Crystal radio

A crystal radio receiver, also called a crystal set, is a simple

Crystal radios are the simplest type of radio receiver

The

Around 1920, crystal sets were superseded by the first amplifying receivers, which used vacuum tubes. With this technological advance, crystal sets became obsolete for commercial use[11] but continued to be built by hobbyists, youth groups, and the Boy Scouts[14] mainly as a way of learning about the technology of radio. They are still sold as educational devices, and there are groups of enthusiasts devoted to their construction.[15][16][17][18][19]

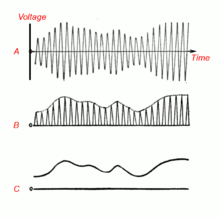

Crystal radios receive amplitude modulated (AM) signals, although FM designs have been built.[20][21] They can be designed to receive almost any radio frequency band, but most receive the AM broadcast band.[22] A few receive shortwave bands, but strong signals are required. The first crystal sets received wireless telegraphy signals broadcast by spark-gap transmitters at frequencies as low as 20 kHz.[23][24]

History

Crystal radio was invented by a long, partly obscure chain of discoveries in the late 19th century that gradually evolved into more and more practical radio receivers in the early 20th century. The earliest practical use of crystal radio was to receive Morse code radio signals transmitted from spark-gap transmitters by early amateur radio experimenters. As electronics evolved, the ability to send voice signals by radio caused a technological explosion around 1920 that evolved into today's radio broadcasting industry.

Early years

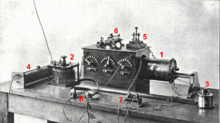

Early radio telegraphy used

In the early 20th century, various researchers discovered that certain metallic minerals, such as galena, could be used to detect radio signals.[26][27]

A crystal detector includes a crystal, usually a thin wire or metal probe that contacts the crystal, and the stand or enclosure that holds those components in place. The most common crystal used is a small piece of

1920s and 1930s

In 1922 the (then named)

In the beginning of the 20th century, radio had little commercial use, and radio experimentation was a hobby for many people.

In 1921, factory-made radios were very expensive. Since less-affluent families could not afford to own one, newspapers and magazines carried articles on how to build a crystal radio with common household items. To minimize the cost, many of the plans suggested winding the tuning coil on empty pasteboard containers such as oatmeal boxes, which became a common foundation for homemade radios.

Crystodyne

In early 1920s

A crystodyne could be produced under primitive conditions; it could be made in a rural forge, unlike vacuum tubes and modern semiconductor devices. However, this discovery was not supported by the authorities and was soon forgotten; no device was produced in mass quantity beyond a few examples for research.

"Foxhole radios"

In addition to mineral crystals, the oxide coatings of many metal surfaces act as semiconductors (detectors) capable of rectification. Crystal radios have been improvised using detectors made from rusty nails, corroded pennies, and many other common objects.

When

In some German-occupied countries during WW2 there were widespread confiscations of radio sets from the civilian population. This led determined listeners to build their own clandestine receivers which often amounted to little more than a basic crystal set. Anyone doing so risked imprisonment or even death if caught, and in most of Europe the signals from the BBC (or other allied stations) were not strong enough to be received on such a set.

"Rocket Radio"

In the late 1950s, the compact "rocket radio", shaped like a rocket, typically imported from Japan, was introduced, and gained moderate popularity.[37] It used a piezoelectric crystal earpiece (described later in this article), a ferrite core to reduce the size of the tuning coil (also described later), and a small germanium fixed diode, which did not require adjustment. To tune in stations, the user moved the rocket nosepiece, which, in turn, moved a ferrite core inside a coil, changing the inductance in a tuned circuit. Earlier crystal radios suffered from severely reduced Q, and resulting selectivity, from the electrical load of the earphone or earpiece. Furthermore, with its efficient earpiece, the "rocket radio" did not require a large antenna to gather enough signal. With much higher Q, it could typically tune in several strong local stations, while an earlier radio might only receive one station, possibly with other stations heard in the background.

