SMS Stettin

SMS Stettin in 1912

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Stettin |

| Namesake | Stettin |

| Builder | AG Vulcan, Stettin |

| Laid down | 1906 |

| Launched | 7 March 1907 |

| Commissioned | 29 October 1907 |

| Stricken | 5 November 1919 |

| Fate | Ceded to Britain 1920, scrapped in 1921–1923 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Königsberg-class light cruiser |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 115.3 m (378 ft) |

| Beam | 13.2 m (43 ft) |

| Draft | 5.29 m (17.4 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 24 knots (44.4 km/h; 27.6 mph) |

| Range | 5,750 nautical miles (10,650 km; 6,620 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Stettin ("His Majesty's Ship Stettin")

In 1912, Stettin joined the battlecruiser Moltke and cruiser Bremen for a goodwill visit to the United States. After the outbreak of World War I, Stettin served in the reconnaissance forces of the German fleet. She saw heavy service for the first three years of the war, including at the Battle of Heligoland Bight in August 1914 and the Battle of Jutland in May – June 1916, along with other smaller operations in the North and Baltic Seas. In 1917, she was withdrawn from frontline service and used as a training ship until the end of the war. In the aftermath of Germany's defeat, Stettin was surrendered to the Allies and broke up for scrap in 1921–1923.

Design

The Königsberg-class ships were designed to serve both as fleet scouts in home waters and in

Stettin was 115.3 meters (378 ft)

The ship was armed with a

Service history

Stettin was ordered under the contract name "

After her commissioning, Stettin served with the High Seas Fleet in German waters.[8] In early 1912, Stettin was assigned to a goodwill cruise to the United States, along with the battlecruiser Moltke, the only German capital ship to ever visit the US, and the light cruiser Bremen. On 11 May 1912 the ships left Kiel and arrived off Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 30 May. There, they met the US Atlantic Fleet and were greeted by then-President William Howard Taft aboard the presidential yacht USS Mayflower. After touring the East Coast for two weeks, they returned to Kiel on 24 June.[9][10]

Actions in the North Sea

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Stettin was serving in the North Sea with the High Seas Fleet. On 6 August, she and the cruiser Hamburg escorted a flotilla of U-boats into the North Sea in an attempt to draw out the British fleet, which could then be attacked by the U-boats. The force returned to port on 11 August, without having encountered any British warships.[11] Some two weeks later, on 28 August, Stettin was involved in the Battle of Heligoland Bight. At the start of the engagement, Stettin, Frauenlob, and Hela stood in support of the line of torpedo boats patrolling the Heligoland Bight; Stettin was at anchor to the northeast of Heligoland island, and the other two ships were on either side. The German screen was under the command of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper, the commander of reconnaissance forces for the High Seas Fleet.[12]

When the British first attacked the German torpedo boats, Hipper immediately dispatched Stettin and Frauenlob, and several other cruisers that were in distant support, to come to their aid. At 08:32, Stettin received the report of German torpedo boats in contact with the British, and immediately weighed anchor and steamed off to support them. Twenty-six minutes later, she encountered the British destroyers and opened fire, at a range of 8.5 km (5.3 mi). The attack forced the British ships to break off and turn back west. During the engagement, lookouts aboard Stettin spotted a British cruiser in the distance, but it did not join the battle. By 9:10, the British had withdrawn out of range, and Stettin fell back to get steam in all of her boilers. During this portion of the battle, the ship was hit once, on the starboard No. 4 gun, which killed two men and badly injured another. Her intervention prevented the British from sinking the torpedo boats V1 and S13.[13]

By 10:00, Stettin had steam in all of her boilers, and was capable of her top speed. She therefore returned to the battle, and at 10:06, she encountered eight British destroyers and immediately attacked them, opening fire at 10:08. Several hits were observed in the British formation, which dispersed and fled. By 10:13, the visibility had decreased, and Stettin could no longer see the fleeing destroyers, and so broke off the chase. The ship had been hit several times in return, without causing significant damage, but killing another two and wounding another four men. At around 13:40, Stettin reached with the cruiser Ariadne, which was just coming under attack from several British battlecruisers. Stettin's crew could see the large muzzle flashes in the haze, which after having disabled Ariadne, turned on Stettin at 14:05. The haze saved the ship, which was able to escape after ten salvos missed her. At 14:20, she encountered Danzig. The German battlecruisers Von der Tann and Moltke reached the scene by 15:25, by which time the British had already disengaged and withdrawn. Hipper, in Seydlitz, followed closely behind, and ordered the light cruisers to fall back on his ships. After conducting a short reconnaissance further west, the Germans returned to port, arriving in Wilhelmshaven by 21:30.[14]

