Russian tea culture

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2024) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (January 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

History

There is a wide-spread legend claiming that Russian people first came in contact with tea in 1567, when the Cossack Atamans Petrov and Yalyshev visited China.[3] This was popularized in the popular and widely-read Tales of the Russian People by Ivan Sakharov, but modern historians generally consider the manuscript to be fake, and the embassy of Petrov and Yalyshev itself is fictional.[4]

Tea culture accelerated in 1638 when a

Between the Treaty of Nerchinsk and the

The word “tea” in Russian was first encountered in medical texts of the mid-17th century, for example, in “Materials for the history of medicine in Russia”: “herbs for tea; ramon color (?) - 3 handfuls each” (issue 2, No. 365, 1665, 291), “boiled chage (probably chaje or the same, but through the Greek “scale”) to a leaf of Khinskiy (typo: khanskiy)”.[11]

The peak year for the

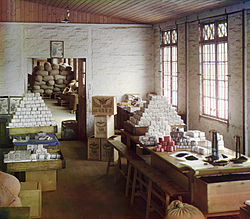

By the late 19th century, Wissotzky Tea had become the largest tea firm in the Russian Empire. By the early 20th century, Wissotzky was the largest tea manufacturer in the world.[15]

By the end of the 18th century, tea prices had moderately declined. The first local tea plant was set in Nikitsk

Varieties

Traditionally, black tea is the most common tea in Russia, but green tea is becoming popular too.

Traditional tea in Russia includes the traditional type known as

It is common, particularly in the countryside, to add herbs and berries to the leaves, such as mint, melissa, blackcurrant leaves, St. John's wort, raspberries, or sweet briar hips. Sometimes, fireweed is used to replace tea leaves altogether.

Brewing and serving

A notable feature of Russian tea culture is the two-step brewing process. First, tea concentrate called zavarka (

; using the personal teaspoon to add them to the tea rather than the one in the bowl is considered impolite.Zavarka can be brewed from the same leaves up to three times, but this is generally recognized to dilute and thus spoil the taste, unless it is green tea being brewed.

Tea sachets are widely popular in Russia, but less so than the world average, taking up about 50% of the Russian market compared to the 90% worldwide. While the simplicity of brewing such tea makes it popular for quick tea breaks, it is generally thought to be inferior to loose leaf tea brewed into zavarka both in the quality of the leaves available in mass-market brands and the quality of extraction during the brewing process itself.

A samovar was widely used to boil water for brewing until mid-20th century, when the spread of gas stoves in then-newly mass-constructed apartment buildings largely saw it replaced with kettles. From the 1990s, electric kettles have become the norm.

Drinking tea is an integral part of every Russian meal; it is served with dessert. Pastries, confectioneries, and varenye are rarely consumed while not accompanied by tea, and vice versa, such sweet products are commonly categorized as something "к чаю" - "to add to the tea". A tea party is also universally a part of a festive meal: meat and other savory food is then served as the first course, and tea serves as the second, normally accompanied by a large cake. There is no formal ceremony to drinking tea, on the contrary, tea-drinking is considered to be the best time for small talk. The end of drinking tea then also signals the end of the meal.

Conversely, a tea time can also be had separately from a meal. Tea parties can be formal occasions on their own, and it is not uncommon for Russians to be sipping tea throughout the day. Furthermore, tea is offered as a form of courtesy to guests, even on short visits, especially when it is cold outside. Office culture in particular includes not just tea breaks, but tea served during lengthy meetings, and offered wherever a visitor has to wait any meaningful amount of time. On such occasions, tea is usually brewed in satchels, and accompanied by nothing but sugar and maybe a single pastry variety.

On formal occasions, tea is enjoyed from porcelain or faïence teacups with matching saucers; such teacups are rarely larger than 200 to 250 ml. While it is not a hard etiquette requirement, it is considered good taste for teacups to come from a single set for everyone at the table. Thus, many Russian families have a tea set set aside especially for festive and formal occasions. Russian porcelain factories offer a wide range of such tea sets, the Imperial Porcelain Factory cobalt blue net design with 22 karat gold in particular considered something of a household name.

In more casual situations, tea can be drunk from any cups or mugs, their size reaching up to half a liter or even more. If the beverage in the cup is excessively hot, it is considered permissible, - but not polite, - to sip it from the saucer.

