Polis

Ancient Greek Polis

πόλις | |

|---|---|

Acropolis of Athens, a noted polis of classical Greece. The polis was the whole city, which had its own walls. Shown is a part of the polis, the akro-polis, "city heights," which was never alone regarded as its own city. The origins of the settlement are lost in prehistoric times. Also included in the classical Athenian polis were suburban locations in the region of Attica, such as the port, Piraeus. | |

| Etymology: "walls" | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Republic, or commonwealth. The ultimate authority was considered to reside in the citizenry, the demos, despite the broad variation in the form of the administration. |

| • Body | The assembly, or ekklesia, although in the more autocratic forms of administration, it met rarely. The day-to-day governing was performed by magistrates, called archons. |

| Area | |

| • max area of 60% of poleis | 100 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| • max area of 80% of poleis | 200 km2 (80 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 7,500,000+ |

| Demonym(s) | Dēmos in the Attic-Ionic dialects or dãmos in the Doric. The demonym was formed by producing the name of a people from the name of the polis. For example, the polis of Athens was named Athenai after the goddess Athena; hence the demos was the Athenaioi, "the Athenians."[d] |

Polis (/ˈpɒlɪs/, US: /ˈpoʊlɪs/; Greek: πόλις, Greek pronunciation: [pólis]), plural poleis (/ˈpɒleɪz/, πόλεις, Greek pronunciation: [póleːs]), means ‘city’ in ancient Greek. The modern Greek word πόλη (polē) is a direct descendant of the ancient word and roughly means "city" or an urban place. However, the Ancient Greek term that specifically meant the totality of urban buildings and spaces was asty (ἄστυ), rather than polis.

The ancient word polis had socio-political connotations not possessed by the modern. For example, today's πόλη is located within a χώρα (khôra), "country," which is a πατρίδα (patrida) or "native land" for its citizens.[3] In ancient Greek, the polis is the native land; there is no other. It has a constitution and demands the supreme loyalty of its citizens. χώρα is only the countryside, not a country. Ancient Greece is not a sovereign country, but is a territory occupied by Hellenes, people who claimed as their native language some dialect of ancient Greek.

Poleis didn't only exist within the area of the modern Republic of

The ancient Greek world was split between homeland regions and colonies. A colony was generally sent out by a single polis to relieve the population or some social crisis or seek out more advantageous country. It was called a metropolis or "mother city." The Greeks were careful to identify the homeland region and the metropolis of a colony. Typically a metropolis could count on the socio-economic and military support of its colonies, but not always. The homeland regions were located on the Greek mainland. Each gave an ethnic or "racial" name to its population and poleis. Acarnania, for example was the location of the Acarnanian people and poleis.[4] A colony from there would then be considered Acarnanian, no matter how far away from Acarnania it was. Colonization was thus the main method of spreading Greek poleis and culture.

Ancient Greeks did not reserve the term polis solely for Greek-speaking settlements. For example, Aristotle's study of the polis names also Carthage, comparing its constitution to that of Sparta. Carthage was a Phoenician-speaking city. Many nominally Greek colonies also included municipalities of non-Greek speakers, such as Syracuse.[e]

The problem of defining the polis

The word polis is used in the first known work of Greek literature, the Iliad, a maximum of 350 times.[5][f] The few hundred ancient Greek classical works on line at the Perseus Digital Library use the word thousands of times. The most frequent use is Dionysius of Halicarnassus, an ancient historian, with a maximum of 2943. A study of inscriptions found 1450 that use polis prior to 300 BC, 425 Athenian and 1025 from the rest of the range of poleis. There was no difference in meaning between literary and inscriptional usages.[6]

Polis became loaded with many incidental meanings.[7] The major meanings are "state" and "community."[8] The theoretical study of the polis extends as far back as the beginning of Greek literature, when the works of Homer and Hesiod in places attempt to portray an ideal state. The study took a great leap forward when Plato and the academy in general undertook to define what is meant by the good, or ideal, polis.

Books II–IV of The Republic are concerned with Plato addressing the makeup of an ideal polis. In The Republic, Socrates is concerned with the two underlying principles of any society: mutual needs and differences in aptitude. Starting from these two principles, Socrates deals with the economic structure of an ideal polis. According to Plato there are five main economic classes of any polis: producers, merchants, sailors/shipowners, retail traders and wage earners. Along with the two principles and five economic classes, there are four virtues. The four virtues of a "just city" are wisdom, courage, moderation and justice. With all of these principles, classes and virtues, it was believed that a "just city" (polis) would exist.

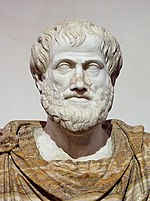

Breaking away from Plato and the academy, a professor there, Aristotle, founded his own school, the Lyceum, a university. One of its strongest curricula was political science, which Aristotle invented. He dispatched students over the world of the polis to study the society and government of individual poleis, and bring the information back to document, placing the document in a political science section of the library. Unfortunately only two documents have survived, Politics and Athenian Constitution. These are a part of any political science curriculum today.