For listening in areas where an electric outlet was not available, the "rocket radio" served as an alternative to the vacuum tube portable radios of the day, which required expensive and heavy batteries. Children could hide "rocket radios" under the covers, to listen to radio when their parents thought they were sleeping. Children could take the radios to public swimming pools and listen to radio when they got out of the water, clipping the ground wire to a chain link fence surrounding the pool. The rocket radio was also used as an emergency radio, because it did not require batteries or an AC outlet.

The rocket radio was available in several rocket styles, as well as other styles that featured the same basic circuit.[38]

Transistor radios had become available at the time, but were expensive. Once those radios dropped in price, the rocket radio declined in popularity.

Later years

While it never regained the popularity and general use that it enjoyed at its beginnings, the crystal radio circuit is still used. The

Building crystal radios was a

Basic principles

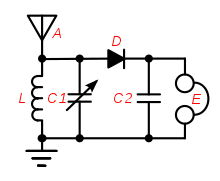

A crystal radio can be thought of as a radio receiver reduced to its essentials.[3][39] It consists of at least these components:[22][40][41]

- An antenna in which electric currents are induced by radio waves.

- A resonant frequency, and allows radio waves at that frequency to pass through to the detector while largely blocking waves at other frequencies. One or both of the coil or capacitor is adjustable, allowing the circuit to be tuned to different frequencies. In some circuits a capacitor is not used and the antenna serves this function, as an antenna that is shorter than a quarter-wavelength of the radio waves it is meant to receive is capacitive.

- A semiconductor diodes, although some hobbyists still experiment with crystal or other detectors.

- An earphone to convert the audio signal to sound waves so they can be heard. The low power produced by a crystal receiver is insufficient to power a loudspeaker, hence earphones are used.

As a crystal radio has no power supply, the sound power produced by the earphone comes solely from the

Design

Commercial passive receiver development was abandoned with the advent of reliable vacuum tubes around 1920, and subsequent crystal radio research was primarily done by

The following sections discuss the parts of a crystal radio in greater detail.Antenna

The antenna converts the energy in the electromagnetic

Serious crystal radio hobbyists use "inverted L" and

Ground

The wire antennas used with crystal receivers are

Tuned circuit

The

The circuit can be adjusted to different frequencies by varying the inductance (L), the capacitance (C), or both, "tuning" the circuit to the frequencies of different radio stations.[1] In the lowest-cost sets, the inductor was made variable via a spring contact pressing against the windings that could slide along the coil, thereby introducing a larger or smaller number of turns of the coil into the circuit, varying the inductance. Alternatively, a variable capacitor is used to tune the circuit.[69] Some modern crystal sets use a ferrite core tuning coil, in which a ferrite magnetic core is moved into and out of the coil, thereby varying the inductance by changing the magnetic permeability (this eliminated the less reliable mechanical contact).[70]

The antenna is an integral part of the tuned circuit and its

The earliest crystal receivers did not have a tuned circuit at all, and just consisted of a crystal detector connected between the antenna and ground, with an earphone across it.[1][71] Since this circuit lacked any frequency-selective elements besides the broad resonance of the antenna, it had little ability to reject unwanted stations, so all stations within a wide band of frequencies were heard in the earphone[53] (in practice the most powerful usually drowns out the others). It was used in the earliest days of radio, when only one or two stations were within a crystal set's limited range.

Impedance matching

An important principle used in crystal radio design to transfer maximum power to the earphone is impedance matching.[53][73] The maximum power is transferred from one part of a circuit to another when the impedance of one circuit is the complex conjugate of that of the other; this implies that the two circuits should have equal resistance.[1][74][75] However, in crystal sets, the impedance of the antenna-ground system (around 10–200 ohms[57]) is usually lower than the impedance of the receiver's tuned circuit (thousands of ohms at resonance),[76] and also varies depending on the quality of the ground attachment, length of the antenna, and the frequency to which the receiver is tuned.[47]

