Lake Tanganyika

| Lake Tanganyika | |

|---|---|

| Max. length | 673 km (418 mi) |

| Max. width | 72 km (45 mi) |

| Surface area | 32,900 km2 (12,700 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 570 m (1,870 ft) |

| Max. depth | 1,470 m (4,820 ft) |

| Water volume | 18,750 km3 (4,500 cu mi) |

| Residence time | 5500 years[1] |

| Shore length1 | 1,828 km (1,136 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 773 m (2,536 ft)[2] |

| Settlements | Kigoma, Tanzania Kalemie, DRC Bujumbura, Burundi Mpulungu, Zambia |

| References | [2] |

| Official name | Tanganyika |

| Designated | 2 February 2007 |

| Reference no. | 1671[3] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Lake Tanganyika (/ˌtæŋɡənˈjiːkə, -ɡæn-/;[4] Kirundi : Ikiyaga ca Tanganyika) is an African Great Lake.[5] It is the second-oldest freshwater lake in the world, the second-largest by volume, and the second deepest, in all cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia.[6][7] It is the world's longest freshwater lake.[6] The lake is shared among four countries—Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Burundi, and Zambia—with Tanzania (46%) and DRC (40%) possessing the majority of the lake. It drains into the Congo River system and ultimately into the Atlantic Ocean.[citation needed]

Geography

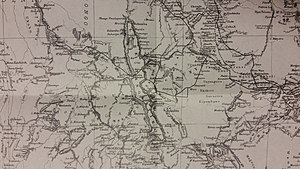

Lake Tanganyika is situated within the Albertine Rift, the western branch of the East African Rift, and is confined by the mountainous walls of the valley. It is the largest rift lake in Africa and the second-largest lake by volume in the world. It is the deepest lake in Africa and holds the greatest volume of fresh water on the continent, accounting for 16% of the world's available fresh water. It extends for 676 km (420 mi) in a general north–south direction and averages 50 km (31 mi) in width. The lake covers 32,900 km2 (12,700 sq mi), with a shoreline of 1,828 km (1,136 mi), a mean depth of 570 m (1,870 ft) and a maximum depth of 1,470 m (4,820 ft) (in the northern basin). It holds an estimated 18,750 km3 (4,500 cu mi).[8]

The catchment area of the lake is 231,000 km2 (89,000 sq mi). Two main rivers flow into the lake, as well as numerous smaller rivers and streams (whose lengths are limited by the steep mountains around the lake). The one major outflow is the Lukuga River, which empties into the Congo River drainage. Precipitation and evaporation play a greater role than the rivers. At least 90% of the water influx is from rain falling on the lake's surface and at least 90% of the water loss is from direct evaporation.[9]

The major river flowing into the lake is the Ruzizi River, formed about 10,000 years ago, which enters the north of the lake from Lake Kivu.[10] The Malagarasi River, which is Tanzania's second largest river, enters the east side of Lake Tanganyika.[10] The Malagarasi is older than Lake Tanganyika, and before the lake was formed, it probably was a headwater of the Lualaba River, the main Congo River headstream.[9]

The lake has a complex history of changing flow patterns, due to its high altitude, great depth, slow rate of refill, and mountainous location in a turbulently volcanic area that has undergone climate changes. Apparently, it has rarely in the past had an outflow to the sea. It has been described as "practically

The lake may also have at times had different inflows and outflows; inward flows from a higher Lake Rukwa, access to Lake Malawi and an exit route to the Nile have all been proposed to have existed at some point in the lake's history.[11]

Lake Tanganyika is an ancient lake, one of only twenty more than a million years old. Its three basins, which in periods with much lower water levels were separate lakes, are of different ages. The central began to form 9–12 million years ago (Mya), the northern 7–8 Mya and the southern 2–4 Mya.[12]

Water characteristics

The lake's water is

Surface temperatures generally range from about 24 °C (75 °F) in the southern part of the lake in early August to 28–29 °C (82–84 °F) in the late rainy season in March—April.

The lake is

Biology

Reptiles

Lake Tanganyika and associated wetlands are home to

Cichlid fish

The lake holds at least 250 species of

Although Tanganyika has far fewer cichlid species than Lakes

Most Tanganyika cichlids live along the shoreline down to a depth of 100 m (330 ft), but some deep-water species regularly descend to 200 m (660 ft).