Both major ancient Greek philosophers were concerned with elucidating an existing aspect of the society in which they lived, the polis. Plato was more interested in the ideal; Aristotle, the real. Both had a certain view of what the polis was; that is, a conceptual model. All models must be tested, by definition. Aristotle, of course, could send direct observers. The only way to know a polis now is through study of the ancient literature (philology), and to some extent archaeology. There are thousands of pages of writing and certainly thousands of sites. The problem is to know what information to select for a model and what to neglect as probably irrelevant.

Classical studies of the last few hundred years have been relatively stable in their views of the polis, relying basically on just a few models: the concept of a city-state, and Fustel de Coulange's model of the ancient city. However, no model ever seems to resolve all the paradoxes or provide for every newly considered instance. The question is not whether poleis can be found to fit a particular model (some usually can), but whether the model covers all the poleis, which, apparently, no model ever has, even the ancient ones.[9][g] The re-defining process continues.[10]

The Copenhagen study rejects either model and proposes instead the microstate. Some few scholars have become totally cynical, rejecting the idea that any solution has been or can be found. This argument places polis in the same category of Plato's indefinable abstracts, such as freedom and justice. However, there is a practical freedom and a practical justice, though not theoretically definable, and the ancient authors must mean something consistent when they use the word polis. The problem is to find it.

Limitations of the failed modern models

The subjective element of a model

In modern historiography of the ancient world πόλις is often transliterated to polis without any attempt to translate it into the language of the historiographer. For example, Eric Voegelin wrote a work in English entitled "The World of the Polis."[11] In works such as this the author intends to define polis himself; i.e., to present a model of society from one or more of a list of ancient Greek cities (poleis) culled from ancient Greek literature and inscriptions.

For example, Voegelin describes a model in which "town settlements" existed in the Aegean for a few thousand years prior to the Dorian invasions, forming an "aggregate, the pre-Doric city."[12] This type of city is not to be regarded as "the Hellenic type of the polis". The Greeks set adrift by the Dorian invasions countered by joining (synoecism) to form the Hellenic poleis. The polis can thus be dated to this defensive resettlement period (the Dark Age). Quite a few poleis fit the model, no doubt, which was widely promulgated in the 20th century.

Classical Athens, however, is a paradox in this model, to which Voegelin has no answer. He says "in the most important instance, that of Athens, the continuity between the Aegean settlement and the later polis seems to have been unbroken". It seems a matter of simple logic that if Athens was a Hellenic polis in the time of the Hellenic poleis and was continuous with the pre-Doric city phase, then pre-Doric Athens must have been a Hellenic polis even then. The model fails in its chief instance.

A second approach to the modelling of the polis is not to use the word polis at all, but to translate it into the language of the historiographer. The model is thus inherent in the translation, which has the disadvantage of incorporating a priori assumptions as though they were substantiated facts and were not the pure speculations they actually are.

Problems with Coulanges' ancient city

One of the most influential of these translative models was the French

Coulanges' confidence that the Greek and Italic cities were the same model was based on the then newly discovered

From the analogy Coulanges weaves a tale of imaginary history. Families, he asserts, originally lived dispersed and alone (a presumption of Aristotle as well). When the population grew to a certain point, families joined into phratries. Further growth caused phratries to join into tribes, and then tribes into a city. In the city the ancient tribes remained sacrosanct. The city was actually a confederacy of ancient tribes.[15]

Coulange's tale, based on the fragmentary history of priesthoods, does not much resemble the history of cities such as it survives.

There were no families, no phratries, no tribes, except among the already settled Latins, Greeks, and Etruscans. The warriors acquired a social structure by kidnapping the nearby Italic Sabines ("the Rape of the Sabine Women") and settling the matter by agreeing on a synoecism with the Sabines also, who were Latins. Alba Longa was ignored, later subdued. The first four tribes were not the result of any previous social evolution. They were the first municipal division of the city manufactured for the purpose. They were no sort of confederacy. Rome initially was ruled by Etruscan kings.

Problems with the city-state

Coulanges work was followed by the innovation of the English city-state by W. Warde Fowler in 1893.[17] The Germans had already invented the word in their own language: Stadtstaat, "city-state," referring to the many one-castle principates that abounded at the time. The name was applied to the polis by Herder in 1765. Fowler anglicised it: "It is, then, a city-state that we have to deal with in Greek and Roman history; a state in which the whole life and energy of the people, political, intellectual, religious, is focused at one point, and that point a city."[18] He applied the word polis to it,[19] explaining that "The Latin race, indeed, never realised the Greek conception ... but this was rather owing to their less vivid mental powers than to the absence of the phenomenon".[19]

Polis is thus often translated as ‘city-state’. The model, however, fares no better than any other. City-states no doubt existed, but so also did many poleis that were not city-states. The minimum semantic load of this hyphenated neologism is that the referent must be a city and must be a sovereign state. As a strict rule, the definition fails on its exceptions.[20] A polis may not be urban at all, as was pointed out by Thucydides[21][i] regarding the "polis of the Lacedaemonians", that it was "composed of villages after the old fashion of Hellas". Moreover, around the five villages of Lacedaemon, which had been placed in formerly Achaean land, were the villages of the former Achaeans, called the perioeci ("dwellers round").[j] They had been left as supposedly free poleis by the invaders, but they were subject to and served the interests of the Dorian poleis.[22] They were not city-states, failing the criterion of sovereignty.[23]

Lacedaemon by the city-state rule thus falls short of being a polis. The earlier Achaean acropolis stood at the edge of the valley and was decrepit and totally unused. Lacedaemon had neither a city nor an acropolis, but all the historiographers referred to it as a polis. The rule of the city-state persisted until late in the 20th century, when the accumulation of mass data and sponsored databases made possible searches and comparisons of multiple sources not previously possible, a few of which are mentioned in this article.

