Satsuma Domain

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2009) |

| Kagoshima Domain (1869–1871)鹿児島藩 Satsuma Domain (1602–1869)薩摩藩 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain of Japan | |||||||||||||

| 1602–1871 | |||||||||||||

Former site of Kagoshima Castle in Kagoshima | |||||||||||||

Daimyō | | ||||||||||||

• 1602–1638 | Shimazu Iehisa (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1858–1871 | Shimazu Tadayoshi (last) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Edo period | ||||||||||||

• Established | 1602 | ||||||||||||

| 1871 | |||||||||||||

| Contained within | |||||||||||||

| • Province | Satsuma, Ōsumi, Hyūga | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Whole: Oita Prefecture | ||||||||||||

The Satsuma Domain (薩摩藩, Satsuma-han Ryukyuan: Sachima-han), briefly known as the Kagoshima Domain (鹿児島藩, Kagoshima-han), was a domain (han) of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan during the Edo period from 1602 to 1871.

The Satsuma Domain was based at

The Satsuma Domain was one of the most powerful and prominent of Japan's domains during the Edo period, conquering the

History

The

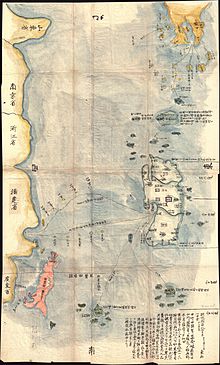

Ryukyu

Since the mid-15th century, Satsuma fought with the

For the remainder of the Edo period, Satsuma influenced their politics and dominated their trading policies to take advantage of Ryukyu's

In 1871, however, Emperor Meiji abolished the han system, and the following year informed King Shō Tai that he was designated "Domain Head of Ryukyu Domain", transferring Satsuma's authority over the country to Tokyo.

Edo period

Though not the wealthiest han in terms of

The Shimazu exercised their influence to exact from the shogunate a number of special exceptions. Satsuma was granted an exception to the shogunate's limit of one castle per domain, a policy which was meant to restrict the military strength of the domains; the Shimazu then formed sub-fiefs within their domain, and doled out castles to their vassals, administering the domain in a manner not unlike a mini-shogunate. They also received special exceptions from the shogunate in regard to the policy of sankin-kōtai, another policy meant to restrict the wealth and power of the daimyō. Under this policy, every feudal lord was mandated to travel to Edo at least once a year, and to spend some portion of the year there, away from his domain and his power base. The Shimazu were granted permission to make this journey only once every two years. These exceptions thus allowed Satsuma to gain even more power and wealth relative to the majority of other domains.

Though arguably opposed to the shogunate, Satsuma was perhaps one of the strictest domains in enforcing particular policies. Christian missionaries were seen as a serious threat to the power of the daimyō, and the peace and order of the domain; the shogunal ban on Christianity was enforced more strictly and brutally in Satsuma, perhaps, than anywhere else in the archipelago. The ban on smuggling, perhaps unsurprisingly, was not so strictly enforced, as the domain gained significantly from trade performed along its shores, some ways away from Nagasaki, where the shogunate monopolized commerce. In the 1830s, Satsuma used its illegal Okinawa trade to rebuild its finances under Zusho Hirosato.

Bakumatsu

The Satsuma daimyō of the 1850s, Shimazu Nariakira, was very interested in Western thought and technology, and sought to open the country. At the time, contacts with Westerners increased dramatically, particularly for Satsuma, as Western ships frequently landed in the Ryukyus and sought not only trade, but formal diplomatic relations. To increase his influence in the shogunate, Nariakira engineered a marriage between Shōgun Tokugawa Iesada and his adopted daughter, Atsu-hime (later Tenshō-in).

In 1854, the first year of Iesada's reign, Commodore Perry landed in Japan and forced an end to the isolation policy of the shogunate. However, the treaties signed between Japan and the western powers, particularly the Harris Treaty of 1858, put Japan at a serious disadvantage. In the same year, both Iesada and Nariakira died. Nariakira named his nephew, Shimazu Tadayoshi, as his successor. As Tadayoshi was still a child, his father, Shimazu Hisamitsu, effectively held the power in Satsuma.

Hisamitsu followed a policy of as the major supporter.

In 1862, in the Namamugi Incident an Englishman was killed by retainers of Satsuma, leading to the bombardment of Kagoshima by the Royal Navy the following year. Even though Satsuma was able to withstand the attack, this event showed how necessary it was for Japan to import western technology and reform its military.

Meanwhile, the focus of Japanese politics shifted to Kyoto, where the major struggles of the time occurred. The shogunate entrusted Satsuma and

When the shogunate decided to finally defeat Chōshū in a Second Chōshū expedition the next year, Satsuma, under the lead of Saigo Takamori and Ōkubo Toshimichi, decided to switch sides. The Satchō Alliance between Satsuma and Chōshū was brokered by Sakamoto Ryōma from Tosa.

