Ueno Park

| Ueno Park | |

|---|---|

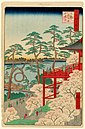

cherry blossoms | |

| |

| Location | Taitō, Tokyo, Japan |

| Coordinates | 35°42′44″N 139°46′16″E / 35.71222°N 139.77111°E |

| Area | 538,506.96 square metres (133.06797 acres) |

| Created | 19 October 1873[1] |

| Public transit access |

|

Ueno Park (上野公園, Ueno Kōen) is a spacious public park in the

History

Ueno Park occupies land once belonging to

Various proposals were put forward for the use of the site as a medical school or hospital, but

Later that year Ueno Park was established, alongside

Natural features

The park has some 8,800 trees, including

The central island houses a shrine to

In all there are some eight hundred cherry trees in the park, although with the inclusion of those belonging to the Ueno Tōshō-gū shrine, temple buildings, and other neighbouring points the total reaches some twelve hundred.[11] Inspired, Matsuo Bashō wrote "cloud of blossoms - is the temple bell from Ueno or Asakusa".[15]

Cultural facilities

Ueno Park is home to a number of museums. The very words in

The

Other museums include the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, dating back to 1926, and Shitamachi Museum of 1980, which is dedicated to the culture of the "Low City".[25][26]

The park was also chosen as home for the Japan Academy (1879), Tokyo School of Fine Arts (1889), and Tokyo School of Music (1890).[2]

The first western-style concert hall in the country, the

The Imperial Library was established as the national library in 1872 and opened in Ueno Park in 1906; the National Diet Library opened in Chiyoda in 1948 and the building now houses the International Library of Children's Literature.[30][31]

Other landmarks

Tokugawa Ieyasu is enshrined at Ueno Tōshō-gū, dating to 1651.[32]

Flame of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Memorial: On the right of the alley leading North to

Gojōten Jinja is dedicated to scholar

One of the lanterns that is present at the park is a

Education

Taito City Board of Education operates public elementary and junior high schools.

Uenokoen 1-11-ban are zoned to Shinobugaoka Elementary School (忍岡小学校), while 12-18-ban are zoned to Negishi Elementary School (根岸小学校).[37]

Part of Uenokoen (1-14 ban and parts of 15-17 ban) is zoned to Ueno Junior High School (上野中学校), while another part (18-ban and the rest of 15-17 ban) is zoned to Shinobugaoka Junior High School (忍岡中学校).[38]

Squatting

Many

Access

- From the east (convenient access to the main park and most museums):

JU JK JY JJ G H Ueno Station

JU JK JY JJ G H Ueno Station

- From the southeast (convenient access to the main park and Shinobazu Pond):

- KS Keisei Ueno Station (located beneath the park)

- JK JY Okachimachi Station

- G Ueno-hirokoji Station

- E Ueno-okachimachi Station

- H Naka-okachimachi Station

- From the southwest (convenient access to Shinobazu Pond):

- From the northwest (convenient access to Shinobazu Pond and Ueno Zoo):

- From the north (convenient access to the Tokyo National Museum):

- JK JY Uguisudani Station

Gallery of main attractions

-

Sōgakudō Concert Hall

-

The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts

-

Ueno Royal Museum

-

Kan'ei-ji Hondō

-

KiyomizuKannondō

-

Tokugawa mausoleum

-

Gojōten Jinja (HanazonoInariJinja)

-

Statue of Saigō Takamori walking his dog

-

Equestrian statue of Prince Komatsu Akihito

-

Statue of Hideyo Noguchi

-

Remains of the Ueno Daibutsu

-

Monument to the Shōgitai

-

Monument to Ulysses Grant

-

Kuroda Memorial Hall,National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo

See also

- Parks and gardens in Tokyo

- National Parks of Japan

- World Heritage Sites in Japan

- Meiji period

References

- ^ a b 上野恩賜公園 [Ueno Park] (in Japanese). Tokyo Metropolis. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8248-3477-7.

- ISBN 0-520-07135-2.

- ^ "旧寛永寺五重塔" [Former Kan'ei-ji five-storey pagoda]. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "寛永寺清水堂" [Kan'ei-ji Shimizudō]. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "寛永寺旧本坊表門 (黒門)" [Former Kan'ei-ji Omotemon (Kuromon)]. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-4-8053-1024-3.

- ^ a b c d e "Ueno Park". National Diet Library. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ISBN 4-7700-1971-8.

- ^ a b c d "Ueno Park" (PDF). Tokyo Metropolis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "Japan - Introduction" (PDF). Ramsar. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ ISBN 0-520-07135-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-4-8053-1024-3.

- ISBN 978-4-7700-3063-4.

- ISBN 978-4-8053-1024-3.

- ^ 歴史 [History] (in Japanese). Seiyōken. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-2959-8777-4.

- ^ "History of the TNM". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "Profile and History of NMNS". National Museum of Nature and Science. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "Outline". National Museum of Western Art. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "Matsukata Collection". National Museum of Western Art. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ISBN 3-930698-93-5.

- ^ "Main Building of the National Museum of Western Art". UNESCO. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ 東京都美術館について [Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum - About] (in Japanese). Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Taitō Ward. Archived from the originalon 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ISBN 0-8348-0288-0.

- ^ "旧東京音楽学校奏楽堂" [Former Tokyo School of Music Sōgakudō]. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Tokyo Bunka Kaikan - About". Tokyo Bunka Kaikan. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "History". National Diet Library. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "History". International Library of Children's Literature. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ 上野東照宮 [Ueno Tōshō-gū] (in Japanese). Ueno Tōshō-gū. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Gojōten Jinja" (in Japanese). Gojōten Jinja. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ 花園稲荷神社 [Hanazono Inari Jinja] (in Japanese). Gojōten Jinja. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "1883年・JR上野駅開業" [1883 - Opening of Ueno Station] (in Japanese). Nishinippon Shimbun. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Japanese Stone Lantern". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "台東区立小学校通学区域表" (PDF). City of Taito. Retrieved 2022-10-09.

- ^ "台東区立中学校通学区域表" (PDF). City of Taito. Retrieved 2022-10-09.

- ^ Margolis, Abby Rachel. "Samurai Beneath Blue Tarps: Doing homelessness, rejecting marginality and preserving nation in Ueno Park (Japan)". University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

External links

- Ueno Park - Pamphlet

- (in Japanese) Ueno Park - Map

- (in Japanese) Ueno Park - Official Site