k IUCN Red List 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g NatureServe 2016.

- ^ a b Musser & Carleton 2005.

- ^ a b c d Bachman 1839, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Verts & Carraway 1985, p. 1.

- ^ Miller 1896, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Miller 1896, p. 22.

- ^ "Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 1874, Volume 26, Page 198 | Document Viewer". Archived from the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

- ^ Miller 1896, pp. 60–62.

- ^ "Mammal Diversity Database (Version 1.11) [Data set]". Mammal Diversity Database. 2023.

- ^ a b Verts & Carraway 1985, p. 2.

- ^ Charlesworth & Dempsey 2001.

- S2CID 233872862.

Sources:

- Bachman, John (1839). "Description of several new species of American quadruped". Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 8 (60): 57–74. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Charlesworth, B.; Dempsey, N. D. (April 2001). "A model of the evolution of the unusual sex chromosome system of Microtus oregoni". Heredity. 86 (4): 387–394. PMID 11520338.

- Cassola, F. (2017) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Microtus oregoni". .

- Miller, Gerrit S. (23 July 1896). "The genera and subgenera of voles and lemmings". North American Fauna. 12: 1–85. .

- "Comprehensive Report Species – Microtus oregoni". NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life. 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- OCLC 62265494.

- Verts, B. J.; Carraway, Leslie N. (24 May 1985). "Microtus oregoni" (PDF). Mammalian Species (233): 1–6. JSTOR 3503854. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.