Therefore, in improved receiver circuits, in order to match the antenna impedance to the receiver's impedance, the antenna was connected across only a portion of the tuning coil's turns.[68][71] This made the tuning coil act as an impedance matching transformer (in an autotransformer connection) in addition to providing the tuning function. The antenna's low resistance was increased (transformed) by a factor equal to the square of the turns ratio (the ratio of the number of turns the antenna was connected to, to the total number of turns of the coil), to match the resistance across the tuned circuit.[75] In the "two-slider" circuit, popular during the wireless era, both the antenna and the detector circuit were attached to the coil with sliding contacts, allowing (interactive)[77] adjustment of both the resonant frequency and the turns ratio.[78][79][80] Alternatively a multiposition switch was used to select taps on the coil. These controls were adjusted until the station sounded loudest in the earphone.

Problem of selectivity

One of the drawbacks of crystal sets is that they are vulnerable to interference from stations near in frequency to the desired station.[2][4][47] Often two or more stations are heard simultaneously. This is because the simple tuned circuit does not reject nearby signals well; it allows a wide band of frequencies to pass through, that is, it has a large bandwidth (low Q factor) compared to modern receivers, giving the receiver low selectivity.[4]

The crystal detector worsened the problem, because it has relatively low

Inductive coupling

In more sophisticated crystal receivers, the tuning coil is replaced with an adjustable air core antenna coupling transformer[1][53] which improves the selectivity by a technique called loose coupling.[71][80][82] This consists of two

Reducing the coupling between the coils, by physically separating them so that less of the

One design common in early days, called a "loose coupler", consisted of a smaller secondary coil inside a larger primary coil.[53][84] The smaller coil was mounted on a rack so it could be slid linearly in or out of the larger coil. If radio interference was encountered, the smaller coil would be slid further out of the larger, loosening the coupling, narrowing the bandwidth, and thereby rejecting the interfering signal.

The antenna coupling transformer also functioned as an impedance matching transformer, that allowed a better match of the antenna impedance to the rest of the circuit. One or both of the coils usually had several taps which could be selected with a switch, allowing adjustment of the number of turns of that transformer and hence the "turns ratio".

Coupling transformers were difficult to adjust, because the three adjustments, the tuning of the primary circuit, the tuning of the secondary circuit, and the coupling of the coils, were all interactive, and changing one affected the others.[85]

Crystal detector

The crystal

Only certain sites on the crystal surface functioned as rectifying junctions, and the device was very sensitive to the pressure of the crystal-wire contact, which could be disrupted by the slightest vibration.[6][92] Therefore, a usable contact point had to be found by trial and error before each use. The operator dragged the wire across the crystal surface until a radio station or "static" sounds were heard in the earphones.[93] Alternatively, some radios (circuit, right) used a battery-powered buzzer attached to the input circuit to adjust the detector.[93] The spark at the buzzer's electrical contacts served as a weak source of static, so when the detector began working, the buzzing could be heard in the earphones. The buzzer was then turned off, and the radio tuned to the desired station.

In modern sets, a

All semiconductor detectors function rather inefficiently in crystal receivers, because the low voltage input to the detector is too low to result in much difference between forward better conduction direction, and the reverse weaker conduction. To improve the sensitivity of some of the early crystal detectors, such as silicon carbide, a small

Earphones

The requirements for earphones used in crystal sets are different from earphones used with modern audio equipment. They have to be efficient at converting the electrical signal energy to sound waves, while most modern earphones sacrifice efficiency in order to gain high fidelity reproduction of the sound.[104] In early homebuilt sets, the earphones were the most costly component.[105]

The early earphones used with wireless-era crystal sets had moving iron drivers that worked in a way similar to the horn loudspeakers of the period. Each earpiece contained a permanent magnet about which was a coil of wire which formed a second electromagnet. Both magnetic poles were close to a steel diaphragm of the speaker. When the audio signal from the radio was passed through the electromagnet's windings, current was caused to flow in the coil which created a varying magnetic field that augmented or diminished that due to the permanent magnet. This varied the force of attraction on the diaphragm, causing it to vibrate. The vibrations of the diaphragm push and pull on the air in front of it, creating sound waves. Standard headphones used in telephone work had a low impedance, often 75 Ω, and required more current than a crystal radio could supply. Therefore, the type used with crystal set radios (and other sensitive equipment) was wound with more turns of finer wire giving it a high impedance of 2000–8000 Ω.[106][107][108]

