Metals of antiquity

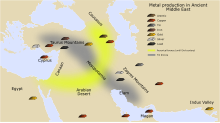

The metals of antiquity are the seven metals which humans had identified and found use for in prehistoric times in Africa, Europe and throughout Asia:[1] gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, iron, and mercury. These seven are the metals from which the classical world was forged.

History

Copper was probably the first metal mined and crafted by humans.

It is believed that lead smelting began at least 9,000 years ago, and the oldest known artifact of lead is a statuette found at the temple of Osiris on the site of Abydos dated around 3800 BC.[12] It was recognised as an element by Guyton de Morveau, Lavoisier, Berthollet, and Fourcroy in 1787.[6]

The earliest gold artifacts were discovered at the site of

There is evidence that iron was known from before 5000 BC.[15] The oldest known iron objects used by humans are some beads of meteoric iron, made in Egypt in about 4000 BC. The discovery of smelting around 3000 BC led to the start of the Iron Age around 1200 BC[16] and the prominent use of iron for tools and weapons.[17] It was recognised as an element by Guyton de Morveau, Lavoisier, Berthollet, and Fourcroy in 1787.[6]

Tin was first smelted in combination with copper around 3500 BC to produce bronze (and thus giving place to the Bronze Age (except in some places which did not experience a significant Bronze Age, passing directly from the Neolithic Stone Age to the Iron Age)).[18] Kestel, in southern Turkey, is the site of an ancient Cassiterite mine that was used from 3250 to 1800 BC.[19] The oldest artifacts date from around 2000 BC.[20] It was recognised as an element by Guyton de Morveau, Lavoisier, Berthollet, and Fourcroy in 1787.[6]

Characteristics

Melting point

The metals of antiquity generally have low melting points, with iron being the exception.

- Mercury melts at −38.829 °C (−37.89 °F)[21] (being liquid at room temperature).

- Tin melts at 231 °C (449 °F)[21]

- Lead melts at 327 °C (621 °F)[21]

- Silver at 961 °C (1763 °F)[21]

- Gold at 1064 °C (1947 °F)[21]

- Copper at 1084 °C (1984 °F)[21]

- Iron is the outlier at 1538 °C (2800 °F),[21] making it far more difficult to melt in antiquity. Cultures developed ironworking proficiency at different rates; however, evidence from the Near East suggests that smelting was possible but impractical circa 1500 BC, and relatively commonplace across most of Eurasia by 500 BC.[22] However, until this period, generally known as the Iron Age, ironwork would have been impossible.

The other metals discovered before the Scientific Revolution largely fit the pattern, except for high-melting platinum:

- Bismuth melts at 272 °C (521 °F)[21]

- Zinc melts at 420 °C (787 °F),[21] but importantly boils at 907 °C (1665 °F), a temperature below the melting point of silver. Consequently, at the temperatures needed to reduce zinc oxide to the metal, the metal is already gaseous.[23][24]

- Arsenic sublimes at 615 °C (1137 °F), passing directly from the solid state to the gaseous state.[21]

- Antimony melts at 631 °C (1167 °F)[21]

- Platinum melts at 1768 °C (3215 °F), even higher than iron.[21] Native South Americans worked with it instead by sintering: they combined gold and platinum powders, until the alloy became soft enough to shape with tools.[25][26]

Extraction

While all the metals of antiquity but tin and lead occur natively, only gold and silver are commonly found as the native metal.

- Gold and silver occur frequently in their native form

- Mercury compounds are reduced to elemental mercury simply by low-temperature heating (500 °C).

- Tin and iron occur as oxides and can be reduced with carbon monoxide (produced by, for example, burning charcoal) at 900 °C.

- Copper and lead compounds can be roasted to produce the oxides, which are then reduced with carbon monoxide at 900 °C.

- Meteoric iron is often found as the native metal and it was the earliest source for iron objects known to humanity

Symbolism

The practice of alchemy in the Western world, based on a Hellenistic and Babylonian approach to planetary astronomy, often ascribed a symbolic association between the seven then-known celestial bodies and the metals known to the Greeks and Babylonians during antiquity. Additionally, some alchemists and astrologers believed there was an association, sometimes called a rulership, between days of the week, the alchemical metals, and the planets that were said to hold "dominion" over them.[27][28] There was some early variation, but the most common associations since antiquity are the following:

| Metal | Body | Symbol | Day of week |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold | Sun | ☉︎ | Sunday |

| Silver | Moon | ☾ | Monday |

| Iron | Mars | ♂ | Tuesday |

| Mercury | Mercury | ☿ | Wednesday |

| Tin | Jupiter | ♃ | Thursday |

| Copper | Venus | ♀ | Friday |

| Lead | Saturn | ♄ | Saturday |

See also

- Timeline of chemical element discoveries

- Ashtadhatu, the eight metals of Hindu alchemy (these seven plus zinc)

- History of metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent

- History of metallurgy in China

- Metallurgy in pre-Columbian America

- Copper metallurgy in Africa

- Iron metallurgy in Africa

References

This article has an unclear citation style. (April 2018) |

- ^ Smith, Cyril Stanley; Forbes, R.J. (1957). "2: Metallurgy and Assaying". In Singer; Holmyard; Hall; Williams (eds.). A History Of Technology. Oxford University Press. p. 29.

- ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- ISBN 9780198146872. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ISBN 9780486262987. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Biswas, Arun Kumar (1993). "The Primacy of India in Ancient Brass and Zinc Metallurgy" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 28 (4): 309–330. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ .

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1960). Discovery of the Elements (6th ed.). Journal of Chemical Education. p. 153.

- ^ "Copper History". Rameria.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-17. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ "CSA – Discovery Guides, A Brief History of Copper". Archived from the original on 2015-02-03. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ "Serbian site may have hosted first copper makers". UCL.ac.uk. UCL Institute of Archaeology. 23 September 2010. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Bruce Bower (July 17, 2010). "Serbian site may have hosted first copper makers". ScienceNews. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ "The History of Lead – Part 3". Lead.org.au. Archived from the original on 2004-10-18. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- S2CID 143173212.

- ^ "47 Silver".

- ^ "26 Iron". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- LCCN 68-15217.

- ^ "Notes on the Significance of the First Persian Empire in World History". Courses.wcupa.edu. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ "50 Tin". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- JSTOR 1357777

- ^ "History of Metals". Neon.mems.cmu.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Winter, Mark. "The periodic table of the elements by WebElements". www.webelements.com.

- .

- . Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- .

- S2CID 4100269.

- ISSN 0003-813X.

- ISBN 978-0-09-945787-9.

- ^ Kollerstrom, Nick. "The Metal-Planet Relationship: A Study of Celestial Influence". homepages.ihug.com.au. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "History of Metals". Archived from the original on 2007-01-08.

- Nick Kollerstrom. "The Metal-Planet Affinities - The Sevenfold Pattern". Retrieved 2011-02-17.

Further reading

- http://www.webelements.com/ cited from these sources:

- A.M. James and M.P. Lord in Macmillan's Chemical and Physical Data, Macmillan, London, UK, 1992.

- G.W.C. Kaye and T.H. Laby in Tables of physical and chemical constants, Longman, London, UK, 15th edition, 1993.