Many cichlids from Lake Tanganyika, such as species from the genera Altolamprologus, Cyprichromis, Eretmodus, Julidochromis, Lamprologus, Neolamprologus, Tropheus and Xenotilapia, are popular aquarium fish due to their bright colors and patterns, and interesting behaviors.[40] Recreating a Lake Tanganyika biotope to host those cichlids in a habitat similar to their natural environment is also popular in the aquarium hobby.[40][44]

- Cichlid tribes in Lake Tanganyika (E = tribe endemic or near-endemic)

-

Benthochromini (E): Benthochromis horii was scientifically described in 2008, but has often been misidentifed as B. tricoti[47]

-

-

Cyprichromini (E): Cyprichromis microlepidotus and other members of this tribe are open-water planktivores[49][50]

-

sexually dimorphic, males being more colorful with longer fins and nose[51]

-

Haplochromini: Astatotilapia burtoni is one of the few Tanganyika species,[53] unlike other African Great Lakes where most belong to this tribe[54]

-

Lamprologini (E): Julidochromis marlieri is popular in the aquarium trade where members of the genus are known as "Julies"[55]

-

Limnochromini (E): Gnathochromis permaxillaris is a zooplanktivore with an unusual protractile mouth[56]

-

scale-eating species[57]

-

Tilapiini: Oreochromis tanganicae is one of the most common coastal species found in local fish markets[58]

Other fish

Lake Tanganyika is home to more than 80 species of non-cichlid fish and about 60% of these are endemic.[19][27][63][64]

The open waters of the pelagic zone are dominated by four non-cichlid species: Two species of "Tanganyika sardine" (

Among the more unusual fish in the lake are the endemic,

Among the non-endemic fish, some are widespread African species but several are only shared with the Malagarasi and Congo River basins, such as the

Molluscs and crustaceans

A total of 83

Crustaceans are also highly diverse in Tanganyika with more than 200 species, of which more than half are endemic.

Among Rift Valley lakes, Lake Tanganyika far surpasses all others in terms of crustacean and freshwater snail richness (both in total number of species and number of endemics).[82] For example, the only other Rift Valley lake with endemic freshwater crabs are Lake Kivu and Lake Victoria with two species each.[83][84]

Other invertebrates

The diversity of other invertebrate groups in Lake Tanganyika is often not well-known, but there are at least 20 described species of leeches (12 endemics),[85] 9 sponges (7 endemic), 6 bryozoa (2 endemic), 11 flatworms (7 endemic), 20 nematodes (7 endemic), 28 annelids (17 endemic)[27] and the small hydrozoan jellyfish Limnocnida tanganyicae.[86]

Fishing

Lake Tanganyika supports a major fishery, which, depending on source, provides 25–40%[87] or c. 60% of the animal protein in the diet of the people living in the region.[16][88]

Lake Tanganyika fish can be found exported throughout East Africa. Major commercial fishing began in the mid-1950s and has, together with global warming, had a heavy impact on the fish populations, causing significant declines.[16][88][15] In 2016, it was estimated that the total catch was up to 200,000 tonnes.[16]

History

It is thought that early

There are many methods in which the native people of the area were fishing. Most of them included using a lantern as a lure for fish that are attracted to light. There were three basic forms. One called Lusenga which is a wide net used by one person from a canoe. The second one is using a lift net. This was done by dropping a net deep below the boat using two parallel canoes and then simultaneously pulling it up. The third is called Chiromila which consisted of three canoes. One canoe was stationary with a lantern while another canoe holds one end of the net and the other circles the stationary one to meet up with the net.[90]

The first known Westerners to find the lake were the British explorers

The lake was the scene of

References

- ^ Yohannes, Okbazghi (2008). Water resources and inter-riparian relations in the Nile basin. SUNY Press. p. 127.