Hansen reports that the Copenhagen Centre found it necessary to "dissociate the concept of polis from the concepts of independence and autonomia." They were able to define a class of "dependent poleis" to consist of 15 types, all of which the ancient sources call poleis, but were not entirely sovereign, such as cities that had been independent, but were later synoecized into a larger polis, new colonies of other poleis, forts, ports, or trading posts some distance removed from their mother poleis, poleis that had joined a federation with binding membership, etc. The perioeci were included in this category.[24]

When the models are set aside as primary sources (which they never were) it is clear that historiography must be founded on what the authors and inscriptions say.[k] Moreover, there is a time window for the active polis. The fact that polis was used in the Middle Ages to translate civitas does not make these civitates into poleis. The Copenhagen Study uses quite a few evidential indications of a probable polis, in addition to the manuscripts and inscriptions, some of which are victory in the Panhellenic Games,[26] participation in the games,[27] having an official agent, or proxenos, in another polis,[26] presence of civic subdivisions, presence of citizens and a Constitution (Laws).

The main features of the ancient Greek models

Aristotle's polis

Modern theorists of the polis are theorizing under a major disadvantage: their topic has not been current for thousands of years. It is not left to the moderns to redefine polis as though it were a living institution. All that remains to ask is how the ancients defined it. It is not to be redefined now; for example, a polis is not a list of architectural features based on ruins. Any community might have those. Moderns can only ask, what did the ancient Greeks think a polis is. Whatever they thought must per force be so, as they invented the term. There were no doubt many ancient experts on the polis, but time has done its work. The one surviving expert, Aristotle, is thus an indispensable resource.

A polis is identified as such by its standing as polis among the community of poleis. Poleis have ambassadors, can join or host the Hellenic Games, etc. According to Aristotle, their most essential characteristics are those that, if changed, would result in a different polis. These are three. A polis has a particular location, population, and constitution (politeia). For example, if a polis moves en masse, receives a different form of government, or an influx of new population, it is not the same polis.[29]

Aristotle expresses two main definitions of polis, neither of which is possible as stated. In the second (see below for the first) a polis is "a collection of citizens...." (Book III I 2). If they already are citizens, then there is no need for anyone to collect to create a polis, as it already exists. If they are not citizens then they cannot be defined as a polis and cannot act as such. Aristotle's only consistent meaning is that at the moment of collecting together a population creates a polis of which they are now citizens.

This moment of creation, however long it might be,[l] is a logical necessity; otherwise, the citizenship recedes indefinitely into the unknown past. All current citizenships must have had their first moments, typically when the law-maker had gotten his laws ratified, or the colony had broken with the metropolis.

The ancient writers referred to these initial moments under any of several words produced with the same prefix, sunoik- (Latinized synoec-), "same house," meaning objects that are from now on to be grouped together as being the same or similar. It is a figure of speech, the most general instance being sunoik-eioun, "to be associated with",[30] its noun being sunoik-eiosis, the act of association.

A second verb, sunoik-ein,[31] "to live together," can mean individuals, as in marriage, or conjointly, as in a community. The community meaning appears in Herodotus. A closely related meaning, "to colonize jointly with," is found there also, and in the whole gamut of historical writers, Xenophon, Plato, Strabo, Plutarch; i.e., more or less continuously through all periods from Archaic to Roman. Associated nouns are sunoik-ia,[32] sunoik-esion, sunoik-idion, sunoik-eses, sunoik-isis, a multiplication to be expected over centuries of a single language. These can all mean community in general, but they have two main secondary meanings, to institute a community politically or to enlarge the buildings in which it resides.

Finally in the Classical Period and later, the -z-/-s- extension began to be used, as evidenced in Thucydides, Xenophon, and Plutarch: sunoik-izein,[33] "combine or join into one city," with its nouns sunoik-isis and sunoik-ismos,[34] "founding a city", from which the English scholarly term synoecism derives. All poleis looked back to a synoecism under any name as their source of politeia. Not all settlements were poleis; for example, an emporion, or "market reserved for foreign trade", might be part of a polis or out on its own.[35]

In any particular synoecism recorded by either ancient or modern epigraphists a major problem has been to fit the model credibly to the instance. For example, Thucydides refers to Spartan lack of urbanity as "not synoecised", where synoecism is the creation of common living quarters (see above). Here apparently it means only the building of a central urban area. The reader of Plutarch knows that another synoecism existed, one instituted by Lycurgus, founder of the military state. The single overall synoecism is apparently double, one for the facilities, missing in this story, and one for the constitution.

