HMS Beaulieu

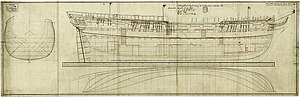

1790 diagram of Beaulieu

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Beaulieu |

| Namesake | Edward Hussey-Montagu, 1st Earl Beaulieu |

| Laid down | 1790 |

| Launched | 4 May 1791 |

| Completed | 31 May 1791 |

| Acquired | Purchased 16 June 1790 |

| Commissioned | January 1793 |

| Out of service | March/April 1806 |

| Nickname(s) | Bowly |

| Fate | Broken up 1809 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 1,01979⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 39 ft 6 in (12 m) |

| Draught |

|

| Depth of hold | 15 ft 2+5⁄8 in (4.6 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Complement | 280 (274 from 1794) |

| Armament |

|

HMS Beaulieu (

In 1797 Beaulieu joined the

Beaulieu was put

Design and construction

HMS Beaulieu was a 40-gun,

Beaulieu was laid down some time in the first half of 1790, and was purchased by the Royal Navy on 16 June mid-way through construction, after an

Beaulieu was launched by

While the ship was fitted out to Royal Navy standards after her purchase, the initial design had been down to Adams. As such, Beaulieu was not built in the slim fashion of other frigates, and was instead closer in proportion to a merchant ship of the period. This meant that her hold space was much greater than the average frigate, providing the capacity to store around double the amount of drinking water and ballast.[a] While no official report on Beaulieu's sailing survives, her unusual proportions have led the naval historian Robert Gardiner to suggest that it is "unlikely she was much of a sailer".[9]

Beaulieu held forty long guns.[10] The ship was internally laid out in the standard fashion for a 38-gun frigate, but with the addition of two extra gun ports.[9] Twenty-eight 18-pounders were held on the upper deck, with eight 9-pounders on the quarterdeck and a further four on the forecastle.[10] On 20 February 1793 an Admiralty Order had Beaulieu take on a number of carronades, with two 32-pounders on the upper deck and six 18-pounders on the quarterdeck. On 29 December six of the carronades were replaced with newer models, but they were all removed from the ship later on.[10][16] Beaulieu's upper deck had fifteen gun ports on each side, but only fourteen of these were ever put into regular use, with the final pair briefly holding the 1793 carronades but otherwise being left empty.[3]

The ship was designed with a crew complement of 280. On 12 December 1794 the Admiralty reorganised ship complements, taking into account the increased use of carronades, and Beaulieu's was lowered to 274 men.[10][17] This was because carronades were lighter than long guns and required a smaller gun crew to operate.[18] Many captains found this decrease unacceptable and frigate crews were often bolstered, although this is not recorded in Beaulieu's case.[17]

Service

West Indies

Beaulieu was

Jervis was undertaking a campaign to capture the valuable French-held islands in the West Indies, which accounted for a third of all French trade and supported (directly or indirectly) a fifth of the population.

Beaulieu continued on with the expedition which arrived off

On 2 December the frigate captured a fast-sailing French 10-gun

Riou was invalided home and replaced by Captain

Beaulieu arrived at the aftermath of an inconclusive duel between the 32-gun frigate HMS Mermaid and the French 40-gun frigate Vengeance off Basseterre on 8 August. Her presence forced the French vessel to disengage and retreat to safety under the guns of a battery in Basseterre Roads.[10][37] Towards the end of the year Beaulieu returned to Britain, carrying as passengers Rear-Admiral Sir Hugh Christian, who had been replaced as commander-in-chief of the Leeward Islands, and Rear-Admiral Charles Pole.[38][39]

Nore mutiny

Beaulieu received a refit at

Beaulieu was serving as a

Having sailed from the Nore, despite the authorities removing the marker buoys to make navigation out of the anchorage more difficult, off Margate on 11 June the mutinous members of Beaulieu were overpowered. Five escaped in a cutter but were caught when they landed in Kent on the following day. Five were also arrested on 15 June for having served as delegates of the crew during the mutiny.[45] The Admiralty pardoned all of the crew, bar the men arrested.[50] Soon after this Captain Francis Fayerman assumed command.[51]

