Name of Bosnia

The name of

From the name of Bosnia, various local terms (

Etymology

The name of the polity of Bosnia as per traditional view in linguistics originated as a

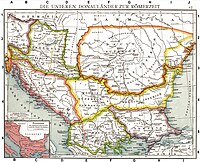

The river may have been mentioned for the first time in the 1st century AD by Roman historian

In the Slavic languages, -ak is a common suffix appended to words to create a masculine noun, for instance also found in the ethnonym of Poles (Polak) and Slovaks (Slovák). As such, "Bosniak" is etymologically equivalent to its non-ethnic counterpart "Bosnian" (which entered English around the same time via the Middle French, Bosnien): a native of Bosnia.[15]

Medieval terms for Bosnia and its population

The first mention of a Bosnia is from De Administrando Imperio (DAI; c. 960), which mentions it as χοριον Βοσωνα (horion Bosona, a "small country Bos(o)na").[16]

In following centuries, the name was used as a designation for a medieval polity, called the Banate of Bosnia and transformed by 1377 into the Kingdom of Bosnia. After the Ottoman conquest in 1463, the name was adopted and used as a designation for the Sanjak of Bosnia

From the name of Bosnia and depending on era, various local

Terminology from the Ottoman period

After the

During this period, demonym

The 17th-century Ottoman traveler and writer

During the 19th century, many prominent Catholics were staunch proponent of

"Bosniaks" as a demonym in Early modern Western use

According to the Bosniak entry in the Oxford English Dictionary, the first preserved use of "Bosniak" in English was by British diplomat and historian Paul Rycaut in 1680 as Bosnack, cognate with post-classical Latin Bosniacus (1682 or earlier), French Bosniaque (1695 or earlier) or German Bosniak (1737 or earlier).[25] The modern spelling is contained in the 1836 Penny Cyclopaedia V. 231/1: "The inhabitants of Bosnia are composed of Bosniaks, a race of Sclavonian origin".[26]

Bosniak ethnonym

During Yugoslavia, the term "Muslims" (

References

- ^ Moravcsik 1967, p. 160-161.

- ^ Indira Šabić (2014). Onomastička analiza bosanskohercegovačkih srednjovjekovnih administrativnih tekstova i stećaka (PDF). Osijek: Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera. pp. 165–167.

- ISBN 9789958031106.

- ^ Salmedin Mesihović (2010). AEVVM DOLABELLAE – DOLABELINO DOBA. Vol. XXXIX. Sarajevo: Centar za balkanološka ispitivanja, Akademija nauka i umjetnosti. p. 10.

- ^ ISBN 9781107455535.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ISBN 9781109124637.

- ^ a b Indira Šabić (2014). Onomastička analiza bosanskohercegovačkih srednjovjekovnih administrativnih tekstova i stećaka (PDF). Osijek: Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera. p. 165.

- ^ "Filozofski fakultet Osijek" (PDF). 2017-01-14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-14. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ Rizvić, Muhsin (1996). Bosna i Bošnjaci (in Bosnian). Sarajevo. p. 6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lelewel, Joachim. Géographie du moyen âge (in French). p. 43.

- ^ Zeuss, Johan Kaspar (1837). Die Deutschen und die Nachbarstämme (in German). p. 615.

- ^ Vego, Marko. Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države (in Bosnian). Svjetlost. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Hadžijahić, Muhamed (2004). Povijest Bosne u IX i X stoljeću (in Bosnian). pp. 113, 164–165.

- ^ Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka (in Bosnian). Sarajevo: Preporod. pp. 24–25.

- ^ "Bosnian". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- ^ Kaimakamova & Salamon 2007, p. 244.

- ISBN 9781850657675.

- ^ Nakaš, Župarić, Lalić, Dautović, Kurtović, (2018), Codex diplomaticus regni bosnae - povelje i pisma stare bosanske države, pp. 70, 73, 75, 79, 93, 96, 99, 107, 112, 381, Mladinska knjiga Sarajevo

- ^ Hadžijahić 1974, p. 7.

- ISBN 978-1-78076-111-4.

- ^ Evlija Čelebi, Putopis: odlomci o jugoslavenskim zemljama, (Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1967), p. 120

- ^ Donia & Fine 1994, p. 73.

- ISSN 0350-6398.

- ^ Marko Atilla Hoare, (2007), The history of Bosnia: from the Middle ages to the Present day, p.60

- ^ "Bosniak". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- ^ Charles Knight (1836). The Penny Cyclopaedia. Vol. V. London: The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. p. 231.

- ^ Motyl 2001, pp. 57.

- ^ "VKBI: Navršava se 27 godina od vraćanja imena Bošnjaci i bosanski jezik | Sarajevo.ba". www.sarajevo.ba (in Bosnian). 27 Sep 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

Sources

- Donia, Robert J.; Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994). Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-212-0.

- Hadžijahić, Muhamed (1990) [1974]. Od tradicije do identiteta: geneza nacionalnog pitanja bosanskih Muslimana. Islamska zajednica.

- Kaimakamova, Miliana; Salamon, Maciej (2007). Byzantium, new peoples, new powers: the Byzantino-Slav contact zone, from the ninth to the fifteenth century. Towarzystwo Wydawnicze "Historia Iagellonica". ISBN 978-83-88737-83-1.

- ISBN 9780884020219.

- ISBN 0-12-227230-7.