Naram-Sin of Akkad

| Naram-Sin 𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪 | |

|---|---|

| |

Portrait of Naram-Sin | |

| King of the Akkadian Empire | |

| Reign | c. 2254 – 2218 BC |

| Predecessor | Manishtushu |

| Successor | Sharkalisharri |

| Issue | Shar-Kali-Sharri |

| Dynasty | Dynasty of Akkad |

| Father | Manishtushu |

Naram-Sin, also transcribed Narām-Sîn or Naram-Suen (

Biography

Naram-Sin was a son of Manishtushu. He was thus a nephew of King Rimush and grandson of Sargon and Tashlultum. Naram-Sin's aunt was the High Priestess En-hedu-ana. Most recensions of the Sumerian King List show him following Manishitshu but The Ur III version of the king list inverts the order of Rimush and Manishtushu.[4][5] To be fully correct, rather than Naram-Sin or Naram-Suen "in Old Akkadian, the name in question should rather be reconstructed as Naram-Suyin (more precisely, /narām-tsuyin/) or Naram-Suʾin (/narām-tsuʾin/)".[6]

Naram-Sin defeated Manium of Magan, and various northern hill tribes in the

During his reign Namar-Sin increased direct royal control of its city-states. He maintained control over the various city-states by the simple expedient of appointing some of his many sons as key provincial governors, and his daughters as high priestesses. He also reformed the scribal system.[9][10]

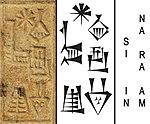

A few loyal local governors remained in place. This included Meskigal, as governor of the city-state of Adab and Karsum governor of the unlocated Niqqum. Another was Lugal-ushumgal of Lagash. Several inscriptions of Lugal-ushumgal, who went on to serve the successor of Naram-Sin, Shar-Kali-Sharri, are known, particularly seal impressions, which refer to him as governor of Lagash and at the time a vassal (𒀵, arad, "servant" or "slave") of Naram-Sin.[11]

Naram-Sin, the mighty God of Agade,

, is thy servant.— Seal of Lugal-ushumgal as vassal of Naram-sin.

The Great Revolt

The pivotal event of Naram-Sin's reign was a widespread revolt against the Akkadian Empire. The empire created by his grandfather, Sargon, first ruler of the Akkadian Empire stretched in the west to Syria in places like Tell Brak and Tell Leilan, to the east in Elam and associated polities in that region, to southern Anatolia in the north, and to the "lower sea" in the south encompassing all the traditional Sumerian powers like Uruk, Ur, and Lagash. All of these political entities had long histories as independent powers and would periodically re-assert their interests throughout the lifetime of the Akkadian Empire.[12]

At some point in his reign a widespread uprising occurred, a large coalition of city-states led by Iphur-Kis of Kish (Sumer) and Amar-Girid of Uruk, joined by Enlil-nizu of Nippur, and including the city-states of "Kutha, TiWA, Sippar, Kazallu, Kiritab, [Api]ak and GN" as well as "Amorite [hi]ghlanders". The rebellion was joined by the city of Borsippa, among others.[13][14] We know of these events from a number of Old Babylonian copies of earlier inscriptions as well as one contemporary record from the Old Akkadian period. The Bassetki Statue, discovered in 1974, was the base of a life-sized copper statue of Naram-Sin. It reads:

"Naram-Sin, the mighty, king of Agade, when the four quarters together revolted against him, through the love which the goddess Astar showed him, he was victorious in nine battles in one in 1 year, and the kings whom they (the rebels[?]) had raised (against him), he captured. In view of the fact that he protected the foundations of his city from danger, (the citizens of his city requested from Astar in Eanna, Enlil in Nippur, Dagan in Tuttul, Ninhursag in Kes, Ea in Eridu, Sin in Ur, Samas in Sippar, (and) Nergal in Kutha, that (Naram-Sin) be (made) the god of their city, and they built within Agade a temple (dedicated) to him. As for the one who removes this inscription, may the gods Samas, Astar, Nergal, the bailiff of the king, namely all those gods (mentioned above) tear out his foundations and destroy his progeny."[15]