- ^ a b "LAKE TANGANYIKA". www.ilec.or.jp. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ "Tanganyika". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- )

- ^ a b c "Lake Tanganyika". www.zambiatourism.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ Lewis, R. (16 May 2010). "Brown Geologists Show Unprecedented Warming in Lake Tanganyika". Brown University. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Datbase Summary: Lake Tanganyika". ilec.or.jp. Japan: International Lake Environment Committee Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 November 1999. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d Kullander, S.O.; Roberts, T.R. (2011). "Out of Lake Tanganyika: endemic lake fishes inhabit rapids of the Lukuga River". Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters. 22 (4): 355–76.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- ^ Lévêqu, Christian (1997). Biodiversity Dynamics and Conservation: The Freshwater Fish of Tropical Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 110.

- .

- ^ PMID 16151083.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 1637315.

- ^ a b c d Jensen, M.R. (8 August 2016). "Lake Tanganyika Fisheries Declining From Global Warming". University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Lowe-McConnell, R.H. (2003). "Recent research in the African Great Lakes: Fisheries, biodiversity and cichlid evolution". Freshwater Forum. 20 (1): 4–64.

- ISBN 978-3-642-15178-1.

- ^ a b c d e Wright, J.J.; and L.M. Page (2006). Taxonomic revision of Lake Tanganyikan Synodontis (Siluriformes: Mochokidae). Florida Mus. Nat. Hist. Bull. 46(4): 99–154.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-28064-8.

- )

- ^ ISBN 0-12-656470-1.

- ^ O'Shea, Mark; Mcintyre, P.B. (2005). "Boulengerina annulata stormsi (Storm's water cobra). Attempted predation". Herpetological Review. 36 (2): 189. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ a b c d e Kelly West (28 February 2001). "Results and Experiences of the UNDP/GEF Conservation Initiative (RAF/92/G32) in Burundi, D.R. Congo, Tanzania, and Zambia". IW:LEARN | Documents. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Craig Mortiff (24 December 2009). "Lake Tanganyika and its Diverse Cichlids". Cichlid Fish Forum. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- PMID 22675655.

- .

- ^ PMID 25433288.

- S2CID 12925712.

- PMID 25983053.

- S2CID 37599331.

- S2CID 36086310.

- ^ PMID 22675652.

- ISBN 978-1564651464.

- ^ ISBN 978-0792360179

- S2CID 155438716.

- ^ ISBN 978-0812013504.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2017). "Neolamprologus multifasciatus" in FishBase. March 2017 version.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2017). "Neolamprologus similis" in FishBase. March 2017 version.

- ^ a b "The 10 biggest cichlids". Practical Fishkeeping. 13 June 2016. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "tanganyika biotope aquarium". Aquariums Life. 10 February 2010. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- PMID 25928886.

- ^ PMID 25433288.

- .

- S2CID 83854866.

- . Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ ISBN 0-7641-0615-5

- ^ "Ophthalmotilapia nasuta". Seriously Fish. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2017). "Eretmodus cyanostictus" in FishBase. April 2017 version.

- ^ a b c d "Species in the Tanganyika". www.fishbase.se (table). Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- S2CID 54011001.

- ^ "Julidochromis marlieri (Marlier's Julie)". Seriously Fish. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- . Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- PMID 20102595.

- . Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ISBN 0-12-013926-X

- PMID 16543167.

- ^ Robert Toman (2017). "Tropheus Genus Evolution". Cichlid World. Archived from the original on 19 September 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). Species of Lamprichthys in FishBase. March 2017 version.

- ^ .

- .

- ^ "Synodontis grandiops • Mochokidae". www.planetcatfish.com. 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Synodontis lucipinnis • Mochokidae". www.planetcatfish.com. 2023. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2023."Synodontis petricola • Mochokidae". www.planetcatfish.com. 2023. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- PMID 28744868.

- ^ PMID 20565906.

- ^ )

- ^ ISBN 0-7484-0026-5

- PMID 28568935.

- PMID 17254340.

- PMID 16647274.

- S2CID 44127332.

- . Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- S2CID 207150861.

- PMID 25902063.

- S2CID 14831643.

- from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- S2CID 22945163.

- . Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ISBN 1-4020-3745-7

- ^ Cumberlidge, N.; and Meyer, K. S. (2011). A revision of the freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa. Archived 25 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Journal Articles. Paper 30.

- hdl:10141/622400.