This second expedition ended in a disaster for the shogunate. It was defeated on the battlefield, and Shōgun Iemochi died of illness in Osaka Castle. The next shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, brokered a cease fire.

Despite attempts by the new shōgun to reform the government, he was unable to contain the growing movement to overthrow the shogunate led by Satsuma and Chōshū. Even after he stepped down as shōgun and agreed to return the power to the Imperial court, the two sides finally clashed in the Battle of Toba–Fushimi 1868. The shōgun, defeated, escaped to Edo. Saigo Takamori then led his troops to Edo, where Tenshō-in was instrumental in the bloodless surrender of Edo castle. The Boshin War continued until the last of the shogunate forces were defeated in 1869.

Meiji period

The

However, the beginning of the period was marked by growing discontent of the former samurai class, which erupted in the Satsuma Rebellion under Saigo Takamori in 1877.

List of daimyōs

The hereditary

| Name | Tenure | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shimazu Iehisa (島津家久) |

1602–1638 |

| 2 | Shimazu Mitsuhisa (島津光久) | 1638–1687 |

| 3 | Shimazu Tsunataka (島津綱貴) | 1687–1704 |

| 4 | Shimazu Yoshitaka (島津吉貴) | 1704–1721 |

| 5 | Shimazu Tsugutoyo (島津継豊) | 1721–1746 |

| 6 | Shimazu Munenobu (島津宗信) | 1746–1749 |

| 7 | Shimazu Shigetoshi (島津重年) | 1749–1755 |

| 8 | Shimazu Shigehide (島津重豪) | 1755–1787 |

| 9 | Shimazu Narinobu (島津斉宣) | 1787–1809 |

| 10 | Shimazu Narioki (島津斉興) | 1809–1851 |

| 11 | Shimazu Nariakira (島津斉彬) | 1851–1858 |

| 12 | Shimazu Tadayoshi (島津忠義) | 1858–1871 |

Other major figures from Satsuma

- Saigō Takamori

- Ōkubo Toshimichi

- Komatsu Tatewaki

- Tenshōin, official wife of shogun Tokugawa Iesada

Meiji period statesmen and diplomats

- Kuroda Kiyotaka, 2nd Prime Minister of Japan

- Matsukata Masayoshi, 4th and 6th Prime Minister

- Yamamoto Gonnohyōe. 22nd Prime Minister

- Mori Arinori

- Makino Nobuaki

- Nishi Tokujirō

- Terashima Munenori

- Saigō Tsugumichi, younger brother of Saigo Takamori

- Mishima Michitsune

- Narahara Shigeru

- Tōgō Heihachirō

- Saneyoshi Yasuzumi

- Kawamura Sumiyoshi

- Kataoka Shichirō

- Shibayama Yahachi

- Takeshita Isamu

- Nire Kagenori

- Kamimura Hikonojō

- Ijuin Gorō

- Itō Sukeyuki

- Inoue Yoshika

- Kabayama Sukenori, 1st Governor-General of Taiwan

- Samejima Kazunori, president of the Naval War College, Admiral and baron.

- Uehara Yūsaku

- Nozu Michitsura, field marshal

- Ōyama Iwao, field marshal

- Kawamura Kageaki, field marshal

- Kawakami Soroku

- Takashima Tomonosuke

Artists

- Kuroda Seiki, yōga painter

Entrepreneurs

See also

- Abolition of the han system

- History of Kagoshima Prefecture

- List of han

- Museum of the Meiji Restoration

Explanatory notes

- ^ Flag used by the Satsuma army during the Boshin War from 1868 to 1869.

References

- ^ Mass, Jeffrey P. and William B. Hauser. (1987). The Bakufu in Japanese History, p. 150.

- ^ Elison, George and Bardwell L. Smith (1987). Warlords, Artists, & Commoners: Japan in the Sixteenth Century, p. 18.

- ^ Totman, Conrad. (1993). Early Modern Japan, p. 119.

Further reading

- Sagers, John H. Origins of Japanese Wealth and Power: Reconciling Confucianism and Capitalism, 1830–1885. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Sakai, Robert (May 1957). "Feudal Society and Modern Leadership in Satsuma-han". Journal of Asian Studies. Vol. 16, no. 3. pp. 365–376. JSTOR 2941231.

- Sakai, Robert (1968). "The Consolidation of Power in Satsuma-han". In Studies in the Institutional History of Early Modern Japan. (Marius Janseneds.) Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sakai, Robert, et al. (1975). The Status System and Social Organization of Satsuma. Tokyo: Tokyo University Press.

External links

Media related to Satsuma Domain at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Satsuma Domain at Wikimedia Commons