In the aftermath, Naram-Sin deified himself as well as posthumously deifying Sargon and Manishtushi but not his Rimush.[16][17] The echoes of the revolt were reflected in later Sumerian literary compositions such as the Great Revolt against Naram-Sin, "Naram-Sin and the Enemy Hordes" and "Gula-AN and the Seventeen Kings against Naram-Sin".[18] [19][20]

Control of Elam

Elam came under the domination of Akkad in the time of Sargon though it remained restive. The 2nd ruler of Akkad, Rimush, campaigned there afterward adding "conqueror of Elam and Parahsum" to his royal titulary. The 3rd ruler, Manishtushu, conquered the city of Anshan in Elam and also the city of Pashime, installing imperial governors in those places.[21]

Naram-Sin added "commander of all the land of Elam, as far as Parahsum," to his royal titulary. During his rule, "military governors of the country of Elam" (shakkanakkus) with typically Akkadian names are known, such as Ili-ishmani or Epirmupi.[21][22][23][24] This suggests that these governors of Elam were officials of the Akkadian Empire.[21] Naram-Sin exercised great influence over Susa during his reign, building temples and establishing inscriptions in his name, and having the Akkadian language replace Elamite in official documents.[25]

An unknown Elamite king (sometimes speculated to be

Conquest of Armanum and Ebla

The conquest of Armanum (location unknown but proposed as Tall Bazi) with its ruler Rid-Adad and Ebla (55 kilometers southwest of modern Aleppo) by Naram-Sin (Ebla was also defeated by his grandfather Sargon) is known from one of his year names "The year the king went on a campaign in Amarnum" and from an Old Babylonian copy of a statue inscription (IM 85461) found at Ur. There are also three objects, a marble lamp, a stone plaque, and a copper bowl, inscribed "Naram-Sin, the mighty, king of the four quarters, conqueror of Armanum and Ebla.".[32][33] In 2010 a new stele fragment (IM 221139) describing the campaign was found at Tulul al-Baqarat (thought to be the ancient city of Kesh.[6]

"Whereas, for all time since the creation of mankind, no king whosoever had destroyed Armanum and Ebla, the god Nergal, by means of (his) weapons opened the way for Naram-Sin, the mighty, and gave him Armanum and Ebla. Further, he gave to him the Amanus, the Cedar Mountain, and the Upper Sea. By means of the weapons of the god Dagan, who magnifies his kingship, Naram-Sin, the mighty, conquered Armanum and Ebla."

— Inscription of Naram-Sin. E 2.1.4.26[15]

Children

Among the known sons of Naram-Sin were his successor

Victory stele of Naram-Sin

Naram-Sin's

The inscription over the head of the king is in the Akkadian language and very fragmentary, but reads:

"[Nar]am-Sin, the mighty, <Lacuna> ..., Sidu[r-x] (and) the highlanders of Lullubum assembled together ... bat[tle]. For/to <Lacuna> the high[landers ...] <Lacuna> [heap]ed up [a burial mound over them], ... (and) dedicated (this object) [to the god ...] <Lacuna> [15]

"I am Shutruk-Nahhunte, son of Hallutush-Inshushinak, beloved servant of the god Inshushinak, king of Anshan and Susa, who has enlarged the kingdom, who takes care of the lands of Elam, the lord of the land of Elam. When the god Inshusinak gave me the order, I defeated Sippar. I took the stele of Naram-Sin and carried it off, bringing it to the land of Elam. For Inshushinak, my god, I set it as an offering."[46]

A similar stele fragment (ES 1027), 57 centimeters high by 42 centimeters wide by 20 deep, depicting Naram-Sin was found a few miles north-east of

Fragments of an alabaster stele representing captives being led by Akkadian soldiers is sometimes attributed to Narim-Sin (or