Modern crystal sets use

Although the low power produced by crystal radios is typically insufficient to drive a loudspeaker, some homemade 1960s sets have used one, with an audio transformer to match the low impedance of the speaker to the circuit.[111] Similarly, modern low-impedance (8 Ω) earphones cannot be used unmodified in crystal sets because the receiver does not produce enough current to drive them. They are sometimes used by adding an audio transformer to match their impedance with the higher impedance of the driving antenna circuit.

Use as a power source

A crystal radio tuned to a strong local transmitter can be used as a power source for a second amplified receiver of a distant station that cannot be heard without amplification.[112]: 122–123

There is a long history of unsuccessful attempts and unverified claims to recover the power in the carrier of the received signal itself. Conventional crystal sets use half-wave rectifiers. As AM signals have a modulation factor of only 30% by voltage at peaks[citation needed], no more than 9% of received signal power () is actual audio information, and 91% is just rectified DC voltage. <correction> The 30% figure is the standard used for radio testing, and is based on the average modulation factor for speech. Properly-designed and managed AM transmitters can be run to 100% modulation on peaks without causing distortion or "splatter" (excess sideband energy that radiates outside of the intended signal bandwidth). Given that the audio signal is unlikely to be at peak all the time, the ratio of energy is, in practice, even greater. Considerable effort was made to convert this DC voltage into sound energy. Some earlier attempts include a one-transistor[113] amplifier in 1966. Sometimes efforts to recover this power are confused with other efforts to produce a more efficient detection.[114] This history continues now with designs as elaborate as "inverted two-wave switching power unit".[112]: 129

Gallery

See also

- Batteryless radio

- Camille Papin Tissot

- Coherer

- Demodulator

- Detector (radio)

- Electrolytic detector

- History of radio

References

- ^ ISBN 0-8306-3342-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-148929-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55652-520-9.

- ^ ISBN 0-7923-8518-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-28903-0.

- ^ ISBN 0-393-31851-6.

- ISBN 0-471-71814-9.

- ISBN 9780986488511. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ^ Sarkar (2006) History of wireless, pp. 94, 291–308

- ^ ISBN 0-521-29681-1.

- S2CID 51644366. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ISBN 1-4208-9084-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55652-774-6.

- ^ Jack Bryant (2009) Birmingham Crystal Radio Group, Birmingham, Alabama, US. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ The Xtal Set Society midnightscience.com . Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Darryl Boyd (2006) Stay Tuned Crystal Radio website. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Al Klase Crystal Radios, Klase's SkyWaves website . Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Mike Tuggle (2003) Designing a DX crystal set Archived 2010-01-24 at the Wayback Machine Antique Wireless Association Archived 2010-05-23 at the Wayback Machine journal. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Solomon, Larry J. (2007-12-30). "FM Crystal Radios". Archived from the original on 2007-12-30. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ISBN 978-0-07-148929-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84728-526-3.

- ^ Lescarboura, Austin C. (1922). Radio for Everybody. New York: Scientific American Publishing Co. pp. 4, 110, 268.

- ^ Long distance transoceanic stations of the era used wavelengths of 10,000 to 20,000 meters, correstponding to frequencies of 15 to 30 kHz.Morecroft, John H.; A. Pinto; Walter A. Curry (1921). Principles of Radio Communication. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 187.

- ^ "Construction and Operation of a Simple Homemade Radio Receiving Outfit, Bureau of Standards Circular 120". U.S. Government Printing Office. April 24, 1922.