He uses the same word to describe the legal incorporation of the settlements around Athens into the city by King Theseus, even though no special building was required. The central polis already existed.[36][m] In this story also there is a duality of synoecism with an absent change of physical facilities. Apparently a synoecism can be of different types, the selection of which depends on the requirements of the sunoikisteres.[37] Lippman applies two concepts previously current, the political synoecism and the physical synoecism, to events at the polis of Pleuron (Aetolia) described by Strabo.[38] Pleuron, in danger of being sacked by the Macedonians, was officially moved up the slope of a nearby mountain, walled in, and named Newer Pleuron. This act was a physical synoecism. After the Macedonian threat vanished the former location was reinhabited and called Old Pleuron. The old and the Newer were united with a political synoecism.

The polis as community

The first sentence of Politics asserts that a polis is a community (koinonia). This is Aristotle's first definition of polis (for the second, see above). The community is compared to a game of chess. The man without community is like an isolated piece (I.9). Other animals form communities, but those of men are more advantageous because men have the power of speech as well as a sense of right and wrong, and can communicate judgements of good or bad to the community (I.10). A second metaphor compares a community to a human body: no part can function without the whole functioning (I.11). Men belong to communities because they have an instinct to do so (I.12).

The polis is a hierarchy of community. At the most subordinate level is the family (oikia), which has priority of loyalty over the individual. Families are bound by three relationships: husband to wife, owner to slave,[n] and father to children. Thus slaves and women are members of the polis.[o] The proper function of a family is the acquisition and management of wealth. The oikia is the primary land-holder.[p]

The koinonia, then, applied to property, including people. As such it is just as impossible as the collection of citizens mentioned previously, which cannot be both all the citizens and simultaneously a collection of some of the citizens. Similarly property shared by all cannot be shared by men who do not own it. These fictions led to endless conflict between and within poleis as the participants fought for citizenship they did not have and shares they did not own.

A village (kome) is a community of several families (I.2). Aristotle suggests that they came from the splitting (apoikia, “colonization”) of families; that is, one village contains one or more extended families, or clans. A polis is a community of villages, but there must be enough of them to achieve or nearly achieve self-sufficiency. At this point of his theorization, Aristotle turns the “common” noun stem (koino-) into a verb, koinonizein, “to share” or “to own in common.” He says: “A single city occupies a single site, and the single city belongs to its citizens in common.”

Aristotle's description fits the landscape archaeology of the poleis in the Copenhagen Study well.[39] The study defines settlement patterns of first-, second-, and third-order. The third, dispersed, is individual oikiai distributed more or less evenly throughout the countryside. The other two orders are nucleated, or clustered.[40] 2nd-order settlements are the komai, while the 1st order is the poleis. Approaching the polis from the outside of an aerial photograph one would pass successivle orders 3, 2, and 1.

By the end of Book I of Politics Aristotle (or one of the other unknown authors) finishes defining the polis according to one scheme and spends the next two books trying to tie up loose ends. It is generally agreed that the work is an accumulation of surviving treatises written at different times, and that the main logical break is the end of Book III. Books I, II, and III, dubbed "Theory of the State" by Rackham in the Loeb Edition,[41] each represents an incomplete trial of the "Old Plan." Books !V, V, and VI, "Practical Politics," are the "New Plan." Books VII and VIII, "Ideal Politics," contains Aristotle's replacement of Plato's ideology, openly called "communist" by modern translators and theoreticians, of which Aristotle is highly critical.[q]

The Theory of the State is not so much political by today's definition. The politics are covered by the New Plan. The topic of the Old Plan is rather society, and is generally presented today in sociology and cultural anthropology. At the end of Book III, however, Aristotle encounters certain problems of definition that he cannot reconcile through theorization and has to abandon the sociology in favor of the New Plan, conclusions resulting from research on real constitutions.

The difficulties with the Old Plan begin with the meaning of koinonizein, "to hold in common." Typically the authors of the Old Plan use the verb in such expressions as "those holding in common," "A holding in common," "the partnership," and the like, without specifying who is holding what or what the holding relationship implies.

In Book II Aristotle begins to face the problem. The "polis men," politai, translated as "citizens," must logically hold everything there is to hold, nothing, or some things but not others (II.I.2). In this sociological context politai can only be all the householders sharing in the polis, free or slave, male or female, child or adult. The sum total of all the specific holdings mentioned in the treatise amount to the anthropological sense of property: land, animals, houses, wives, children, anything to which the right of access or disposition is reserved to the owner. This also happens to be Plato's concept of property, not an accident, as Aristotle was a renegade Platonist. The polis, then, is communal property. The theory of its tenancy is where Aristotle and Plato differ sharply.[r]

Plato had argued that the relinquishing of property to form the polis is advantageous, and the maximum advantage is maximum possession of common property by a polis. The principle of advantage is unity. The more united, the more advantageous (compare the action of a lever, which concentrates advantage). The ideal commun-ity would be commun-ism, the possession of all property by the community. Personal property, such as wives and children, are included (II.1).[s]

Aristotle argues that this eminent domain of all property is actually a lessening of unity and would destroy the state. The individual is actually most united and effective; the polis the least. To take away the property and therefore the powers of the individual diminishes the state to nothing, as it is composed of citizens, and those citizens have been rendered null and void by the removal of their effectiveness. As an example Aristotle gives a plot of land, which owned by one man is carefully tended, but owned by the whole community belongs to no one and is untended.

