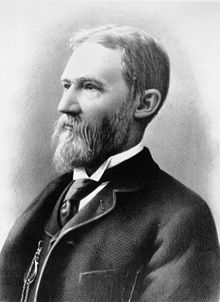

Samuel Griffith

Queensland Legislative Assembly | |

|---|---|

| In office 13 June 1888 – 29 April 1893 | |

| Preceded by | New seat |

| Succeeded by | John James Kingsbury |

| Constituency | Brisbane North |

| In office 15 November 1878 – 13 June 1888 | |

| Preceded by | New seat |

| Succeeded by | Abolished |

| Constituency | North Brisbane |

| In office 25 November 1873 – 14 November 1878 | |

| Preceded by | New seat |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Grimes |

| Constituency | Oxley |

| In office 3 April 1872 – 25 November 1873 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Travers Atkin |

| Succeeded by | William Fryar |

| Constituency | East Moreton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 June 1845 Merthyr Tydfil, Glamorgan, Wales |

| Died | 9 August 1920 (aged 75) Brisbane, Queensland, Australia |

| Resting place | Toowong Cemetery |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse |

Julia Thomson (m. 1870) |

| Relations | Mary Harriett Griffith (sister) |

| Alma mater | University of Sydney |

| Occupation | Politician, judge |

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith

Griffith was born in

In 1893, Griffith retired from politics to head the Supreme Court of Queensland. He was frequently asked to assist in drafting legislation, and the Queensland criminal code – the first in Australia – was mostly his creation. Griffith was an ardent federationist, and with Andrew Inglis Clark wrote the draft constitution that was presented to the 1891 constitutional convention. Many of his contributions were preserved in the final constitution enacted in 1900. Griffith was involved in the drafting of the federal Judiciary Act 1903, which established the High Court of Australia, and was subsequently nominated by Alfred Deakin to become the inaugural Chief Justice. He presided over a number of constitutional cases, though some of his interpretations were rejected by later courts. He was also called on to advise governors-general during political instability. Griffith University and the Canberra suburb of Griffith are named in his honour.

Early life

Griffith was born in

In 1865, he gained the

On his return to Brisbane, Griffith studied law and was articled to

In 1870, Griffith returned to Sydney to complete a Master of Arts.[1] In the same year, he married Julia Janet Thomson.[1]

Political career

In 1872 Griffith was elected to the

Griffith had had a distinguished career in Queensland politics. Included in the legislation for which he was responsible were an offenders' probation act, and an act which codified the law relating to the duties and powers of justices of the peace. He also succeeded in passing an eight hours bill through the assembly which was, however, thrown out by the Queensland Legislative Council.[2]

Griffith became Premier in November 1883

Griffith held the office of premier until 1888, and was made a

But in 1890 Griffith suddenly betrayed his radical friends and became Premier again at the head of an unlikely alliance with McIlwraith, the so-called "

Chief Justice of Queensland

On 13 March 1893, the Governor accepted Griffith's resignation from Vice-President and Member of the Executive Council and Chief Secretary and Attorney General and appointed Griffith to Chief Justice of the

During his term as Chief Justice Griffith drafted Queensland's Criminal Code,[11] a successful codification of the entire English criminal law, which was adopted in 1899, and later in Western Australia, Papua New Guinea, substantially in Tasmania, and other imperial territories including Nigeria.[12] At May 2006 the Queensland Criminal Code remains largely unchanged.

Chief Justice of Australia

When the federal parliament passed the

Griffith was the first of two justices of the High Court of Australia to have previously served in the

Royal Commissions

In January 1918, Griffith was appointed by Prime Minister

Later writers have seen Griffith's involvement in the Royal Commission as inadvisable, as the findings were able to be used for political purposes and thus could be seen to have breached the separation of powers. It is the most recent occasion on which a sitting High Court judge has chaired a Royal Commission; Griffith had also authorised the first, which was conducted by George Rich in 1915 and also concerned military issues. However, in July 1918 he rejected another request from Hughes for a High Court judge to conduct a Royal Commission, on the grounds that it would "associate the High Court with political action".[15]

Retirement and death

Griffith retired from the Court in 1919 and died at his home in Brisbane on 9 August 1920.[1] He is buried in Toowong Cemetery, Brisbane,[1] together with his wife, Julia, and their son, Llewellyn. Cemetery records indicate that their plot adjoins that of Griffith's dear friend Charles Mein (1841–1890) (barrister, politician and judge), the pair having met during their undergraduate studies at the University of Sydney.[16]

Honours

Griffith is commemorated by the naming of

In July 2016 Griffith was inducted in to the City of Maitland Hall of Fame.

Although demolished in 1963, his home Merthyr, named after his birthplace, gives its name to the neighbourhood of

See also

- List of Judges of the High Court of Australia

- List of Judges of the Supreme Court of Queensland

Notes

- ^ ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Mennell, Philip (1892). . The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. London: Hutchinson & Co – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Joyce, R. B., "Griffith, Sir Samuel Walker (1845–1920)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 14 June 2023

- ^ "Sir Samuel Griffith GCMG QC". Supreme Court Library Queensland. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ a b

Roberts, Beryl (1991). Stories of the Southside. Archerfield, Queensland: Aussie Books. p. 6. ISBN 0-947336-01-X.

- ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ "Portraits of Chief Justices and the first bench". High Court of Australia. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9780702211270.

- ^ Queensland Government Gazette Extraordinary Vol. LVIII No.63 Monday 13 March 1893 p777

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889-1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021, p.250.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company. p. 321.

- ^ Bruce McPherson, Supreme Court of Queensland, Butterworths, 1984

- ^ "Documenting a Democracy Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth)". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Donald Markwell, "Griffith, Barton and the early governor-generals: aspects of Australia's constitutional development", Public Law Review, 1999.

- ^ a b Fiona Wheler (30 November 2011). "'Anomalous Occurrences in Unusual Circumstances'? Towards a History of Extra-Judicial Activity by High Court Justices" (PDF). High Court of Australia Public Lectures. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 4 October 2017.)

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ "Drive renamed". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 5 January 1951. p. 3. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ "Santa Barbara, New Farm". Your Brisbane: Past and Present. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

Further reading

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Griffith, Samuel Walker". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- Joyce, Roger B: Samuel Walker Griffith, St Lucia (University of Queensland Press), 1984.

- Joyce R.B. & Murphy, D.J.(Ed.): Queensland Political Portraits, St Lucia (University of Queensland Press), 1978.

External links

- Queensland Criminal Code

- The Australian Constitution

- Griffith University, Brisbane

- Samuel Griffith Society

- Griffith, Samuel Walker — Brisbane City Council Grave Location Search