User:HistoryofIran/Xerxes I

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user in whose space this page is located may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:HistoryofIran/Xerxes_I. |

| Xerxes I 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 | |

|---|---|

Artaxerxes I | |

| Born | c. 518 BC |

| Died | August 465 BC (aged approximately 53) |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Amestris |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Achaemenid |

| Father | Darius the Great |

| Mother | Atossa |

| Religion | Indo-Iranian religion (possibly Zoroastrianism) |

| ||||||||||||||

| Xerxes (Xašayaruša/Ḫašayaruša)[2] in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Xerxes I (

Inheriting a vast empire stretching from Libya to Bactria, Xerxes spent his early years consolidating his power and suppressing a revolt in Egypt and then subsequently Babylonia.

Xerxes is identified with the fictional king Ahasuerus in the biblical Book of Esther.[3]

Etymology

Xérxēs (Ξέρξης) is the

Historiography

Much of Xerxes' bad reputation is due to propaganda by the Macedonian king Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BC), who had him vilified.[6] The modern historian Richard Stoneman regards the portrayal of Xerxes as more nuanced and tragic in the work of the contemporary Greek historian Herodotus.[6] However, many modern historians agree that Herodotus recorded spurious information.[7][8] Pierre Briant has accused him of presenting a stereotyped and biased portrayal of the Persians.[9] Many Achaemenid-era clay tablets and other reports written in Elamite, Akkadian, Egyptian and Aramaic are frequently contradictory to the reports of classical authors, i.e. Ctesias, Plutarch and Justin.[10] However, without these historians, a lot of information regarding the Achaemenid Empire is missing.[11]

Early life

Parentage and birth

Xerxes' father was Darius the Great (r. 522 – 486 BC), the incumbent monarch of the Achaemenid Empire, albeit himself not a member of the family of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the empire.[12][13] His mother was Atossa, a daughter of Cyrus.[14] They had married in 522 BC,[15] with Xerxes being born in c. 518 BC.[16]

Upbringing and education

According to the Greek dialogue

This account of education amongst the Persian elite is supported by

Accession to the throne

After becoming aware of the Persian defeat at the Battle of Marathon, Darius began planning another expedition against the Greek-city states; this time, he, not Datis, would command the imperial armies.[21] Darius had spent three years preparing men and ships for war when a revolt broke out in Egypt. This revolt in Egypt worsened his failing health and prevented the possibility of his leading another army.[21] Soon after, Darius died. In October 486 BCE, the body of Darius was embalmed and entombed in the rock-cut tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam, which he had been preparing.[21] Xerxes succeeded to the throne; however, prior to his accession, he contested the succession with his elder half-brother Artobarzanes, Darius's eldest son who was born to his first wife before Darius rose to power.[22] With Xerxes' accession, the empire was again ruled by a member of the house of Cyrus.[21]

Consolidation of power

At Xerxes' accession, trouble was brewing in some of his domains. A revolt occurred in

Two years later, Babylon produced another rebel leader,

Using texts written by classical authors, it is often assumed that Xerxes enacted a brutal vengeance on Babylon following the two revolts. According to ancient writers, Xerxes destroyed Babylon's fortifications and damaged the temples in the city.[25] The Esagila was allegedly exposed to great damage and Xerxes allegedly carried the statue of Marduk away from the city,[28] possibly bringing it to Iran and melting it down (classical authors held that the statue was entirely made of gold, which would have made melting it down possible).[25] Modern historian Amélie Kuhrt considers it unlikely that Xerxes destroyed the temples, but believes that the story of him doing so may derive from an anti-Persian sentiment among the Babylonians.[29] It is doubtful if the statue was removed from Babylon at all[25] and some have even suggested that Xerxes did remove a statue from the city, but that this was the golden statue of a man rather than the statue of the god Marduk.[30][31] Though mentions of it are lacking considerably compared to earlier periods, contemporary documents suggest that the Babylonian New Year's Festival continued in some form during the Achaemenid period.[32] Because the change in rulership from the Babylonians themselves to the Persians and due to the replacement of the city's elite families by Xerxes following its revolt, it is possible that the festival's traditional rituals and events had changed considerably.[33]