- ISBN 1-4020-3745-7

- ^ Salonen; Högmander; Langenberg; Mölsä; Sarvala; Tarvainen; and Tiirola (2012). Limnocnida tanganyicae medusae (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa): a semiautonomous microcosm in the food web of Lake Tanganyika. Hydrobiologia 690(1): 97–112.

- ^ "Global warming is killing off tropical lake fish – Study of Lake Tanganyika". www.mongabay.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ a b McGrath, M. (8 August 2016). "Decline of fishing in Lake Tanganyika 'due to warming'". BBC. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ East African Ecosystems and Their Conservation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Lake Tanganyika and Its Life. Oxford Press. 1991.

- ISBN 978-0-554-26021-1.

- JSTOR 428776.

- ^ a b c Giles Foden: Mimi and Toutou Go Forth — The Bizarre Battle for Lake Tanganyika, Penguin, 2004.

External links

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Tanganyika". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- "Tanganyika". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Tanganyika". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

![Bathybatini (E): Bathybates ferox is benthic and piscivorous, but the genus also includes pelagic species.[36] The tribe is sometimes split in three, others being Hemibatini and Trematocarini[45][46]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Bathybates_ferox.jpg/389px-Bathybates_ferox.jpg)

![Benthochromini (E): Benthochromis horii was scientifically described in 2008, but has often been misidentifed as B. tricoti[47]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/af/Benthochromis_tricoti.jpg/247px-Benthochromis_tricoti.jpg)

![Boulengerochromini (E): Boulengerochromis microlepis is one of the world's largest cichlids[43] and only member of its tribe[46]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/68/DKoehl_Boulengerochromis_microlepis.jpg/285px-DKoehl_Boulengerochromis_microlepis.jpg)

![Cyphotilapiini (E): Cyphotilapia frontosa, one of only two similar species in the tribe[48]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/Cyphotilapia_frontosa2.jpg/208px-Cyphotilapia_frontosa2.jpg)

![Cyprichromini (E): Cyprichromis microlepidotus and other members of this tribe are open-water planktivores[49][50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/Kleinschuppiger_Kaerpflingsbuntbarsch_Cyprichromis_microlepidotus_Tierpark_Hellabrunn-1.jpg/229px-Kleinschuppiger_Kaerpflingsbuntbarsch_Cyprichromis_microlepidotus_Tierpark_Hellabrunn-1.jpg)

![Ectodini (E): Ophthalmotilapia nasuta (male) is sexually dimorphic, males being more colorful with longer fins and nose[51]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a4/Ophthalmotilapia_nasuta_Kipili.jpg/264px-Ophthalmotilapia_nasuta_Kipili.jpg)

![Eretmodini (E): Eretmodus cyanostictus lives near the bottom in the turbulent, coastal surf zone,[52] like other members of its tribe[50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/06/Eretmodus-sp-kavala1.jpg/232px-Eretmodus-sp-kavala1.jpg)

![Haplochromini: Astatotilapia burtoni is one of the few Tanganyika species,[53] unlike other African Great Lakes where most belong to this tribe[54]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Astatotilapia_burtoni.png/191px-Astatotilapia_burtoni.png)

![Lamprologini (E): Julidochromis marlieri is popular in the aquarium trade where members of the genus are known as "Julies"[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Schachbrett-Schlankcichlide.jpg/225px-Schachbrett-Schlankcichlide.jpg)

![Limnochromini (E): Gnathochromis permaxillaris is a zooplanktivore with an unusual protractile mouth[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/85/Gnathochromis_premaxillaris.jpg/200px-Gnathochromis_premaxillaris.jpg)

![Perissodini (E): Perissodus microlepis, a specialized scale-eating species[57]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Perissodus_microlepis_juvenile_in_aquarium.jpg/203px-Perissodus_microlepis_juvenile_in_aquarium.jpg)

![Tilapiini: Oreochromis tanganicae is one of the most common coastal species found in local fish markets[58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7e/Oreochromis_tanganicae_%28G%C3%BCnther%29.jpg/243px-Oreochromis_tanganicae_%28G%C3%BCnther%29.jpg)

![Tropheini (E): Tropheus moorii ("red" Chimba morph) is highly variable and the taxonomy of some of the morphs is questionable[59][60][61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/TropheusspRed200.jpg/242px-TropheusspRed200.jpg)