- ^ In May 1901, Karl Ferdinand Braun of Strasbourg used psilomelane, a manganese oxide ore, as an R.F. detector: Ferdinand Braun (December 27, 1906) "Ein neuer Wellenanzeiger (Unipolar-Detektor)" (A new R.F. detector (one-way detector)), Elektrotechnische Zeitschrift, 27 (52) : 1199–1200. From p. 1119:

"Im Mai 1901 habe ich einige Versuche im Laboratorium gemacht und dabei gefunden, daß in der Tat ein Fernhörer, der in einen aus Psilomelan und Elementen bestehenden Kreis eingeschaltet war, deutliche und scharfe Laute gab, wenn dem Kreise schwache schnelle Schwingungen zugeführt wurden. Das Ergebnis wurde nachgeprüft, und zwar mit überraschend gutem Erfolg, an den Stationen für drahtlose Telegraphie, an welchen zu dieser Zeit auf den Straßburger Forts von der Königlichen Preußischen Luftschiffer-Abteilung unter Leitung des Hauptmannes von Sigsfeld gearbeitet wurde."

(In May 1901, I did some experiments in the lab and thereby found that in fact an earphone, which was connected in a circuit consisting of psilomelane and batteries, produced clear and strong sounds when weak, rapid oscillations were introduced to the circuit. The result was verified – and indeed with surprising success – at the stations for wireless telegraphy, which, at this time, were operated at the Strasbourg forts by the Royal Prussian Airship-Department under the direction of Capt. von Sigsfeld.)

Braun also states that he had been researching the conductive properties of semiconductors since 1874. See: Braun, F. (1874) "Ueber die Stromleitung durch Schwefelmetalle" (On current conduction through metal sulfides), Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 153 (4) : 556–563. In these experiments, Braun applied a cat whisker to various semiconducting crystals and observed that current flowed in only one direction.

Braun patented an R.F. detector in 1906. See: (Ferdinand Braun), "Wellenempfindliche Kontaktstelle" (R.F. sensitive contact), Deutsches Reichspatent DE 178,871, (filed: Feb. 18, 1906 ; issued: Oct. 22, 1906). Available on-line at: Foundation for German communication and related technologies - ^ Other inventors who patented crystal R.F. detectors:

- In 1906, Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody (1843–1933) of Washington, D.C., a retired general of the US Army's Signal Corps, received a patent for a carborundum R.F. detector. See: Dunwoody, Henry H. C. "Wireless-telegraph system," U. S. patent 837,616 (filed: March 23, 1906 ; issued: December 4, 1906).

- In 1907, Louis Winslow Austin received a patent for his R.F. detector consisting of tellurium and silicon. See: Louis W. Austin, "Receiver," US patent 846,081 (filed: Oct. 27, 1906 ; issued: March 5, 1907).

- In 1908, Wichi Torikata of the Imperial Japanese Electrotechnical Laboratory of the Ministry of Communications in Tokyo was granted Japanese patent 15,345 for the “Koseki” detector, consisting of crystals of zincite and bornite.

- ISBN 978-0986488511. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ^ Jagadis Chunder Bose, "Detector for electrical disturbances", US patent no. 755,840 (filed: September 30, 1901; issued: March 29, 1904)

- ^ Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, "Means for receiving intelligence communicated by electric waves", US patent no. 836,531 (filed: August 30, 1906 ; issued: November 20, 1905)

- ^ http://www.crystalradio.net/crystalplans/xximages/nsb_120.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ http://www.crystalradio.net/crystalplans/xximages/nbs121.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Bondi, Victor."American Decades: 1930–1939"

- ISBN 0-86341-227-0, p. 15

- ^ "The Crystodyne Principle", Radio News, September 1924, pp. 294–295, 431.

- ^ In 1924, Losev's (also spelled "Lossev" and "Lossew") research was publicized in several French publications:

- Radio Revue, no. 28, p. 139 (1924)

- I. Podliasky (May 25, 1924) (Crystal detectors as oscillators), Radio Électricité, 5 : 196–197.

- M. Vingradow (September 1924) "Lés Détecteurs Générateurs", pp. 433–448, L'Onde Electrique

- Hugh S. Pocock (June 11, 1924) "Oscillating and Amplifying Crystals", The Wireless World and Radio Review, 14: 299–300.