It is thought that the stele represents the result of the campaigns of Naram-Sin to Cilicia or Anatolia. This is suggested by the characteristics of the booty carried by the soldiers in the stele, especially the metal vessel carried by the main soldier, the design of which is unknown in Mesopotamia, but on the contrary well known in contemporary Anatolia.[48]

-

Soldier with sword, on the Nasiriyah stele of Naram-Sin

-

Naked captives, on the Nasiriyah stele of Naram-Sin

The Curse of Akkad

One Mesopotamian myth, a historiographic poem entitled "The curse of Akkad: the Ekur avenged", explains how the empire created by

Its chariot roads grew nothing but the 'wailing plant,

Moreover, on its canalboat towpaths and landings,

No human being walks because of the wild goats, vermin, snakes, and mountain scorpions,

The plains where grew the heart-soothing plants, grew nothing but the 'reed of tears,

Akkad, instead of its sweet-flowing water, there flowed bitter water,

Who said "I would dwell in that" found not a good dwelling place,

Who said "I would lie down in Akkad" found not a good sleeping place.

Excavations by Nabonidus circa 550 BC

A foundation deposit of Naram-Sin was discovered and analysed by king Nabonidus, circa 550 BC.[52] who Robert Silverberg thus characterises as the first archaeologist. Not only did he lead the first excavations which were to find the foundation deposits of the temples of Šamaš the sun god, the warrior goddess Anunitu (both located in Sippar), and the sanctuary that Naram-Sin built to the moon god, located in Harran, but he also had them restored to their former glory.[53] He was also the first to date an archaeological artefact in his attempt to date Naram-Sin's temple during his search for it. His estimate was inaccurate by about 1,500 years.[54]

In popular culture

King Naram-Sin is a character in the 2021 video game House of Ashes, with the main plot occurring in his personal temple.[55] In the game, he is the self-proclaimed "God King" of Akkad, and is engaged in a war with the Gutians after being cursed by the god Enlil; whom he angered after the sacking his temple. Naram-Sin was voiced and motion captured by Sami Karim.

In the 2021 mobile gacha game Blue Archive, Volume F, the innermost chamber of the large floating quantum supercomputer known as the "Ark of Atra-Hasis" (itself a reference to the Akkadian myth) is named "Throne of Naram-Sin".

Artifacts of Naram-Sin

-

Seals in the name of Naram-Sin

-

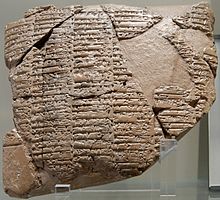

Stele of the Akkadian king Naram-Sin. The "-ra-am" and "-sin" parts of the name "Naram-Sin" appear in the broken top right corner of the inscription.Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

-

Portrait of Naram-Sin (detail)

-

The name "Naram-Sin" in cuneiform on an inscription. The star symbol "Sîn(Moon God) is specially written with the characters "EN-ZU" (𒂗𒍪).

-

Gold foil in the name of Naram-Sin.

-

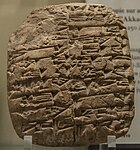

Copy of an inscription of Naram-Sin. Louvre Museum AO 5475

-

Diorite base of statue of Naram-sin

-

Fragment of a statue in the name of Naram-Sin, Louvre Museum Sb 53

-

"Naram-Sin, king of the four quarters, dedicated (this mace) to the goddess Ishtar at Nippur"

-

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, c. 2230 BC. It shows him defeating the Lullibi, a tribe in the Zagros Mountains, and their king Satuni, trampling them and spearing them. Satuni, standing right, is imploring Naram-Sin to save him.[61] Naram-Sin is also twice the size of his soldiers.

