Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2011) |

| Tucson Presidio | |

|---|---|

| Tucson, Arizona, United States | |

The reconstructed northeastern bastion of the Tucson Presidio in 2009 | |

| Type | Army fortification |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Condition | tourist attraction |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1775–1783 |

| Built by | |

| In use | 1776–1886 |

| Materials | Adobe, mesquite, earth |

| Battles/wars | Apache–Mexico Wars

|

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | James H. Carleton |

| Occupants | |

Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón was a presidio (colonial Spanish fort) located within Tucson, Arizona, United States. The original fortress was built by Spanish soldiers during the 18th century and was the founding structure of what became the city of Tucson. After the American arrival in 1846, the original walls were dismantled, with the last section torn down in 1918. A reconstruction of the northeast corner of the fort was completed in 2007 following an archaeological excavation that located the fort's northeast tower.

History

Spanish Period

A

The following year, soldiers marched north from the Presidio at Tubac and began construction of the fort. Initially, it consisted of a scattering of buildings, some inside a wooden palisade. Mismanagement of the funds that were to be spent on adobe walls stalled their construction. A near disastrous attack by Apache raiders in June 1782 resulted in renewed efforts to complete the fort, which was accomplished in May 1783. The fort measured about 670 ft (200 m) to a side with square towers at the northeast and southwest corners. The main gate was on the center of the west wall, the presidial chapel was located along the east wall, the commandant's house was in the center, and the interior walls were lined with homes, stables, and warehouses. The massive adobe walls required constant maintenance, especially in times when attacks by Native Americans were anticipated, mostly from Apache. The fortress remained intact until the American arrival in 1856, two years after the Gadsden Treaty transferred southern Arizona to the United States. Afterward, it was rapidly dismantled, with the last standing portion torn down in 1918.

Tucson flourished under Spanish rule, but the population didn't exceed 500 until much later, when the

Fort Tubac was abandoned several times over 110 years due to repeated attacks at or near the fort. The garrisons remained relatively small, usually cavalry and some artillery. Lt. Juan de Olivas took command of Tucson after O'Connor from 1775 to 1777; Allande commanded the Tucson Presidio during four different attacks. He also commanded many of the advances into Apacheria and Seri country. Native warriors also contributed to the Tucson Presidio's defense several times during its history of fighting Apaches, sometimes because the natives allied with the Spanish were already long-time enemies with the Apache. The wars grew into sort of a stalemate; eventually the Spanish growth in the presidio topped off resulting in the small company size garrisons. The Spanish at any given point had fewer than 300 soldiers in all their presidios and settlements in the area. Presidio Santa Cruz de Terrenate was built along the San Pedro River southeast of Tucson in 1776, by 1780 it had already been abandoned due to Apache attacks. Presidio de San Bernardino was built just east of the present day Douglas, Arizona, in 1776 but was also abandoned in 1780. The contingents from most native groups which helped the Spanish were typically very small, about fifteen men but the Pimas contributed dozens of warriors to Captain Allande during the years who fought in most if not all of the frontier expeditions. Despite being outnumbered by the thousands, the Spanish held the majority of their settlements but could not decisively defeat the natives and stop them from raiding. Tucson became a Mexican town in 1821.

Mexican Period

When Mexico

By the time the

American Period

The United States Army took control of the Tucson Presidio in 1856 after eighty-one years in existence, and the city began to thrive once more. Famous

The great war against the Chiricahua began in 1860. After a raiding campaign into American territory against frontier settlements and the

Beginning just after the 1856 establishment of American Tucson, settlers in the southern New Mexico Territory began petitioning the government for separation. They hoped to establish a new territory in

With such a limited force of men, Hunter had orders to establish an alliance with the Native Americans in the region, particularly the Pimas. He also was directed to observe the advance of the

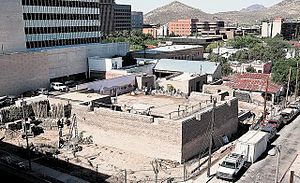

From the 1860s to 1890s Tucson would become a major stop for United States armies on campaigns to fight the Apache, hundreds of Tucson militia served in the expeditions. By the Mexican Revolution of 1910, the next war fought in southern Arizona, only one portion of the remaining four presidio walls still stood, the others were apparently buried or demolished for new development around the turn of the 20th century. The wall was three feet thick and a few feet tall. It stood in between two later American buildings and was finally destroyed in 1918. A pair of local women made a plaque which marked the location of the wall. In December 1954, a two-story boarding house was torn down to make way for a parking lot. A local business man convinced the University of Arizona to conduct an archaeological excavation. They located a 3-foot-thick (0.91 m) portion of the northeastern bastion. Attempts to have the area made into a park failed, and the parking lot was constructed.

The area was explored again by archaeologists between 2001 and 2006. Presidio-era features located there included the northeastern bastion, the east wall, soil mining pits, and trash-filled pits. Following the work, the northeastern corner of the fort was recreated as a museum, opening in 2007. Today, the Presidio San Agustin del Tucson Museum (www.TucsonPresidio.com) offers Living History Days, a variety of cultural events, and historic and cultural walking tours throughout Downtown Tucson. Other surviving portions of the Presidio wall are marked in the Old Pima County Courthouse courtyard and throughout Downtown Tucson.

Museum highlights

-

Presidio San Agustin del Tucson Museum

-

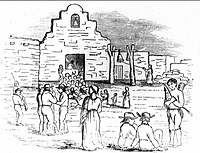

Presidio Tucson Museum, portion of a mural by Bill Singleton, 1972

-

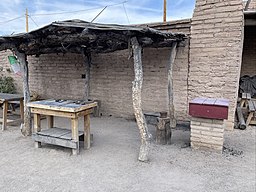

Presidio Tucson Museum, Married Men's Quarters

-

Presidio Tucson Museum, Single Men's Quarters

-

The Tucson presidio solder as depicted by Bill Singleton in his mural, 1972. They dressed in heavy seven-layered deerskin armor and carried a shield of three layers of half-tanned rawhide. Their primary weapon was a nine-foot long lance.

-

The presidio Tucson Blacksmith Shop. The Tucson Ring Meteorite was used for years as an anvil in the presidio blacksmith shop. The meteorite is now on display in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C.

-

In 1954, archaeologists from the University of Arizona discovered a Hohokam pit house underlying the Tucson Presidio.

See also

References

- ^ "25 Things You Should Know About Tucson". mentalfloss.com. 17 August 2017.

- ISBN 978-0976017301– via Google Books.

Sources

- Cooper, Evelyn S., (1995), Tucson in Focus: The Buehman Studio, Arizona Historical Society, Tucson. ISBN 0-910037-35-3.

- Tompkins, Walter A., Santa Barbara History Makers, McNally & Loftin, 1983, p. 105. ISBN 0-87461-059-1

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe, 1888, History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530–1888. The History Company, San Francisco.

- Spanish Colonial Tucson, ISBN 0-8165-0546-2.

- Drachman, Roy P., 1999, From Cowtown to Desert Metropolis: Ninety Years of Arizona Memories, Whitewing Press, San Francisco. ISBN 1-888965-02-9