- Victor Gabel (October 1 & 8, 1924) "The crystal as a generator and amplifier," The Wireless World and Radio Review, 15 : 2ff, 47ff.

- O. Lossev (October 1924) "Oscillating crystals," The Wireless World and Radio Review, 15 : 93–96.

- Round and Rust (August 19, 1925) The Wireless World and Radio Review, pp. 217–218.

- "The Crystodyne principle", Radio News, pp. 294–295, 431 (September 1924). See also the October 1924 issue of Radio News. (It was Hugo Gernsback, publisher of Radio News, who coined the term "crystodyne".)

- ^ Rocket Crystal Radio

- ^ 1950s Crystal Radios

- ^ Purdie, Ian C. (2001). "Crystal Radio Set". electronics-tutorials.com. Ian Purdie. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ^ Lescarboura, Austin C. (1922). Radio for Everybody. New York: Scientific American Publishing Co. pp. 93–94.

- ^ Kuhn, Kenneth A. (Jan 6, 2008). "Introduction" (PDF). Crystal Radio Engineering. Prof. Kenneth Kuhn website, Univ. of Alabama. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ H. C. Torrey, C. A. Whitmer, Crystal Rectifiers, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1948, pp. 3–4

- ISBN 1922013846.

- ^ a b Morgan, Alfred Powell (1914). Wireless Telegraph Construction for Amateurs, 3rd Ed. D. Van Nostrand Co. p. 199.

- ISBN 0521289033.

- ^ Fette, Bruce A. (Dec 27, 2008). "RF Basics: Radio Propagation". RF Engineer Network. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ a b c d Payor, Steve (June 1989). "Build a Matchbox Crystal Radio". Popular Electronics: 42. Retrieved 2010-05-28. on Stay Tuned website

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-83526-8.

- ^ Nave, C. Rod. "Threshold of hearing". HyperPhysics. Dept. of Physics, Georgia State University. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ Lescarboura, 1922, p. 144

- ^ a b c Binns, Jack (November 1922). "Jack Binn's 10 commandments for the radio fan". Popular Science. 101 (5). New York: Modern Publishing Co.: 42–43. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ISBN 0852967926.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Klase, Alan R. (1998). "Crystal Set Design 102". Skywaves. Alan Klase personal website. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ a list of circuits from the wireless era can be found in Sleeper, Milton Blake (1922). Radio hook-ups: a reference and record book of circuits used for connecting wireless instruments. US: The Norman W. Henley publishing co. pp. 7–18.

- ^ May, Walter J. (1954). The Boy's Book of Crystal Sets. London: Bernard's. is a collection of 12 circuits

- ^ Purdie, Ian (1999). "A Basic Crystal Set". Ian Purdie's Amateur Radio Pages. personal website. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ^ a b c d Kuhn, Kenneth (Dec 9, 2007). "Antenna and Ground System" (PDF). Crystal Radio Engineering. Kenneth Kuhn website, Univ. of Alabama. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Marx, Harry J.; Adrian Van Muffling (1922). Radio Reception: A simple and complete explanation of the principles of radio telephony. US: G.P. Putnam's sons. pp. 130–131.

- ^ Williams, Henry Smith (1922). Practical Radio. New York: Funk and Wagnalls. p. 58.

- ^ Putnam, Robert (October 1922). "Make the aerial a good one". Tractor and Gas Engine Review. 15 (10). New York: Clarke Publishing Co.: 9. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Lescarboura 1922, p. 100

- ISBN 1-60680-119-8.

- ^ Lescarboura, 1922, pp. 102–104

- ^ Radio Communication Pamphlet No. 40: The Principles Underlying Radio Communication, 2nd Ed. United States Bureau of Standards. 1922. pp. 309–311.

- ISBN 1-110-37159-4.

- ^ Hausmann, Goldsmith & Hazeltine 1922, p. 48

- ISBN 978-0-07-027382-5.