See also

- List of kings of Akkad

- List of Mesopotamian dynasties

- History of Mesopotamia

- Sumerian king list

- House of Ashes

References

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr, "The Divine Rulers of Akkade and Ur: Toward a Definition of the Deification of Kings in Babylonia", History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 107-157, 2017

- ^ Lambert, W. G., "Narām-Sîn of Ešnunna or Akkad?", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 106, no. 4, pp. 793–95, 1986

- ^ von Dassow, Eva., "Narām-Sîn of Uruk: A New King in an Old Shoebox", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 61, pp. 63–91, 2009

- ^ Steinkeller, P., "An Ur III manuscript of the Sumerian King List", in: W. Sallaberger [e.a.] (ed.), Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien. Festschrift für Claus Wilcke, OBC 14, Wiesbaden, 267–29, 2003

- ^ Thomas, Ariane, "The Akkadian Royal Image: On a Seated Statue of Manishtushu", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 105, no. 1-2, pp. 86-117, 2015

- ^ a b Nashat Alkhafaji and Gianni Marchesi, "Naram-Sin's War against Armanum and Ebla in a Newly-Discovered Inscription from Tulul al-Baqarat", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 1-20, 2020

- ^ Cohen, Mark E. “A New Naram-Sin Date Formula.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 28, no. 4, 1976, pp. 227–32

- ^ Year-Names of Naram-Sin of Agade

- ^ Foster, B.R., "The Age of Agade. Inventing empire in ancient Mesopotamia". London New York, 2016

- ^ [1]M. Molina, "The palace of Adab during the Sargonic period", D. Wicke (ed.), Der Palast im antiken und islamischen Orient, Colloquien der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 9, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2019, pp. 151-20

- ^ "CDLI-Archival View RT 165". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ Weiss, Harvey, " Excavations at Tell Leilan and the Origins of North Mesopotamian cities in the Third Millennium B.C.", Paléorient, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 39–52, 1983

- ^ Steve Tinney, A New Look at Naram-Sin and the "Great Rebellion", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 47, pp. 1-14, 1995

- ^ Wilcke, Claus, "Amar-girids Revolte gegen Narām-Suʾen", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 11-32, 1997

- ^ ISBN 0-8020-0593-4

- ^ William W. Hallo, "Royal Titles from the Mesopotamian Periphery", Anatolian Studies 30, pp. 89–19, 1980

- ^ Stepien, Marek, "Why Some Kings Become Gods: The Deification of Naram-Sin, Ruler of the World", Here & There Across the Ancient Near East: Studies in Honour of Krystyna Lyczkowska, Warszawa: Agape, pp. 233-255, 2009

- ^ [3]Westenholz, Joan Goodnick, "Heroes of Akkad", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 327–36, 1983

- ^ Westenholz, Joan Goodnick. "The Great Revolt against Naram-Sin". Legends of the Kings of Akkade: The Texts, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 221-262, 1997

- ^ Westenholz, Joan Goodnick, "Naram-Sin and the Enemy Hordes”: The “Cuthean Legend” of Naram-Sin", Legends of the Kings of Akkade: The Texts, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 263-368, 1997

- ^ ISBN 978-1-107-09469-7.

- ^ "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ISBN 978-1-000-03485-1.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ W. G. Lambert, "The Akkadianization of Susiana under the Sukkalmahs", MHEOP 1, pp. 53-7 Mesopotamie et Elam, Ghent: Mesopotamian History and Environment Occasional Publications 1, 1991

- ^ Hinz, Walther, "Elams Vertrag mit Narām-Sîn von Akkade", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 58, no. Jahresband, pp. 66-96, 1967

- ^ Pittman, Holly, "The “Jeweler’s” Seal from Susa and Art of Awan", Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen, edited by Erica Ehrenberg, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 211-236, 2002

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Scheil, V, "Textes Élamites-Anzanites", MDP XI, 1911

- ^ Cameron, G.G., "History of Early Iran", Chicago/London: University of Chicago, 1936

- ^ Westenholz, Aage, Pascal Attinger, and Markus Wäfler, "The Old Akkadian Period: History and Culture", Mesopotamien. Annäherungen 3: Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit, pp. 17-117, 1999

- ISBN 0-226-62309-2

- ^ [5]Foster, B. R., "The siege of Armanum.", Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society, vol. 14, no. 1, pp 27-36, 1982

- ISBN 1897750625.

