Stapleton Cotton, 1st Viscount Combermere

George III | |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | John Foster Alleyne (acting) |

| Succeeded by | John Brathwaite Skeete (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 November 1773 Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order Knight Companion of the Order of the Star of India |

| Military service | |

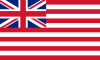

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1790–1830 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Commands | 25th Light Dragoons 16th Light Dragoons Commander-in-Chief, Ireland Commander-in-Chief, India |

| Battles/wars | French Revolutionary Wars Fourth Anglo-Mysore War Peninsular War |

Career

1790–1805

Cotton was born at Lleweni Hall in Denbighshire,[1] the second surviving son of Sir Robert Salusbury Cotton, 5th Baronet and Frances Cotton (née Stapleton). When he was eight, Cotton was sent to board at the grammar school in Audlem some 8 miles (13 km) from the family's estate at Combermere Abbey, where he was tutored by the headmaster, the Reverend William Salmon, who was also chaplain of the private Cotton chapel outside the estate gates.[2] A quick, lively boy, he was known by his family as 'Young Rapid,' and was continually in scrapes.[3] After three years in Audlem, he continued his education at Westminster School where he joined the fourth form under Dr. Dodd and his contemporaries included future soldiers Jack Byng, Robert Wilson and the poet Robert Southey.[2] He was then sent to Norwood House, a private military academy in Bayswater, which was run by a Shropshire militiaman, Major Reynolds, an acquaintance of his father's. On 26 February 1790, Cotton's father obtained for him a second-lieutenancy, without purchase, in the 23rd Regiment of Foot or Royal Welch Fusiliers, which he joined in Dublin in 1791.[4][5] He was promoted to lieutenant in the 77th Regiment of Foot on 9 April 1791[6] and, having transferred back to the 23rd Regiment of Foot on 13 April 1791,[7] he was promoted to captain in the 6th Dragoon Guards on 28 February 1793.[8] He served with his regiment at the Siege of Dunkirk in August 1793 and at the Battle of Beaumont in April 1794 under the Duke of York during the Flanders Campaign.[9] He became a major in the 59th Regiment of Foot on 28 April 1794 and commanding officer of the 25th Light Dragoons (subsequently 22nd) with the rank of lieutenant colonel on 27 September 1794.[10]

In 1796 Cotton went with his regiment to India. En route he took part in operations in Cape Colony (July to August 1796), and on arrival was present at the Siege of Seringapatam in May 1799 during the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War,[9] where he first met Colonel Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington.[11] He became commanding officer of the 16th Light Dragoons, then based in Brighton, on 18 February 1800.[12] Promoted to colonel on 1 January 1800,[13] he was posted with his regiment to Ireland in 1802 and took part in the suppression of Robert Emmet's insurrection in 1803.[9] Promoted to major-general on 2 November 1805,[14] he was given command of a cavalry brigade at Weymouth.[9]

Peninsular War

Cotton was elected

After fighting at the

Cotton went on to fight at the Battle of the Pyrenees in July 1813, the Battle of Orthez in February 1814 and the Battle of Toulouse in April 1814.[9] For these services he was raised to the peerage as Baron Combermere in the county palatine of Chester on 3 May 1814[21] and advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath on 4 January 1815.[22]

1815–1822

Cotton was not present at the

Cotton became

Cotton is mentioned in unverified stories of the Chase Vault as being a witness to its allegedly "moving coffins" while serving as Governor of Barbados.[28] Between 1814 and 1820, Cotton undertook an extensive remodelling of his home, Combermere Abbey, including Gothic ornamentation of the Abbot's House and the construction of Wellington's Wing (now demolished) to mark Wellington's visit to the house in 1820.[29] He was appointed the last Governor of Sheerness in January 1821[30] and became Commander-in-Chief, Ireland in 1822.[31]

1825–30

Having been promoted to full

Post 1850

He succeeded Wellington as

Cotton also served as honorary colonel of the

Slave ownership

According to the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, Combermere was paid compensation as a slave owner by the British government in the aftermath of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. Combermere was associated with two claims in 1835 and 1836, which together were awarded £7,195 in payment (worth £726,445 in 2024)[42] for a total of 420 enslaved people on his estates on Saint Kitts and Nevis.[43][44][45]

Family

Combermere was married three times:

- On 1 January 1801, Lady Anna Maria Clinton (d. 31 May 1807), daughter of Thomas Pelham-Clinton, 3rd Duke of Newcastle. They had three children:[41]

- Robert Henry Stapleton Cotton (18 January 1802 – 1821)

- a son who died young

- another son who died young.

- On 22 June 1814,[46] Caroline Greville (d. 25 January 1837), daughter of Captain William Fulke Greville. They had three children:[41]

- Wellington Henry Stapleton-Cotton, 2nd Viscount Combermere(1818–1891)

- Hon. Caroline Stapleton-Cotton (b. 1815), who in 1837 married Arthur Hill, 4th Marquess of Downshire

- Hon. Meliora Emily Anna Maria Cotton, who on 18 June 1853 married John Charles Frederick Hunter

- In 1838, Mary Woolley (née Gibbings), by whom he had no issue.[5]

References

- ^ Shand 1902, p. 394.