- ^ a b Kuhn, Kenneth A. (Jan 6, 2008). "Resonant Circuit" (PDF). Crystal Radio Engineering. Prof. Kenneth Kuhn website, Univ. of Alabama. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Clifford, Martin (July 1986). "The early days of radio". Radio Electronics: 61–64. Retrieved 2010-07-19. on Stay Tuned website

- ^ Blanchard, T. A. (October 1962). "Vestpocket Crystal Radio". Radio-Electronics: 196. Retrieved 2010-08-19. on Crystal Radios and Plans, Stay Tuned website

- ^ a b c d e f The Principles Underlying Radio Communication, 2nd Ed., Radio pamphlet no. 40. US: Prepared by US National Bureau of Standards, United States Army Signal Corps. 1922. pp. 421–425.

- ^ Hausmann, Goldsmith & Hazeltine 1922, p. 57

- ISBN 0-387-95150-4.

- ISBN 0-521-37769-2.

- ^ ISBN 0-471-02450-3.

- ^ Tongue, Ben H. (2007-11-06). "Practical considerations, helpful definitions of terms and useful explanations of some concepts used in this site". Crystal Radio Set Systems: Design, Measurement, and Improvement. Ben Tongue. Archived from the original on 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Bucher, Elmer Eustace (1921). Practical Wireless Telegraphy: A complete text book for students of radio communication (Revised ed.). New York: Wireless Press, Inc. p. 133.

- ^ Marx & Van Muffling (1922) Radio Reception, p. 94

- ^ Stanley, Rupert (1919). Textbook on Wireless Telegraphy, Vol. 1. London: Longman's Green & Co. pp. 280–281.

- ^ ISBN 1-60680-119-8.

- ^ a b c d Wenzel, Charles (1995). "Simple crystal radio". Crystal radio circuits. techlib.com. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Hogan, John V. L. (October 1922). "The Selective Double-Circuit Receiver". Radio Broadcast. 1 (6). New York: Doubleday Page & Co.: 480–483. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- ^ Alley & Atwood (1973) Electronic Engineering, p. 318

- ^ Marx & Van Muffling (1922) Radio Reception, pp. 96–101

- ^ US Signal Corps (October 1916). Radiotelegraphy. US: Government Printing Office. p. 70.

- ^ Marx & Van Muffling (1922) Radio Reception, p. 43, fig. 22

- ^ a b Campbell, John W. (October 1944). "Radio Detectors and How They Work". Popular Science. 145 (4). New York: Popular Science Publishing Co.: 206–209. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ H. V. Johnson, A Vacation Radio Pocket Set. Electrical Experimenter, vol. II, no. 3, p. 42, Jul. 1914

- ^ "The cat's-whisker detector is a primitive point-contact diode. A point-contact junction is the simplest implementation of a Schottky diode, which is a majority-carrier device formed by a metal-semiconductor junction." Shaw, Riley (April 2015). "The cat's-whisker detector". Riley Shaw's personal blog. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ISBN 0-521-83539-9.

- ^ Stanley (1919) Text-book on Wireless Telegraphy, p. 282

- ^ a b Hausmann, Goldsmith & Hazeltine 1922, pp. 60–61

- ^ a b Lescarboura (1922), pp. 143–146

- ^ Hirsch, William Crawford (June 1922). "Radio Apparatus – What is it made of?". The Electrical Record. 31 (6). New York: The Gage Publishing Co.: 393–394. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Stanley (1919), pp. 311–318

- ^ Gernsback, Hugo (September 1944). "Foxhole emergency radios". Radio-Craft. 16 (1). New York: Radcraft Publications: 730. Retrieved 2010-03-14. on Crystal Plans and Circuits, Stay Tuned website

- S2CID 44288637. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Kuhn, Kenneth A. (Jan 6, 2008). "Diode Detectors" (PDF). Crystal Radio Engineering. Prof. Kenneth Kuhn website, Univ. of Alabama. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Hadgraft, Peter. "The Crystal Set 5/6". The Crystal Corner. Kev's Vintage Radio and Hi-Fi page. Archived from the original on 2010-07-20. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ Kleijer, Dick. "Diodes". crystal-radio.eu. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ^ The Principles Underlying Radio Communication (1922), p.439-440

- ^ "The sensitivity of the Perikon [detector] can be approximately doubled by connecting a battery across its terminals to give approximately 0.2 volt" Robison, Samuel Shelburne (1911). Manual of Wireless Telegraphy for the Use of Naval Electricians, Vol. 2. Washington DC: US Naval Institute. p. 131.