Tea culture

According to William Pokhlyobkin, tea in Russia was not regarded as a self-dependent beverage; thus, even the affluent classes adorned it with a jam, syrup, cakes, cookies, candies, lemon and other sweets. This is similar to the archaic idiom "чай да сахар" (tea and sugar, translit. chay da sakhar). The Russian language utilizes some colloquialisms pertaining to tea consumption, including "чайку-с?" ("some tea?" in an archaic manner, translit. chayku s), used by the pre-Revolutionary attendants. The others are "гонять чаи" (chase the teas, i.e. drinking the tea for overly prolonged periods; translit. gonyat' chaii) and "побаловаться чайком" (indulging in tea, translit. pobalovat'sya chaykom). Tea was made a significant element of cultural life by the literati of the Karamzinian circle.[17] By the mid-19th century tea had won over the town class, the merchants and the petty bourgeoisie.[17] This is reflected in the dramas of Alexander Ostrovsky. Since Ostrovsky's time, the duration of time and the amount of tea consumed have appreciated.

In the Soviet period, tea-drinking was extremely popular in the daily life of office workers (female secretaries, laboratory assistants, etc.). Tea brands of the time were nicknamed "the brooms" (Georgian) and "the tea with an elephant" (Indian).[17] Tea was an immutable element of kitchen life among the intelligentsia in 1960s-'70s.[17]

In pre-Revolutionary Russia there was a joke "что после чаю следует?" ('what follows after tea?', translit. chto poslye chayu slyeduyet) with the correct answer being "the

In the 19th century, Russians drank their tea with a cube of sugar (from sugarloaf) held between their teeth.[18] The tradition still exists today.[19]

Tea is very popular in Russian prisons. Traditional mind-altering substances such as alcohol are typically prohibited, and very high concentrations, called chifir are used as a substitute.[20]

Russians who are not ethnically Russian have their own tea cultures. Kalmyk tea, for instance, most resembles Mongolian suutei tsai, and includes brewing loose leaves with milk (twice larger amount than that of water), salt, bay leaf, nutmeg, cloves, or butter, to be enjoyed with flatbread. Water substituted with milk allows the beverage to more easily be produced in the arid terrain of Kalmykia.

"Russian Tea" in other countries

United States

There is a beverage called "Russian Tea" which likely originated in America. This drink is especially popular in the

The drink is served hot and often an evening or after-meal beverage. However, iced versions are sometimes offered with meals at cafés.

Despite the name, "Russian Tea" probably has no link to its namesake. References to "Russian Tea" and instructions have been found in American newspapers and cookbooks dating as early as the 1880s.[21]

Japan

In Japan, the term "Russian tea" is used to refer specifically to the act of having black tea with a spoonful of jam, whether added into the cup or placed on the tongue before drinking. The typical choice is strawberry jam, but not exclusively so.[22][23]

See also

Notes

- ISBN 0-313-32773-4.

- PMID 16044841.

- ^ "Russian Tea History". www.apollotea.com. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- ^ Filyushkin, Alexander (October 2004). "Журнал "Родина": Дойти до Поднебесной". Rodina Magazine. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- ^ a b c Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Советская энциклопедия. 1978. pp. vol. 29, p. 11.

- ^ Jeremiah Curtin, A Journey to Southern Siberia, 1909, Chapter one

- ^ Basil Dymytryshyn, Russia's Conquest of Siberia: A Documentary Record, 1985, volume one, document 48 (he was an envoy that year, but the tea may have been given on a later visit to the Khan)

- ^ DeLaine, Linda. "Tea Time in Russia". Russian Life. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ "Tea Time in Russia: Russian Life". Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ISBN 1-883914-18-3.

- ^ N. Novombergskij, N (1665). Materials for the History of Medicine in Russia.

- ISBN 0-415-92722-6.

- ISBN 7-5085-0380-5.

- ISBN 978-1-84541-057-5.

- ^ Merchants to Multinationals: British Trading Companies in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Geoffrey Jones, Oxford University Press, 2000

- ISBN 0-670-88401-4.

- ^ ISSN 0130-1640

- ISBN 0-8118-3053-5.

- ^ "САХАР ВПРИКУСКУ". САХАР ВПРИКУСКУ | ТВЕРДЫЙ САХАР №1 В РОССИИ.

- ^ "Russian Tea HOWTO" (PDF). 2002-04-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-27. Retrieved 2008-04-26.

- ^ a b "Russian Tea: America's choice in outer space under a Soviet name". Yesterdish: Rescuing America's Lost Recipes. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ "ロシアのお茶文化|世界のお茶専門店 ルピシア ~紅茶・緑茶・烏龍茶・ハーブ~". www.lupicia.com. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- ^ "ロシア人はおもてなしの達人<後編> ロシアンティーの本当の飲み方は?:朝日新聞GLOBE+". 朝日新聞GLOBE+ (in Japanese). 9 April 2020. Retrieved 2021-10-14.