The ideal state therefore is impossible, a mere logical construct accounting for some of the factors, but failing of others, which Aristotle's examples suffice to demonstrate. For example, in some hypothetical place of no polis, a buyer would apply to an individual builder for a house. In an ideal polis, he would apply to the state, which would send other members of the united polis to do the work. They would also be sent for any other task: plumbing, farming, herding, etc., as any task could be performed by any member. This view is contrary, as Aristotle points out, to the principle of

Aristotle says, "A collection of persons all alike does not constitute a state." He means that such a collection is not self-sufficient (II.1.4). He alleges the opposite: "components which are to make up a unity must differ in kind .... Hence reciprocal equality is the preservative of states, as has been said before in (Nichomachean) Ethics (1132b, 1133a)." In summary the argument there is "For it is by proportionate requital that the city holds together .... and if they cannot do so there is no exchange, but it is by exchange that they hold together."

In short Aristotle had stated two systems of property, one in which the polis holds everything, distributing it equally, and one in which some property is held in common but the rest is privately owned. As the former only leads to a bankrupt state, the latter must be the one that prevails. For survival the citizens of each city build a privately owned pool of diverse resources, which they can exchange for mutual ("reciprocal") benefit. The theory of equal reciprocity is nothing more than a statement that owners of diverse assets must make profitable deals with each other.[42]

In Book III Aristotle begins presentation of the New Plan. The Old Plans had concerned themselves with the sociology of the community, concluding that the family, or house, was the smallest unit of the state, and using the term citizen to mean any family members, slave or free, of any age. The discovery of reciprocal equality brought the realization that in the supposedly synoecized polis a large amount of unsynoecized property was a sine qua non of sufficiency and therefore of the polis. The Old Plan was abandoned and the state was defined again in the New Plan.

The presence of private property in the polis meant that it might be owned by foreigners (xenoi), raising questions of whether a single state existed there at all, or if it did, whose was it (III.I.12). Anyone might own the property of the city.[t] The whole purpose of synoecism was to create a single city for the benefit of the owners. These were the tribesmen of the villages. The need exists therefore to distinguish between citizens and others. The citizens can own common property, but the non-citizens, only private.

The polis as state

Polis is usually translated as "state." "Politics" is from the adjective politika formed on polis. It concerned the affairs of the polis and is approximately equivalent to statesmanship.[u] Politeia means what moderns mean by government. There are certain social activities that are generally agreed to be the concern of the whole community, such as justice and the redress of wrongs, public order, soldiering, and leadership of major events. The institutions that accomplish these goals are the government. It demands to be the object of greatest loyalty and the highest authority in the land. To this end laws are enacted to establish the government. Constitution as it is used of poleis signifies the social substructure, the people, and the laws of government.

Like polis, politeia has developed into a battery of meanings.[43] This battery reveals the semantic presence of a concept inseparable from any polis; namely, citizenship. The population of a polis must be divided into two types: citizens (politai),[44] and non-citizens. The latter are designated by no single term; "non-citizen" is a scholarly classification.[45] The concept of citizenship means more or less what it does today. Citizens are members of the polity and as such have both rights and obligations for which they are held responsible.

According to Aristotle, a citizen is "a person who is entitled to participate in government."[46] A government that is the hands of its citizens is defined today as a republic, which is one meaning of politeia.

However, a republic is not an exclusive form of government; it is a type of many forms; e.g., democracy, aristocracy, and even limited monarchy. If the people have nothing at all to say, then no republic, no polis exists, and they are not citizens. A polis was above all a constitutional republic. Its citizens on coming of age took an oath to uphold the law, according to Xenophon, usually as part of their mandatory military service.[47]

Citizenship was hereditary. Only families could provide young candidates for citizenship, but that did not mean they would be accepted. The government reserved the right to reject applications for citizenship or remove the status later. The politeia was a federal agency; there was nothing confederate about it. The duty officers did not have to obtain permissions from municipalities to exercise their sworn duties; they acted directly. If there were any legal consequences of these actions the accusers argued either that the magistrates had exceeded their authority or did not exercise it. The defense was a denial and an assertion of performance of duty.

The Copenhagen Study provides more definitive information about citizenship, and yet, it does not cover all the problems. Every polis once it had become so rejected the authority of all previous authoritative organizations and substituted new civic subdivisions, or municipalities, for them. Only citizens could belong to them, and only one per citizen. They were either regional (the deme) or fraternal (tribe, etc.). Furthermore, foreigners, slaves and women were excluded from them.[48]

Aristotle had said (Politics III.I.9) "Citizenship is limited to the child of citizens on both sides; that is, the child of a citizen father or of a citizen mother ...," which poses a difficulty in the model of the Copenhagen Study: since women cannot be citizens, there can't be any citizen mothers. Hansen proposes a dual citizenship, one for males, and one for females: "Female citizens possessed citizen status and transmitted citizen status to their children, but they did not perform the political activities connected with citizenship. They were astai rather than politai."[49]