On 15 December, the battlecruisers of

Operations in the Baltic

On 7 May 1915, IV Scouting Group, which by then consisted of Stettin, Stuttgart, München, and Danzig, and twenty-one torpedo boats was sent into the Baltic Sea to support a major operation against Russian positions at Libau. The operation was commanded by Rear Admiral Hopman, the commander of the reconnaissance forces in the Baltic. IV Scouting Group was tasked with screening to the north to prevent any Russian naval forces from moving out of the Gulf of Finland undetected, while several armored cruisers and other warships bombarded the port. The Russians did attempt to intervene with a force of four cruisers: Admiral Makarov, Bayan, Oleg, and Bogatyr. The Russian ships briefly engaged München, but both sides were unsure of the others' strength, and so both disengaged. Shortly after the bombardment, Libau was captured by the advancing German army, and Stettin and the rest of IV Scouting Group were recalled to the High Seas Fleet.[17]

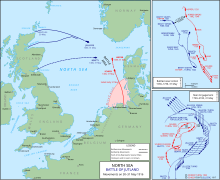

Battle of Jutland

In May 1916, the German fleet commander, Admiral Reinhard Scheer, planned a major operation to cut off and destroy an isolated squadron of the British fleet. The operation resulted in the battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916.[18] During the battle, Stettin served as the flagship of Commodore Ludwig von Reuter, the commander of IV Scouting Group.[19] IV Scouting Group was tasked with screening for the main German battlefleet. As the German fleet approached the scene of the unfolding engagement between the British and German battlecruiser squadrons, Stettin steamed ahead of the leading German battleship, König, with the rest of the Group dispersed to screen for submarines. Stettin and IV Scouting Group were not heavily engaged during the early phases of the battle, but around 21:30, they encountered the British cruiser HMS Falmouth. Stettin and München briefly fired on the British ship, but poor visibility forced the ships to cease fire. Reuter turned his ships 90 degrees away and disappeared in the haze.[20]

During the withdrawal from the battle on the night of 31 May at around 23:30, the battlecruisers Moltke and Seydlitz passed ahead of Stettin too closely, forcing her to slow down. The rest of IV Scouting Group did not notice the reduction in speed, and so the ships became disorganized. Shortly thereafter, the British 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron came upon the German cruisers, which were joined by Hamburg, Elbing, and Rostock. A ferocious firefight at very close range ensued; Stettin was hit twice early in the engagement and was set on fire. A shell fragment punctured the steam pipe for the ship's siren, and the escaping steam impaired visibility and forced the ship to abandon an attempt to launch torpedoes. In the melee, HMS Southampton was hit by approximately eighteen 10.5 cm shells, including some from Stettin. In the meantime, the German cruiser Frauenlob was set on fire and sunk; as the German cruisers turned to avoid colliding with the sinking wreck, IV Scouting Group became dispersed. Only München remained with Stettin. The two ships accidentally attacked the German destroyers G11, V1, and V3 at 23:55.[21]

By 04:00 on 1 June, the German fleet had evaded the British fleet and reached

Fate

In 1917, Stettin was withdrawn from front line service and used as a

Notes

Footnotes

- Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- ^ German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)".

Citations

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, pp. 142, 157.

- ^ Nottelmann, pp. 110–114.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 188.

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 104.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, pp. 140, 157.

- ^ Gröner, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 187–188.

- ^ a b c Gröner, p. 105.

- ^ Staff 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Hadley & Sarty, p. 66.

- ^ Scheer, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Staff 2011, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Staff 2011, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Staff 2011, pp. 10–11, 21–22, 26.

- ^ Scheer, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 191–193.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 61.

- ^ Scheer, p. 138.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 35, 251–252.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 276, 280–284, 390.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 341, 360.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 157.

- ^ Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Article 185

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hadley, Michael L.; Sarty, Roger (1995). Tin-pots and Pirate Ships: Canadian Naval Forces and German Sea Raiders, 1880–1918. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-304-35848-7.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 7. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. OCLC 310653560.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2020). "The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

- OCLC 2765294. Archived from the originalon 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- Staff, Gary (2011). Battle on the Seven Seas. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84884-182-6.

- Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-009-3.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 0-304-35848-7.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.

- ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.