- ^ a b Stapleton Cotton, Stapleton Cotton & Knollys 1866, p. 25.

- ^ Chichester 1887, pp. 316–319.

- ^ Stapleton Cotton, Stapleton Cotton & Knollys 1866, p. 30.

- ^ required.)

- ^ "No. 13297". The London Gazette. 5 April 1791. p. 213.

- ^ "No. 13347". The London Gazette. 27 September 1791. p. 542.

- ^ Heathcote, p. 94

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Heathcote, p. 95

- ^ "No. 13707". The London Gazette. 23 September 1794. p. 973.

- ISBN 978-1-4738-1532-2.

- ^ "No. 15231". The London Gazette. 15 February 1800. p. 153.

- ^ "No. 15218". The London Gazette. 31 December 1799. p. 1.

- ^ "No. 15856". The London Gazette. 29 October 1805. p. 1341.

- ^ "No. 16029". The London Gazette. 16 May 1807. p. 657.

- ^ "No. 16556". The London Gazette. 28 December 1811. p. 2498.

- ^ Barthorp 1990, p. 14.

- ^ "No. 16633". The London Gazette. 16 August 1812. p. 1633.

- ^ "No. 16636". The London Gazette. 18 August 1812. p. 1677.

- ^ "No. 16711". The London Gazette. 13 March 1813. p. 531.

- ^ "No. 16894". The London Gazette. 3 May 1814. p. 936.

- ^ "No. 16972". The London Gazette. 4 January 1815. p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Heathcote, p. 96

- ^ "No. 17235". The London Gazette. 29 March 1817. p. 786.

- ^ The Royal Military Calendar or Army Service and Commission Book, Third Edition, Vol. V, 1820. p. 333.

- ^ Slave Trade. Three Volumes. (Vol.2.) Papers Relating to Slaves in the Colonies; Slaves Manumitted; Slaves Imported, Exported; Manumissions, Marriages; Slave Trade at the Mauritius; Apprenticed Africans; Captured negroes at Tortola, St. Christopher's, and Demerara; etc. Session: 21 November 1826 – 2 July 1827: Vol XXII. House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, 1826–1827. p. Slave Trade: Papers Relating To, p. 54.

- S2CID 144301729.

- ^ "Lord Combermere's Ghost". Combermere Abbey. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Callander Beckett S (2004) 'A Brief History of Combermere Abbey' (pamphlet)

- ^ "No. 17676". The London Gazette. 3 February 1821. p. 289.

- ^ "No. 18130". The London Gazette. 23 April 1825. p. 700.

- ^ a b "Viscount Combermere". The Daily Telegraph. 16 November 2000. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Burke 1869, p. 254.

- ^ Murray 1878, p. 486.

- ^ "No. 21366". The London Gazette. 12 October 1852. p. 2663.

- ^ "No. 21792". The London Gazette. 2 October 1855. p. 3652.

- ^ "No. 22542". The London Gazette. 27 August 1861. p. 3501.

- ^ "No. 17676". The London Gazette. 3 February 1821. p. 288.

- ^ "No. 18614". The London Gazette. 25 September 1829. p. 1765.

- ^ Historic England. "Equestrian statue of Stapleton Cotton Viscount Combermere (1376255)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Cottons of Combermere Abbey". Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Stapleton Cotton, 1st Viscount Combermere". University College London. Retrieved on 20 March 2019.

- ^ "Details of Claim | St Kitts 329 (Stapletons)". www.ucl.ac.uk. Legacies of British Slavery. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Details of Claim | Nevis 102 (Stapleton's Estates of Maddens/Russels Rest)". www.ucl.ac.uk. Legacies of British Slavery. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Marriage Register of St Mary Lambeth.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-85045-299-0.

- Burke, Bernard (1869). A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. London: Harrison.

- Heathcote, Tony (1999). The British Field Marshals, 1736–1997: A Biographical Dictionary. Barnsley: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-696-5.

- Murray, John (1878). Handbook for England and Wales: Alphabetically Arranged for the Use of Travellers ... J. Murray.

- Shand, Alexander Innes (1902). Wellington's Lieutenants. Smith, Elder & Company.

- Stapleton Cotton, Mary Woolley; Stapleton Cotton, Stapleton; Knollys, William Wallingford (1866). Memoirs and Correspondence of Field-marshal Viscount Combermere, from his family papers, by Mary Viscountess Combermere and W.W. Knollys.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chichester, Henry Manners (1887). "Cotton, Stapleton". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 12. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chichester, Henry Manners (1887). "Cotton, Stapleton". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 12. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Viscount Combermere

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 751.

- "Archival material relating to Stapleton Cotton, 1st Viscount Combermere". UK National Archives.