The use of gyne aste, "female citizen," is rare, but it does appear in Herodotus with regard to the matrilineal system of Lycia. An astos is a male citizen, an aste, a female. One should therefore expect instances of the feminine of polites, which is politis,[50] and there are a few instances in major texts. Plato's Laws[51] speaks of politai (male) and politides (female) with reference to a recommendation that compulsory military training be applied to "not only the boys and men in the State, but also the girls and women...."[52]

In the model slaves also cannot be citizens. Although that seems to be generally true, there may be some exceptions. For example, Plutarch's Solon reports that Solon of Athens was called upon to form a new government in a social crisis, or stasis. The citizenry had been divided into a number of property classes with all the archonships going to the upper class. They had gone into the money-lending business requiring the lower-class borrowers to put up their persons or those of their families for collateral.[v] Defaulters were sold into slavery at home and abroad. Now the lower classes had united and were pushing through a redistribution of property. In a panic, the upper class called on Solon to write a new constitution allowing them to keep their lands.

Solon took the reins as chief archon. Invalidating the previous laws he cancelled the debts, starting with the large one owed him, made debt-slavery illegal, and set free the debt-slaves, going so far as to buy back Athenian citizens enslaved abroad. The price the rebels had to pay was that the upper class kept their land. The classes were re-defined. Now even the propertyless could attend the assemblies and sit on the juries. Apparently for that period in Athens citizens could be slaves, unless the whole story has not been told.[w]

Aristotle notes (II IV 12) that to maintain its population early Sparta "used to admit foreigners to their citizenship." A foreigner here is any person from any polis not under Spartan jurisdiction. Whether the practice implies double citizenship is not stated. If it does not, then a change of citizenship, or successful immigration, must be presumed. Otherwise there might be a conflict of interest.

A polis is a binding and irrevocable agreement between formerly separate populations to form a united and indissoluable commonwealth. Once the agreement takes effect all previous social arrangements become null and void. The polis demands first loyalty and exercises the power of life or death over its constituents. Its subdivisions and its laws must prevail.[x]

The organization of the government and the behavior of the constituents is governed by a constitution, or "laws." The constitution further defines which of the constituents are empowered to conduct government (citizens) and which not (non-citizens). Citizenship is not construed to mean constituency in the polis but is only a status within it. The laws of the polis are binding on all members, regardless of citizenship. The polis is therefore a commonwealth. The type of government, however, may vary.

City-states, therefore, are not necessarily poleis. There must be another, unifying element that made both Athens, Sparta, and the hundreds of other known settlements poleis. The answer is, so to speak, hiding in plain sight: the demonyms. Athens could not be a polis without the Athenians, Lacedaemon without the Lacedaemonians, etc. The general word for these united populations was demos in the Athenian dialect, damos originally and in the Spartan dialect.

Etymologically the demos is not a unification of pre-existing populations, but is a division of a united population into units. The Indo-European root is *dā-, "to divide," extended to *dā-mo-, "division of society."[53] Logically the division must be after the unification or there would be nothing to divide. How the whole can be a division is something of a problem. Demos can mean "the common people," but if these are meant to be opposed to the non-common people then the non-commons must be excluded from the polis, an unlikely conclusion, since it is the non-commons who usually have the most to do with the unification to begin with.

The dictionary entry for demos shows that "demos" had a wide range of meanings, including either the whole population of the polis or any municipality of it, but not both for the same polis.[54] The exact use depended on the polis; there was no one, universal way to synoecize into a polis. Athens especially used demos for "deme," a municipality. After noting "there was a grey area between polis and civic subdivision, be it a demos or a kome or a phyle...",[55] Hansen remarks "demos does not mean village but municipality, a territorial division of a people...."[56]

The inventory of poleis published by the Copenhagen Study lists the type of civic subdivisions for each polis for which it could be ascertained (Index 13). Names from a tribal structure are common, such as oikia, gene ("clans"), phratriai ("brotherhoods"), and phylai ("tribes"), never the whole range; i.e., clans without brotherhoods, or tribes withous clans, etc., suggesting that the terminology came from a previous social structure not then active. Only one or two are used; exceptionally, several systems of subdivisions superimposed.[57] Hansen suggests that these units, expressed generally in groups of komoi, were chosen because of their former role in synoecism, which also removed the former structures from service in favor of new municipalities.

In addition to these remnants of an earlier social organization are the demoi. All demoi are post-synoecic. Where the municipalities are demoi, they are the decision-making institution; i.e., the assembly (legislative branch) is of demoi. Those units also staff the boule (council) and the dikasterion (law courts). The fact that small poleis have only one demos suggests a way in which the demos could come to mean the whole population.

See also

- History of the polis

- The Other Greeks

- List of ancient Greek cities

- List of modern words formed from Greek polis

Notes

- ^ Up to the 21st century city-state was preferred. As not all the poleis are cities, microstate, which covers less than cities, is preferred now. Both names have the state problem: not all poleis are currently fully autonomous, but while microstate is generous in that regard, city-state is not.

