Nieuport 16

| Nieuport 16 C.1 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Role | Fighter |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | Nieuport, Dux |

| Designer | Gustave Delage |

| First flight | 1916 |

| Introduction | March 1916[1] |

| Retired | 1917 |

| Primary users | |

| Produced | 1916 |

| Number built | unknown |

| Developed from | Nieuport 11 |

| Developed into | Nieuport 17 |

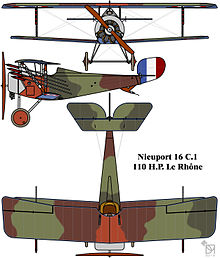

The Nieuport 16 C.1 (or Nieuport XVI C.1 in contemporary sources)

Development

The Nieuport 16 was an improved Nieuport 11 developed in 1916, with a strengthened airframe powered by a more powerful 110 hp (82 kW) Le Rhône 9J rotary engine.[2] Visible differences included a headrest for the pilot and a larger aperture in front of the "horseshoe" cowling.[2] The Nieuport 16 was an interim type pending the delivery of the slightly larger Nieuport 17 C.1, whose design was begun in parallel with the 16, and which remedied the 16's limitations, as well as improving performance. Additional Nieuport 16s were built under licence in Russia by Dux, which also added a headrest to the Nieuport 11s they were still building, making identification more difficult.[3]

As with the Nieuport 11, no synchronizer was initially available, which meant the Nieuport 16's Lewis machine gun was similarly mounted to fire over the propeller. Some of the first examples delivered to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) were fitted with a Lewis mounted on the cowl in front of the pilot and fitted with an Alkan-Hamy synchronization gear: however the Lewis's open bolt firing cycle resulted in an unpredictable rate of fire which played havoc with the timing and these soon reverted to the overwing mounts.[4][5] The Alkan-Hamy gear was then applied much more successfully to a fuselage-mounted Vickers machine gun, which was used on later French Nieuport 16s. However this configuration made the aircraft dangerously nose-heavy and increased the wing loading which compromised manoeuvrability. The British would continue with the overwing gun for all of their Nieuport scouts, and developed their own Foster mounting to improve on the numerous French designs.[5] Although used widely on later Nieuport types, the Nieuport 16 was used to test the initial design. Clearing gun jams and replacing ammunition drums in flight remained challenging though, and the drums still limited ammunition supply even after the British introduced a new "double" 98 round drum.

Some Nieuport 16s were fitted to fire

Operational history

As an interim type bridging the gap between the preceding Nieuport 11 and the more sophisticated Nieuport 17, it rarely equipped entire units by itself in French service, but was operated alongside both types, as well as the two seat Nieuport 12,[7] and even Nieuport 10s. Its period of ascendancy would begin shortly after the start of the Battle of Verdun and encompassed the entire Battle of the Somme, both battles that set records for their duration and staggeringly large casualty lists.

One of many results of Verdun was French experimentation with camouflaging aircraft, which included using single overall colours including horizon blue and tan on Nieuport 11s, and culminated with a 4 colour disruptive camouflage pattern that was standardized on later Nieuport 11s, and used on almost all of the Nieuport 16s.

The same period also coincided with the greatest use of the first air-air rockets, the Le Prieur. Although erratic and difficult to aim, they were successfully used against German Drachen kite balloons.[6] In their first operational deployment, eight aces including Nungesser, Guiguet and Chaput were specially trained by Le Prieur in their use, and in an early morning attack on 22 May 1916, managed to down six balloons in short order, panicking the German authorities into lowering the remainder along a 100 km (62 mi) stretch of the front lines, blinding the German Army in time for the first French counter-attack on Fort Douaumont.[8] Le Prieurs were also occasionally used against ground targets, the first recorded instance of an air to ground rocket attack being on 29 June 1916, when a roving Nieuport 16 equipped with Le Prieur rockets found a large ammunition dump, and blew it up.[9]

One of the first pilots to be officially recognized as an ace and dubbed "The Sentinel of Verdun",

The

The Imperial Russian Air Service also operated a relatively small number of Nieuport 16s while they also awaited the arrival of the Nieuport 17, however surviving records are not clear how many as they didn't distinguish between the two types, and referred to both as Nieuport 16s.[15]

Operators

- Aviation Militaire Belge

- Aéronautique Militaire

- Escadrille N.12[7]

- Escadrille N.23[7]

- Escadrille N.31[7]

- Escadrille N.38[7]

- Escadrille N.48[7]

- Escadrille N.49[7]

- Escadrille N.57[7]

- Escadrille N.68[7]

- Escadrille N.73[7]

- Escadrille N.75[7]

- Escadrille N.77[7]

- Escadrille N.102[7]

- Escadrille N.112[7]

- Escadrille N.124[7]

- Groupement de Combat de Somme

- Groupement de Chasse Cachy

- Aéronautique Navale

- Escadrille de chasse terrestre du CAM de Dunkerque - operated one Nieuport 16, N1354 from June 1916 to July 1917.[17]

- Imperial Russian Air Force - some built under licence by Dux

- Royal Flying Corps - operated 25 Nieuport 16s delivered from 16 April to 6 August 1916.[19]

- No. 64 Squadron RFC[7]

Specifications (Nieuport 16 C.1)

Data from Davilla, 1997, p.378, Pommier, 2002, p.171 and Durkota, 1995, p.358

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 5.640 m (18 ft 6 in)