- ^ "Certain crystals if this combination [zincite-bornite] respond better with a local battery while others do not require it...but with practically any crystal it aids in obtaining the sensitive adjustment to employ a local battery..."Bucher, Elmer Eustace (1921). Practical Wireless Telegraphy: A complete text book for students of radio communication, Revised Ed. New York: Wireless Press, Inc. pp. 134–135, 140.

- ^ a b Field 2003, pp. 93–94

- ^ Lescarboura (1922), p. 285

- ^ Collins (1922), pp. 27–28

- ^ Williams (1922), p. 79

- ^ The Principles Underlying Radio Communication (1922), p. 441

- ^ Payor, Steve (June 1989). "Build a Matchbox Crystal Radio". Popular Electronics: 45. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ Field (2003), p. 94

- ^ Walter B. Ford, "High Power Crystal Set", August 1960, Popular Electronics

- ^ ISBN 5-94074-056-1.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ Radio-Electronics, 1966, №2

- ^ Cutler, Bob (January 2007). "High Sensitivity Crystal Set" (PDF). QST. 91 (1): 31–??.

Further reading

- Ellery W. Stone (1919). Elements of Radiotelegraphy. D. Van Nostrand company. 267 pages.

- Elmer Eustice Bucher (1920). The Wireless Experimenter's Manual: Incorporating how to Conduct a Radio Club.

- Milton Blake Sleeper (1922). Radio Hook-ups: A Reference and Record Book of Circuits Used for Connecting Wireless Instruments. The Norman W. Henley publishing co.; 67 pages.

- JL Preston and HA Wheeler (1922) "Construction and operation of a simple homemade radio receiving outfit", Bureau of Standards, C-120: Apr. 24, 1922.

- PA Kinzie (1996). Crystal Radio: History, Fundamentals, and Design. Xtal Set Society.

- Thomas H. Lee (2004). The Design of CMOS Radio-Frequency Integrated Circuits

- Derek K. Shaeffer and Thomas H. Lee (1999). The Design and Implementation of Low-Power CMOS Radio Receivers

- Ian L. Sanders. Tickling the Crystal – Domestic British Crystal Sets of the 1920s; Volumes 1–5. BVWS Books (2000–2010).

External links

- A website with lots of information on early radio and crystal sets

- Hobbydyne Crystal Radios History and Technical Information on Crystal Radios

- Ben Tongue's Technical Talk Section 1 links to "Crystal Radio Set Systems: Design, Measurements and Improvement".

- "Semiconductor archeology or tribute to unknown precursors Archived 2013-03-17 at the Wayback Machine". earthlink.net/~lenyr.

- Nyle Steiner K7NS, Zinc Negative Resistance RF Amplifier for Crystal Sets and Regenerative Receivers Uses No Tubes or Transistors. November 20, 2002.

- Crystal Set DX? Roger Lapthorn G3XBM

- Details of crystals used in crystal sets

- Asquin, Don; Rabjohn, Gord (April 2012). "High Performance Crystal Radios" (PDF). Ottawa Electronics Club. Retrieved 2016-09-27.

- http://www.crystal-radio.eu/endiodes.htm Diodes

- http://www.crystal-radio.eu/engev.htm How to build a sensitive crystal receiver?

- http://uv201.com/Radio_Pages/Pre-1921/crystal_detectors.htm Crystal Detectors

- http://www.sparkmuseum.com/DETECTOR.HTM Radio Detectors

- The Crystal Set Perfected