- ^ Hansen is working from a sample of 869 poleis taken from the Copenhagen Study. Only 10% had a territory of over 500 km2 (190 sq mi). There were 13 super-states from Argos at 1,400 km2 (540 sq mi) to Syracuse at 12,000 km2 (4,600 sq mi). Athens had 2,500 km2 (970 sq mi). Lacedaemon had 8,400 km2 (3,200 sq mi). Of course, these estimates covering several hundred years and based on uncertain sources are highly approximate at best.

- ^ From the 869 samples of known poleis Hansen develops a table of population per size category and then expands the table proportionately until some of the items in the table hit verifiable numbers (shotgun blast). At an expansion to 1100 cities he obtains 7 million ancient Greeks excluding Epirus and Macedon, 7.5 including. As there were more than 1100 cities, these numbers represent a minimum possible. 3 million of these are in the 200 km2 (77 sq mi) to 500 km2 (190 sq mi) and 500 and over size categories, showing that then (as now) the Greeks preferred big-city environments even though most of the cities were of smaller size.

- ^ The Copenhagen Study refers to this ethnic reflex of the polis demonym as a "city-ethnic" often supplementing personal names. For details see Hansen 2004, p. 60

- ^ Hansen also mentions 75 "barbarian" cities that were called poleis by Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon. They include Tyre, Sidon, some Etruscan cities, Rome, Eryx and Egesta. Herodotus sometimes calls Persian and Scythian cities poleis, but Hansen points out that he tends to Hellenize names in those languages. For details see Hansen 2004, p. 36.

- ^ In Perseus' software to calculate the frequencies there is a margin of error of interpretation. The "maximum" interpretation takes every possibility as "polis."

- ^ Sakellariou runs through the various major models stating the pros and cons. Written prior to the Copenhagen Study, the book expresses dissatisfaction with former approaches to modeling and underscores the need for a wider programme of research, which in fact followed a few years later with the 10-year collaborative mission of the University of Copenhagen.

- ^ Hanson's view on Coulanges' view of the formation of a polis is "In my opinion the holistic view of the polis is skewed ...."[16]

- ^ The full passage illustrated along with its significance for the urbanization of a polis can be found at Brand, Peter J. "Athens & Sparta: Democracy vs. Dictatorship" (PDF). University of the People. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ The 19th- and early 20th-century view that perioeci and helots both came from the Achaeans was questioned because of Spartan abuse of the helots yet acceptance of perioeci into comradeship. Hammond in Cambridge Ancient History reiterates an alternative view that, while the helots did descend from the Achaeans, the perioeci were a mixture of Achaeans and Dorians who had settled in Laconia prior to the creation of a military state by the laws of Lycurgus in the late 9th century BC. Hammond, N.G.L. (2008). "The Emergence of the City-state from the Dark Age". Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. III Part 1 (2nd ed.). pp. 738–744.

- ^ The Copenhagen Poleis Project considered any mention of a polis in an ancient source to be solid evidence. Hansen states that they found over 11,000 instances of polis.[25]

- ^ Probably in the order of days or weeks, as the deal needed to be closed.

- ^ "Theseus ... abolished the councils and magistracies of the minor towns and brought all their inhabitants into union with what is now the city, establishing a single council and town hall, and compelled them, while continuing to occupy each his own lands as before, to use Athens as the sole capital.... And from his time even to this day the Athenians have celebrated at the public expense a festival called the Synoecia, ...."

- ^ There is no denying that Aristotle was an ardent exponent of slavery. He wrote (I.5) "from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule." The slaves nevertheless had some rights as members. At least at Athens they could not legally be murdered arbitrarily. Some slaves, such as the Scythian police, were given some power. Others were worked to death in the silver mines or forced into prostitution. Probably the great majority were allowed to earn their freedom to become trusted free retainers. In any case the assertion that slaves and women were not part of the polis is untrue.

- ^ I.3. The philosopher further distinguishes between slave (douloi) and free (eleutheroi), a distinction that plays a part in determining government: "a complete household consists of slaves and freemen."

- ^ Aristotle shows (I.3, I.4) that the oikia as a fixed settlement requires subsistence farming. He rejects hunting-gathering and any kind of nomadism as the economic basis for a polis. Trade is rejected as well, but an existing polis may engage in it as a supplement.

- ^ Aristotle had been a professor at the Academy, Plato's School, but disagreeing with the school he left it to found his own school in Macedonia with the backing of Phillip, who asked him to tutor his son, Alexander, not for long, as Alexander had to succeed Phillip. Aristotle opened a highly successful branch in Athens. His methods and resources (funded by the Macedonians) amounted to a university. Alexander sought his advice but the two disagreed on the treatment of conquered peoples. Aristotle advised to treat them as conquered peoples but Alexander was trying to fashion a new cross-cultural world state, cut short by his death. Without Macedonian backing Aristotle fell into disrepute and left Athens to die.

- ^ Aristotle always refers to Socrates, informal founder of the Academy, rather than Plato, the first legal master.

- ^ Many of the arguments advanced by Plato and Aristotle surface again in the epic modern struggles to establish or destroy what is most generally termed Marxism. Its founding father, Karl Marx, was much educated in philosophy, including classical, writing a doctor's thesis on a classical topic and at one point translating Latin classics for a living. The historical dialogue between Plato and Aristotle over the ideal polis will sound familiar to many moderns.