In the aftermath two men remained imprisoned in the ship, and in order to release them the crew mutinied again on 25 June under Redhead.[52][51] He announced that his aim was "to turn every bastard of an officer on shore, and if any of the seamen were not true to the cause to hang them immediately".[53] Fayerman was on shore, and so Lieutenant John Burn received their demands for the release of the two men. Burn refused, and at 9 p.m. the men went to forcibly release their colleagues.[51] Burn armed his officers and marines and met the mutineers; after refusing a request to go back to bed, one of them ran at Burn with a cutlass. He was shot in the neck by the ship's purser and in the body by Burn.[54]

The mutineers made a second attempt to attack the officers and marines, stabbing one of them and attempting to gain control of more cutlasses. The defenders shot at them again, hitting two, and the survivors ran to Beaulieu's forecastle where they started turning her 9-pounders around to point back into the ship. Before they could fire Burn caught up with them again and all but one, who he shot in the shoulder, ran off. Burn then returned to the quarterdeck where he was attacked by one more mutineer, bruising his stomach with a cutlass. By 10:30 p.m. the mutiny had been quelled, and thirteen mutineers arrested. Thirteen men in total were wounded in the fight, of which at least one, the man shot by Burn and the purser, died.[54]

The loyal members of Beaulieu's crew were assisted in the fight by the 40-gun frigate

Camperdown

News reached Duncan on 9 October that the French-aligned Dutch fleet was at sea, and his fleet sailed from

As the battle ended Beaulieu sailed up to the Dutch 44-gun frigate Monnikkendam, which surrendered to her.[70] A prize crew was put on board for the journey back to Britain under the command of Lieutenant James Robert Philips. While making this journey the frigate was wrecked on sands off West Capel.[71][72] Philips and his crew survived, but were all taken as prisoners of war.[72] After the battle bad sea conditions meant that many damaged warships were struggling to stay away from the shore, and Beaulieu was sent by Duncan to search out and assist any distressed ships that she could find.[68]

The 40-gun frigate HMS Endymion had joined the fleet after the battle, and on 12 October discovered the Dutch 74-gun ship of the line Brutus, which had escaped the battle, close to shore. Endymion attempted to attack her but with the Dutch ship well-positioned close to the coastline and the tide pulling Endymion into the line of her broadside, she chose to look for assistance. Endymion sailed back towards Duncan's fleet firing rockets to attract attention, and at 10:30 p.m. on 13 October these were spotted by Beaulieu.[73][71] Together the frigates returned to Brutus, arriving at 5 a.m. on the following day.[74] The two frigates chased the ship of the line, but she succeeded in reaching the safety of the port of Goree before they were able to engage her; Brutus was one of seven ships of the line to escape Camperdown.[73] Beaulieu was sent out again by Duncan to assist damaged ships on 15 October, in company with the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Lancaster.[75]

Having completed these duties, Beaulieu was subsequently sent to join a squadron commanded by Captain Sir Richard Strachan in 1798.[10] Strachan's squadron was employed in patrolling the coasts of Normandy and Brittany.[76] When the Irish Rebellion of 1798 began fears grew amongst officers that sailors would again take the opportunity to mutiny, and for a period officers in Beaulieu each kept two pistols in their cabin in case such an insurrection began.[77]

English Channel

On 1 June 1799 Fayerman sailed Beaulieu to the Mediterranean Sea, but by 10 August the ship had returned to home waters, serving in the English Channel.[10][78] She recaptured the British merchant brig Harriet on 3 December, and soon afterwards began serving with the 36-gun frigate HMS Amethyst. Together they recaptured the British merchant ships Cato, on 6 December; Dauphin, on 14 December; and Cabrus and Nymphe, on 15 December.[10][79][80] Continuing their spree of recaptures, the two frigates took the British merchant brig Jenny on 18 December.[80] Some time before 24 December Beaulieu also recaptured the American merchant ship Nonpareil.[81]

Beaulieu was sailing in company with the 18-gun

Chevrette action

By July Beaulieu was serving on the blockade of

Chevrette sailed a mile closer to Brest, taking advantage of the protection of more gun batteries on shore, and brought on board a group of soldiers that increased her complement to 339 men.