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr, "Two Sargonic Seals from Urusagrig and the Question of Urusagrig’s Location", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 112, no. 1, pp. 1-10, 2022 https://doi.org/10.1515/za-2021-2001

- ^ Archi, Alfonso, and Maria Giovanna Biga, "A Victory over Mari and the Fall of Ebla", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 55, pp. 1–44, 2003

- ^ Sharlach, Tonia, "Princely Employments in the Reign of Shulgi", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-68, 2022

- ^ [6]Kraus, Nicholas Larry, "Tuṭṭanabšum: Princess, Priestess, Goddess", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 85-99, 2020

- ^ Michalowski, Piotr, "Tudanapšum, Naram-Sin and Nippur", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 173–76, 1981

- ^ Victory Stele of Naram-Sin at the Louvre

- ^ Winter, Irene, et al., "Tree (s) on the mountain. Landscape and territory on the victory stele of Naram-Sîn of Agade." Landscapes. Territories, frontiers and horizons in the ancient Near East", Papers presented to the XLIV Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Venezia, 7-11 July 1997. Part I: Invited lectures, pp. 63-72, 1999

- ^ [7]Van Dijk, Renate Marian, "The standards on the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin", Journal for Semitics 25.1, pp. 33-50, 2016

- ^ Winter, Irene J.. "How Tall Was Naram-Sîn’s Victory Stele? Speculation on the Broken Bottom". Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen, edited by Erica Ehrenberg, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, 2021, pp. 301-312

- ISBN 0-534-64095-8.

- ^ J. de Morgan, "Description des objects d'art. Stele Triomphale de Naram-Sin", MDP 1, Paris, pp. 144-158, 1900

- ISBN 9781118718230.

- ^ [8]J. P. Naab, E. Unger, "Die Entdeckung der Stele des Naram-Sin in Pir Hüseyin", Istanbul Asariatika Nesriyati XII, 1934

- ^ JSTOR 4171539.

- ^ "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ [9]Fuad Basmachi, "An Akkadian Stele", Sumer, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 116-119, 1954

- ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- ^ P.-A. Beaulieu, "The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 556–539 BC", (Yale Near Eastern Researches 10). New Haven and London, 1989

- ^ Weiershäuser, Frauke and Novotny, Jamie, "Nabonidus — Babylonia", The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 52-185, 2020

- ^ [10]Rawlinson, Henry Creswicke, "A selection from the miscellaneous inscriptions of Assyria and Babylonia", in The Cuneiform inscriptions of Western Asia, vol. 5, London, 1884

- ^ "The Dark Pictures Anthology: House of Ashes Preview". The Sixth Axis (TSA). 27 May 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ British Museum G56/dc11 BM 118553

- ^ "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ [11]S. Smith, "Early History of Assyria", London, 1928

- ^ Seton Lloyd, "The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: From the Old Stone Age to the Persian Conquest", Thames & Hudson, Inc, New York 1978

- ISBN 9782021291636.

Further reading

- Al-Hussainy, Abbas Ali Abbas, "The civilized achievements of the Akkadian king Naram-Sin A Research in his Artistic Remains and The Date Formulas", ISIN Journal 3, 2022

- Boissier, Alfred, "Inscription de Naram-Sin", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 157–64, 1919

- Foster, B. R., "Naram-Sin in Martu and Magan", ARRIM 8, pp. 25–44, 1990

- Glassner, J. J., "Naram-Sîn Poliorcète. Les avatars d'une sentence divinatoire", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 3–10, 1983

- Grayson, A. Kirk, and Edmond Sollberger, "L’insurrection générale contre Narām-Suen", RA70, pp. 103–128, 1976

- Lafont, Bertrand, "Une plaque en argile portant une inscription de Naram-Sin d'Agadé", The Third Millennium. Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik, hrsg. v. Arkhipov, Ilya, Kogan, Leonid, Koslova, Natalia (Cuneiform Monographs 50), pp. 408-416, 2020