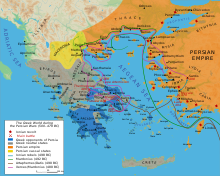

Invasion of Greece

Death

Xerxes was killed alongside his son and designated successor

Government

Building projects

Religion

While there is no general consensus in scholarship whether Xerxes and his predecessors had been influenced by Zoroastrianism,[36] it is well established that Xerxes was a firm believer in Ahura Mazda, whom he saw as the supreme deity.[36] However, Ahura Mazda was also worshipped by adherents of the (Indo-)Iranian religious tradition.[36][37] On his treatment of other religions, Xerxes followed the same policy as his predecessors; he appealed to local religious scholars, made sacrifices to local deities, and destroyed temples in cities and countries that caused disorder.[38]

Legacy

Ancestry

Notes

References

- Darius I.

- ISBN 3-8053-2310-7, pp. 220–221

- ^ Stoneman 2015, p. 9.

- ^ a b Marciak 2017, p. 80; Schmitt 2000

- ^ Schmitt 2000.

- ^ a b Stoneman 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Radner 2013, p. 454.

- ^ Briant 2002, pp. 158, 516.

- ^ Stoneman 2015, pp. viii–ix.

- ^ Stoneman 2015, p. ix.

- ^ Llewellyn-Jones 2017, p. 70.

- ^ Waters 1996, pp. 11, 18.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 132.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 520.

- ^ Stoneman 2015, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Stoneman 2015, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Stoneman 2015, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Stoneman 2015, p. 29.

- ^ a b Dandamayev 1989, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Shahbazi 1994, pp. 41–50.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Briant 2002, p. 525.

- ^ Dandamayev 1983, p. 414.

- ^ a b c d e Dandamayev 1993, p. 41.

- ^ Stoneman 2015, p. 111.

- ^ Dandamayev 1989, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Sancisi-Weerdenburg 2002, p. 579.

- ^ Deloucas 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Waerzeggers & Seire 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 544.

- ^ Deloucas 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Deloucas 2016, p. 41.

- ^ a b Dandamayev 1989, p. 188.

- ^ a b Llewellyn-Jones 2017, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Malandra 2005.

- ^ Boyce 1984, pp. 684–687.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 549.

Sources

- Bachenheimer, Avi (2018). Old Persian: Dictionary, Glossary and Concordance. Wiley and Sons. pp. 1–799.

- ISBN 9780415239028.

- Boyce, Mary (1984). "Ahura Mazdā". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 7. pp. 684–687.

- ISBN 9781575061207.

- Brosius, Maria (2000). "Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. London et al.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (2000). "Achaemenid taxation". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ISBN 978-9004091726.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link - Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1993). "Xerxes and the Esagila Temple in Babylon". JSTOR 24048423.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link - Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1990). "Cambyses II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 7. pp. 726–729.

- Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1983). "Achaemenes". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 4. p. 414.

- Deloucas, Andrew Alberto Nicolas (2016). "Balancing Power and Space: a Spatial Analysis of the Akītu Festival in Babylon after 626 BCE" (PDF). Research Master's Thesis for Classical and Ancient Civilizations (Assyriology). Universiteit Leiden.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2017). "The Achaemenid Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 9780692864401.

- Malandra, William W. (2005). "Zoroastrianism i. Historical review up to the Arab conquest". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Marciak, Michał (2017). Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene: Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West. BRILL. ISBN 9789004350724.

- Radner, Karen (2013). "Assyria and the Medes". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.

- Sancisi-Weerdenburg, Heleen (2002). "The Personality of Xerxes, King of Kings". Brill's Companion to Herodotus. BRILL. pp. 579–590. ISBN 9789004217584.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link - Schmitt, Rüdiger (2000). "Xerxes i. The Name". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Shahbazi, Shapur (1994), "Darius I the Great", Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 7, New York: Columbia University, pp. 41–50

- Stoneman, Richard (2015). Xerxes: A Persian Life. Yale University Press. pp. 1–288. ISBN 9781575061207.

- Waerzeggers, Caroline; Seire, Maarja (2018). Xerxes and Babylonia: The Cuneiform Evidence (PDF). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-3670-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link - Waters, Matt (1996). "Darius and the Achaemenid Line". London: 11–18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)