The French resisted the boarding in hand-to-hand fighting, by both attacking the British as they came aboard and by attempting in turn to board their boats.[94] Despite this, members of the British force succeeded in both cutting Chevrette's anchor cable and in setting her sails. After Maxwell's force had been on board Chevrette for three minutes, the ship began to drift out of the bay. A quartermaster from Beaulieu took control of the helm, and the remaining French defenders chose to either jump overboard or run below into the ship.[95] Those defenders hiding below deck began to fire up at the British with muskets, but they were forced to surrender upon the threat of them all being killed.[94][96] Chevrette resisted the fire of the French batteries on the coast and successfully left the bay. Here Losack joined the ship and took command. In the battle the British had lost eleven men killed, with a further fifty-seven wounded and one drowned when one of Beaulieu's boats was sunk by Chevrette.[95][10][91] Ninety-two Frenchmen were killed with sixty-two wounded.[97][98] Chevrette was taken to Plymouth, arriving on 26 July.[99]

The historian

Later service

Beaulieu continued to serve in the Channel until the end of the French Revolutionary War.

Prizes

| Date | Ship | Nationality | Type | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 December 1793 | America | Merchant vessel | Captured | [20] | |

| 2 December 1794 | Not recorded | 10-gun privateer sloop | Captured | [31] | |

| 14 April 1795 | Spartiate | Schooner | Captured | [10] | |

| Unknown date 1795 | Not recorded | 18-gun store ship | Destroyed | [32] | |

| 11 March 1796 | Marsouin | 26-gun ship | Captured | [10] | |

| 8 May 1797 | Leyden and Fourcoing | Merchant hoy | Captured | [40] | |

| 3 December 1799 | Harriet | Merchant brig | Recaptured | [80] | |

| 6 December 1799 | Cato | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [79] | |

| 14 December 1799 | Dauphin | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [79] | |

| 15 December 1799 | Cabrus | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [79] | |

| 15 December 1799 | Nymphe | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [79] | |

| 18 December 1799 | Jenny | Merchant brig | Recaptured | [80] | |

| Before 24 December 1799 | Nonpareil | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [81] | |

| 27 August 1800 | Dragon | Letter of marque sloop | Captured | [83] | |

| 26 October 1800 | Diable á Quatre | 16-gun privateer | Captured | [84] | |

| 21 July 1801 | Chevrette | 20-gun corvette | Captured | [10] | |

| January 1805 | Peggy | Merchant brig | Recaptured | [106] |

Notes

- ^ In 1800 this equated to 134 tons of iron ballast and 238 tons of shingle ballast, with 207 tons of water.[15]

- ^ Repeating frigates stationed out of the line of battle mirrored the flag signals sent out by their admirals so that messages could be more easily spread throughout the fleet.[66]

- ^ Dragon alternatively recorded as a cutter captured by Beaulieu and Sylph in September.[82]

- ^ Biographer John Marshall instead records that Ekins had been in command of Beaulieu since 1801.[104]

Citations

- ^ Winfield (2007), pp. 983–984.

- ^ "Beaulieu". Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Winfield (2007), p. 983.

- ^ a b Winfield (2007), p. 986.

- ^ "Frigate". Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. 2022. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Gardiner (1999), p. 56.

- ^ Holland (2013), p. 284.

- ^ Wareham (1999), p. 30.

- ^ a b c d Gardiner (1994), p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Winfield (2007), p. 984.

- ^ a b c Gardiner (1994), p. 28.

- ^ Beaulieu's Figurehead (Sign in museum). Buckler's Hard, Hampshire: Buckler's Hard Maritime Museum.

- ^ Kennedy (1974), p. 100.

- ^ Holland (1985), p. 83.

- ^ Gardiner (1994), p. 86.

- ^ Gardiner (1994), p. 102.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1994), p. 100.

- ^ Henry (2004), p. 17.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1999), p. 58.

- ^ a b c "No. 13972". The London Gazette. 17 January 1797. p. 57.

- ^ Marley (1998), p. 358.

- ^ Brown (2017), p. 45.

- ^ Howard (2015), p. 30.

- ^ Clowes (1899), p. 247.

- ^ James (1837a), p. 216.

- ^ Brown (2017), p. 226.

- ^ "No. 15976". The London Gazette. 18 November 1806. p. 1511.

- ^ Clowes (1899), p. 248.

- ^ Clowes (1899), pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b c Marshall (1824), p. 284.