- Upper wingspan: 7.520 m (24 ft 8 in)

- Upper Chord: 1.200 m (3 ft 11.2 in)

- Wing sweep: 3° 30'[21]

- Lower wingspan: 7.400 m (24 ft 3 in)

- Lower Chord: 0.700 m (2 ft 3.6 in)

- Height: 2.40 m (7 ft 10 in)

- Wing area: 13.30 m2 (143.2 sq ft)

- Airfoil: Type N[21]

- Empty weight: 375 kg (827 lb)

- Gross weight: 550 kg (1,213 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 45 kg[22]

- Undercarriage track: 1.60 m (5 ft 3 in)[21]

- Powerplant: 1 × Le Rhône 9J 9-cylinder rotary engine, 82 kW (110 hp) (nominal rated power, not measured power)

- Propellers: 2-bladed Levasseur 482 wooden propeller[21]

Performance

- Maximum speed: 165 km/h (103 mph, 89 kn) at sea level

- 156 km/h (97 mph; 84 kn) at 2,000 m (6,600 ft)

- Endurance: 2 hours

- Service ceiling: 4,800 m (15,700 ft)

- Time to altitude:

- 5 minutes 50 seconds to 2,000 m (6,600 ft)

- 10 minutes 10 seconds to 3,000 m (9,800 ft)

- Wing loading: 39.6 kg/m2 (8.1 lb/sq ft) [22]

- Power/mass: 4.9 kg/hp[22]

Armament

- 1 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis machine gun OR 1 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers machine gun

- 8 × air to air Le Prieur rockets for use against observation balloons (optional)

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of military aircraft of France

- List of aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps

- List of military aircraft of the Entente Powers in World War I

References

Notes

- ^ The C in the designation indicates that it is a chasseur or fighter, and the 1 indicates the number of crew members.

Citations

- ^ Sanger, 2002, p.103

- ^ a b Durkota, 1995, p.353

- ^ Bruce, 1994, p.20

- ^ a b c d Bruce, 1992, p.327

- ^ a b Sanger, 2002, p.104

- ^ a b Guttman, 2005, p.9

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Davilla, 1997, p.378

- ^ Guttman, 2005, p.12

- ^ Albin, Denis. "Escadrille MF 62 - N 62 - SPA 62". Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ "Charles Eugene Jules Marie Nungesser". www.theaerodrome.com. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ Albin, Denis. "Escadrille N 68 - SPA 68". Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Franks, 2000, p.11

- ^ a b Bruce, 1992, p.326

- ^ Spooner, 1916, p.587

- ^ a b Bruce, 1994, p.7

- ^ Knight, 2011, p.44

- ^ Morareau, 2002, p.66

- ^ a b c Durkota, 1995, p.387

- ^ "Nieuport".

- ^ a b c d e Bruce, 1992, p.328

- ^ a b c d Pommier, p.171

- ^ a b c Durkota, 1995, p.358

Bibliography

- Bruce, J. M. (1992). The Aeroplanes of the Royal Flying Corps Military Wing. Bridgend, UK: Putnam Aeronautical Books. ISBN 0851778542.

- Bruce, J. M. (1988). Nieuport Aircraft of World War One - Vintage Warbirds No 10. London, UK: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 0-85368-934-2.

- Bruce, J. M. (1994). Nieuport Fighters - A Windsock Datafile Special Volumes 1 & 2. Herts, UK: Albatros Publications. ISBN 978-0948414541.

- Bruce, J. M. (n.d.). "Those Classic Nieuports". Air Enthusiast Quarterly. No. 2. pp. 137–153. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Davilla, Dr. James J.; Soltan, Arthur (1997). French Aircraft of the First World War. California: Flying Machines Press. ISBN 978-1891268090.

- Durkota, Alan; Darcey, Thomas; Kulikov, Victor (1995). The Imperial Russian Air Service — Famous Pilots and Aircraft of World War I. California: Flying Machines Press. ISBN 0-9637110-2-4.

- Franks, Norman (2000). Nieuport Aces of World War 1. Osprey Aircraft of the Aces 33. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-961-1.

- Guttman, Jon (2005). Balloon-busting aces of World War 1. Osprey aircraft of the aces 66. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1841768779.

- Knight, Brian (2011). Nieuports in RNAS, RFC and RAF Service. London, UK: Cross & Cockade International. ISBN 978-0955573439.

- Kowalski, Tomasz J (2003). Nieuport 1-27. Lublin, Poland: Kagero. ISBN 978-8389088093.

- Morareau, Lucien (2002). Les Aeronefs de l'Aviation Maritime (in French). Paris, France: ARDHAN (Association pour la Recherche de Documentation sur l'Histoire de l'Aeronautique Navale. ISBN 2-913344-04-6.

- Pommier, Gerard (2002). Nieuport 1875-1911 — A biography of Edouard Nieuport. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0764316241.

- Rosenthal, Léonard; Marchand, Alain; Borget, Michel; Bénichou, Michel (1997). Nieuport 1909-1950 Collection Docavia Volume 38 (in French). Clichy Cedex, France: Editions Lariviere. ISBN 978-2848900711.

- Sanger, Ray (2002). Nieuport Aircraft of World War One. Wiltshire, UK: Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1861264473.

- Stanley Spooner, ed. (13 July 1916). "The R.F.C. Inquiry". Flight. Vol. VIII, no. 28/394. Royal Aero Club. p. 587. Retrieved 8 June 2019.