- Piotr Michalowski, "New Sources concerning the Reign of Naram-Sin", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 233–246, (Oct., 1980)

- Nassouhi, Essad, "Un vase en albatre de Naram - Sin", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 91–91, 1925

- [12]A. Poebel, "The ‘Schachtelsatz’ Construction of the Naram-Sîn Text RA XVI 157f.", Miscellaneous Studies, AS 14; Chicago, pp.23–42, 1947

- Powell, Marvin A., "Narām-Sîn, Son of Sargon: Ancient History, Famous Names, and a Famous Babylonian Forgery", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 81, no. 1-2, pp. 20-30, 1991

- Salgues, E., "Naram-Sin's conquests of Subartu and Armanum", Akkade is King. A collection of papers by friends and colleagues presented to Aage Westenholz on the occasion of his 70th birthday 15th of May 2009, hrsg. v. Gojko Barjamovic (Uitgaven van het Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten te Leiden 118), pp. 253-272, 2011

- Steinkeller, Piotr, "The Roundlet of Naram-Suen", History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 158-164, 2017

- F.Thureau-Dangin, Une inscription de Naram-Sin", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 199–200, 1911

![Alabaster vase in the name of "Naran-Sin, King of the four regions" '(𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪 𒈗 𒆠𒅁𒊏𒁴 𒅈𒁀𒅎 DNa-ra-am DSîn lugal ki-ibratim arbaim), limestone, c. 2250 BC. Louvre Museum AO 74.[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Vase_in_the_name_of_Naran-Sin_King_of_the_four_region%2C_limestone%2C_circa_2250_BCE.jpg/96px-Vase_in_the_name_of_Naran-Sin_King_of_the_four_region%2C_limestone%2C_circa_2250_BCE.jpg)

!["Naran-Sin, King of the four regions" '(𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪 𒈗 𒆠𒅁𒊏𒁴 𒅈𒁀𒅎 DNa-ra-am DSîn lugal ki-ibratim arbaim), limestone, c. 2250 BC. Louvre Museum AO 74.[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Naram-Sin%2C_King_of_the_Four_quarters_of_the_World.jpg/150px-Naram-Sin%2C_King_of_the_Four_quarters_of_the_World.jpg)

![This bronze head traditionally attributed to Sargon is now thought to actually belong to his grandson Naram-Sin.<r[48]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Bronze_head_of_an_Akkadian_ruler%2C_discovered_in_Nineveh_in_1931%2C_presumably_depicting_either_Sargon_or_Sargon%27s_grandson_Naram-Sin_%28Rijksmuseum_van_Oudheden%29.jpg/104px-thumbnail.jpg)

![Fragment of a stone bowl with an inscription of Naram-Sin, and a second inscription by Shulgi (upside down). Ur, Iraq. British Museum.[57][58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1e/Fragment_of_a_stone_bowl_with_2_inscriptions%2C_from_Ur%2C_Iraq._British_Museum.jpg/150px-Fragment_of_a_stone_bowl_with_2_inscriptions%2C_from_Ur%2C_Iraq._British_Museum.jpg)

![Rock relief image at Darband-i-Gawr originally thought to be of Naram-Sin but since in dispute.[59][60]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Naram-Sin_Rock_Relief_at_Darband-iGawr_%28extracted%29.jpg/92px-Naram-Sin_Rock_Relief_at_Darband-iGawr_%28extracted%29.jpg)

![Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, c. 2230 BC. It shows him defeating the Lullibi, a tribe in the Zagros Mountains, and their king Satuni, trampling them and spearing them. Satuni, standing right, is imploring Naram-Sin to save him.[61] Naram-Sin is also twice the size of his soldiers.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/67/Stele_Naram_Sim_Louvre_Sb4.jpg/150px-Stele_Naram_Sim_Louvre_Sb4.jpg)