- ^ a b "No. 13751". The London Gazette. 10 February 1795. p. 147.

- ^ a b Marshall (1824), p. 285.

- ^ Nash (2008).

- ^ Marshall (1823b), p. 448.

- ^ Winfield (2008), p. 611.

- ^ "No. 13903". The London Gazette. 21 June 1796. p. 593.

- ^ James (1837a), p. 341.

- ^ Clowes (1899), p. 293.

- ^ Marshall (1823d), p. 864.

- ^ a b "No. 15268". The London Gazette. 17 June 1800. p. 698.

- ^ "No. 15252". The London Gazette. 26 April 1800. p. 409.

- ^ "To be Sold by Auction". Kentish Weekly Post. No. 1956. Canterbury. 23 October 1798. p. 1. Retrieved 15 November 2023 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Coats & MacDougall (2011), p. 171.

- ^ Coats & MacDougall (2011), p. 145.

- ^ a b c d Brown (2006), p. 69.

- ^ Brown (2006), p. 74.

- ^ Hechter, Pfaff & Underwood (2016), p. 172.

- ^ Coats & MacDougall (2011), pp. 171–172.

- ^ Brown (2006), p. 60.

- ^ Dugan (1965), p. 363.

- ^ a b c Holland (1985), p. 128.

- ^ Glasco (2001), p. 508.

- ^ Glasco (2001), pp. 508–509.

- ^ a b Holland (1985), p. 129.

- ^ Marshall (1828), p. 249.

- ^ Glasco (2001), p. 559.

- ^ Glasco (2001), p. 563.

- ^ Glasco (2001), p. 509.

- ^ Nickel (1991), p. 39.

- ^ a b Allen (1852a), p. 458.

- ^ Camperdown (1898), p. 191.

- ^ Camperdown (1898), p. 198.

- ^ a b Clowes (1899), p. 326.

- ^ Winfield (2008), p. 32.

- ^ Allen (1852a), p. 459.

- ^ Lavery (1989), p. 262.

- ^ Allen (1852a), p. 461.

- ^ a b "No. 14055". The London Gazette. 16 October 1797. p. 987.

- ^ Camperdown (1898), p. 212.

- ^ Jackson (1899), p. 304.

- ^ a b James (1837b), p. 77.

- ^ a b Marshall (1827), p. 252.

- ^ a b Willis (2013), p. 140.

- ^ James (1837b), p. 78.

- ^ Camperdown (1898), p. 214.

- ^ Laughton & Duffy (2008).

- ^ Wells (1986), p. 148.

- ^ Ward (1979), p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e "No. 15242". The London Gazette. 25 March 1800. p. 303.

- ^ a b c d "No. 15425". The London Gazette. 7 November 1801. p. 1341.

- ^ a b "No. 15221". The London Gazette. 11 January 1800. p. 38.

- ^ "No. 15335". The London Gazette. 7 February 1801. p. 164.

- ^ a b "No. 15294". The London Gazette. 16 September 1800. p. 1062.

- ^ a b "No. 15420". The London Gazette. 20 October 1801. p. 1284.

- ^ "No. 15308". The London Gazette. 4 November 1800. p. 1256.

- ^ a b O'Byrne (1849b), p. 921.

- ^ James (1837c), p. 148.

- ^ Allen (1852b), p. 50.

- ^ a b Clowes (1899), p. 539.

- ^ a b Allen (1852b), p. 51.

- ^ a b Clowes (1899), p. 540.

- ^ Morriss (2001), p. 137.

- ^ Allen (1852b), pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b James (1837c), p. 150.

- ^ a b Allen (1852b), p. 52.

- ^ a b Mostert (2007), p. 413.

- ^ Allen (1852b), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Ireland (2000), p. 164.

- ^ Mostert (2007), p. 414.

- ^ a b Allen (1852b), p. 53.

- ^ Cornwallis-West (1927), p. 361.

- ^ James (1837c), p. 152.

- ^ Marshall (1823c), p. 753.

- ^ Marshall (1823a), p. 766.

- ^ a b O'Byrne (1849a), p. 330.

- ^ a b "No. 15794". The London Gazette. 2 April 1805. p. 436.

- ^ Gardiner (2000), p. 188.

- ^ Tracy (2006), p. 134.