- ^ "Suppose a set of men inhabit the same place, in what circumstances are we to consider their city to be a single city?"

- ^ Today's meaning of politics is the cynical one, referring to popularly reprehensible behavior far removed from statesmanship.

- ^ Putting up your family was illegal but apparently it was done.

- ^ Solon's reforms are too large a topic to cover here. There are many interpretations, no certain answers.

- ^ The resemblance of these ideas to those expressed by the founders of modern nations is not accidental, as those founders were much influenced by classical thought.

Citations

- ^ Hansen 2004, pp. 70–72

- ^ Hansen 2008, pp. 261–265

- ^ The modern words can be found in any modern Greek dictionary; the ancient, any ancient Greek dictionary. Some instances are The Oxford Greek Dictionary, American Edition, for the modern, and Liddell and Scott's A Greek–English Lexicon for the ancient.

- ^ a b Hansen 2004, p. 4

- ^ "Word frequency information for πόλις". Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Flensted-Jensen, P.; Hansen, M.H.; Nielsen, E.H. (1993). "The Use of the Word Polis in Inscriptions". Further Studies in the Ancient Greek Polis. Stuttgart: Steiner. p. 161.

- ^ Hansen 2004, pp. 39–46

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "πόλις". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Sakellariou 1989, pp. 27–57, Chapter One: How Can the Polis Be Defined? The Debate

- ^ Davies, J.K. (1997). "The Origins of the Greek Polis". In Mitchell, L.G.; Rhodes, P.J. (eds.). The Development of the Polis in Archaic Greece. London: Routledge. p. 25.

regional trajectories of repopulation and development in the Dark Age and after clearly differed so sharply from each other in nature, scale and date that no one model for the 'rise of the polis' can possibly be valid.

- ^ Voegelin 1957

- ^ Voegelin 1957, p. 114

- ^ Sakellariou 1989, p. 19, Preface

- ^ Coulanges 1901, p. 16

- ^ Coulanges 1901, p. 168

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 130

- ^ Sakellariou 1989, p. 20

- ^ Fowler 1895, p. 8

- ^ a b Fowler 1895, p. 6

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 3 "the term polis is often used synonymously with the term 'city-state', and the concepts behind the two terms are often, but erroneously, thought to be co-extensive".

- ^ Peloponnesian War I.10

- ^ Michell, H. (1964). Sparta. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 64.

The second main division of the Lacedaemonioan state comprised the perioeci, 'dwellers in the outskirts'.... That these formed an integral part of the state, and that they were free, and, to some imperfectly defined degree, self-ruling but without the same political status as the Spartans, are all fairly clear facts....whether 'Dorians' or 'Achaeans'... are not so clear....

- ^ Graves, C.E. "Commentary on Thucydides: Book 4 Chapter VIII". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 87

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 12

- ^ a b Hansen 2004, p. 107

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 103

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 19

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 70

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "συνοικειόω". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "συνοικέω". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "συνοίκια". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "συνοικίζω". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "συνοικισμός". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 141

- ^ II.15.

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "συνοικιστήρ". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- .

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 75

- ^ "settlement patterns".

- ^ H. Rackham (1959). Aristotle Politics with an English Translation. London: Heinemann. p. xv.

- ^ Frank, Jill (2005). A Democracy of Distinction: Aristotle and the Work of Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "πολιτεία". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "πολίτης". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 80

- ^ Hansen 2004. The quote is Hansen's paraphrase.

- ^ Klosko, George (2020). "Oaths and Political Obligation in Ancient Greece" (PDF). History of Political Thought. XLI (1): 9.

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 95

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 131

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "πόλιτις". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Plato. "Laws 7.814c". Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Plato. "Laws 7.813e". Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Watkins 2009b dā-

- ^ Liddell; Scott. "δῆμος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 30

- ^ Hansen 2004, p. 76

- ^ Hansen 2004, pp. 95–97

Citation references

- Coulanges, Fustal de (1901). The Ancient City: Study of the Religion, Laws, and Institutions of Greece and Rome (PDF). Translated by Small, Willard (10th ed.). Boston: Lee and Shepard.

- Fowler, W.Warde (1895). The City-State of the Greeks and Romans: A Survey Introductory to the Study of Ancient History (Reprint ed.). London; New York: MacMillan and Co.

- Hansen, M.H. (2004). "Introduction". In Hansen, M.H.; Nielsen, T.H. (eds.). An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hansen, M.H. (2008). "An Update on the Shotgun Method". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 48.

- Sakellariou, Μ.Β. (1989). The Polis-State Definition And Origin (PDF). ΜΕΛΕΤΗΜΑΤΑ 4. Athens: Research Centre for Greek and Roman Antiquity National Hellenic Research Foundation.

- Voegelin, Eric (1957). The World of the Polis. Order and History, Volume Two. Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press.

- Watkins, Calvert (2009a). "Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans". The American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.). Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 2007–2015.

- Watkins, Calvert (2009b). "Appendix I: Indo-European Roots". The American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.). Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 2020–2055.