References

- Allen, Joseph (1852a). Battles of the British Navy. Vol. 1. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 557527139.

- Allen, Joseph (1852b). Battles of the British Navy. Vol. 2. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 557527139.

- Brown, Anthony G. (2006). "The Nore Mutiny – Sedition or Ships' Biscuits? A Reappraisal". The Mariner's Mirror. 92 (1): 60–74. .

- Brown, Steve (2017). By Fire and Bayonet: Grey's West Indies Campaign of 1794. Warwick: Helion. ISBN 978-1-915070-90-6.

- OCLC 3472413.

- OCLC 61913892.

- Coats, Ann Veronica; MacDougall, Philip (2011). The Naval Mutinies of 1797: Unity and Perseverance. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-669-8.

- OCLC 3195264.

- OCLC 711551.

- Gardiner, Robert (1994). The Heavy Frigate: Eighteen-Pounder Frigates. Vol. 1. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-627-2.

- Gardiner, Robert (1999). Warships of the Napoleonic Era. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-1171.

- Gardiner, Robert (2000). Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-135-X.

- Glasco, Jeffrey Duane (2001). "We Are A Neglected Set", Masculinity, Mutiny, and Revolution in the Royal Navy of 1797 (PhD). Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Arizona. OCLC 248530588.

- Hechter, Michael; Pfaff, Steve; Underwood, Patrick (February 2016). "Grievances and the Genesis of Rebellion: Mutiny in the Royal Navy, 1740 to 1820". American Sociological Review. 81 (1): 165–189. .

- Henry, Chris (2004). Napoleonic Naval Armaments 1792-1815. Botley, Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-635-5.

- Holland, A. J. Holland (1985). Buckler's Hard: A Rural Shipbuilding Centre. Emsworth, Hampshire: Kenneth Mason. ISBN 0-85937-328-2.

- Holland, A. J. (2013). "The Beaulieu River: Its Rise and Fall as a Commercial Waterway". The Mariner's Mirror. 49 (4): 275–287. .

- Howard, Martin R. (2015). Death Before Glory! The British Soldier in the West Indies in the French Revolutionary & Napoleonic Wars. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78159-341-7.

- ISBN 0-00-762906-0.

- OCLC 669068756.

- OCLC 963773425.

- OCLC 963773425.

- OCLC 963773425.

- Kennedy, Don H. (1974). Ship Names: Origins and Usages during 45 Centuries. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-0531-1.

- Laughton, J. K.; Duffy, Michael (2008). "Strachan, Sir Richard John, fourth baronet". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ISBN 978-0-85177-521-0.

- Marley, David F. (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. Oxford: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-87436-837-5.

- Marshall, John (1823a). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 764–767.

- Marshall, John (1823b). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 446–449.

- Marshall, John (1823c). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 753–754.

- Marshall, John (1823d). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 86–93, 864.

- Marshall, John (1824). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 2, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 283–289, 422–423.

- Marshall, John (1827). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 251–252.

- Marshall, John (1828). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 237–266.

- Morriss, Roger (2001). "The Channel and Ireland". In Robert Gardiner (ed.). Nelson against Napoleon: From the Nile to Copenhagen, 1798–1801. London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-3613.

- ISBN 978-0-224-06922-9.

- Nash, M. D. (2008). "Riou, Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Nickel, Helmut (1991). "Arms & Armors: From the Permanent Collection". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 49 (1): 1–63. JSTOR 3269006.

- A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray. pp. 329–330.

- A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray. p. 921.

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's Who in Nelson's Navy: 200 Naval Heroes. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-244-3.

- Ward, S. G. P. (1979). "The Letters of Lieutenant Edmund Goodbehere, 18th Madras N.I., 1803–1809". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 57 (229): 3–19. JSTOR 44229429.

- Wareham, Thomas Nigel Ralph (1999). The Frigate Captains of the Royal Navy, 1793–1815 (PhD). Exeter: University of Exeter. OCLC 499135092.

- Wells, Roger (1986). Insurrection: The British Experience 1795–1803. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-303-2.

- ISBN 9780857895707.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-700-6.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-78346-926-0.

External links

Media related to HMS Beaulieu (ship, 1791) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to HMS Beaulieu (ship, 1791) at Wikimedia Commons