Achaemenid Empire

Achaemenid Empire 𐎧𐏁𐏂 Xšāça | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 BC-330 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 336–330 BC | Darius III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Persian Revolt | 550 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 547 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 539 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 535–518 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 525 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 513 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 499–449 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 484 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 395–387 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 372–362 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 343 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 330 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 500 BC[12][13] | 5,500,000 km2 (2,100,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 500 BC[14] | 17 million to 35 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | siglos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire,

Around the 7th century BC, the region of

In the modern era, the Achaemenid Empire has been recognized for its imposition of a successful model of centralized bureaucratic administration, its multicultural policy, building complex infrastructure such as

By 330 BC, the Achaemenid Empire was conquered by Alexander the Great, an ardent admirer of Cyrus; the conquest marked a key achievement in the then-ongoing campaign of his Macedonian Empire.[22][23] Alexander's death marks the beginning of the Hellenistic period, when most of the fallen Achaemenid Empire's territory came under the rule of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and the Seleucid Empire, both of which had emerged as successors to the Macedonian Empire following the Partition of Triparadisus in 321 BC. Hellenistic rule remained in place for almost a century before the Iranian elites of the central plateau reclaimed power under the Parthian Empire.[20]

Etymology

The Achaemenid Empire borrows its name from the ancestor of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the empire,

Around 850 BC the original nomadic people who began the empire called themselves the Parsa and their constantly shifting territory Parsua, for the most part localized around Persis.

History

Timeline

Origin of the Achaemenid dynasty

The Persian nation contains a number of tribes as listed here. ... : the

The Achaemenid Empire was created by nomadic

The Achaemenids were initially rulers of the Elamite city of Anshan near the modern city of Marvdasht;[30] the title "King of Anshan" was an adaptation of the earlier Elamite title "King of Susa and Anshan".[31] There are conflicting accounts of the identities of the earliest Kings of Anshan. According to the Cyrus Cylinder (the oldest extant genealogy of the Achaemenids) the kings of Anshan were Teispes, Cyrus I, Cambyses I and Cyrus II, also known as Cyrus the Great, who founded the empire.[30] The later Behistun Inscription, written by Darius the Great, claims that Teispes was the son of Achaemenes and that Darius is also descended from Teispes through a different line, but no earlier texts mention Achaemenes.[32] In Herodotus' Histories, he writes that Cyrus the Great was the son of Cambyses I and Mandane of Media, the daughter of Astyages, the king of the Median Empire.[33]

Formation and expansion

550s BC

Cyrus revolted against the Median Empire in 553 BC, and in 550 BC succeeded in defeating the Medes, capturing Astyages and taking the Median capital city of Ecbatana.[34][35][36] Once in control of Ecbatana, Cyrus styled himself as the successor to Astyages and assumed control of the entire empire.[37] By inheriting Astyages' empire, he also inherited the territorial conflicts the Medes had had with both Lydia and the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[38]

540s BC

King Croesus of Lydia sought to take advantage of the new international situation by advancing into what had previously been Median territory in Asia Minor.[39][40] Cyrus led a counterattack which not only fought off Croesus' armies, but also led to the capture of Sardis and the fall of the Lydian Kingdom in 546 BC.[41][42][c] Cyrus placed Pactyes in charge of collecting tribute in Lydia and left, but once Cyrus had left Pactyes instigated a rebellion against Cyrus.[42][43][44] Cyrus sent the Median general Mazares to deal with the rebellion, and Pactyes was captured. Mazares, and after his death Harpagus, set about reducing all the cities which had taken part in the rebellion. The subjugation of Lydia took about four years in total.[45]

When the power in Ecbatana changed hands from the Medes to the Persians, many tributaries to the Median Empire believed their situation had changed and revolted against Cyrus.

530s BC

Nothing is known of Persia–Babylon relations between 547 and 539 BC, but it is likely that there were hostilities between the two empires for several years leading up to the war of 540–539 BC and the

520s BC

In 530 BC, Cyrus died, presumably while on a military expedition against the Massagetae in Central Asia. He was succeeded by his eldest son Cambyses II, while his younger son Bardiya[d] received a large territory in Central Asia.[62][63] By 525 BC, Cambyses had successfully subjugated Phoenicia and Cyprus and was making preparations to invade Egypt with the newly created Persian navy.[64][65] Pharaoh Amasis II had died in 526, and had been succeeded by Psamtik III, resulting in the defection of key Egyptian allies to the Persians.[65] Psamtik positioned his army at Pelusium in the Nile Delta. He was soundly defeated by the Persians in the Battle of Pelusium before fleeing to Memphis, where the Persians defeated him and took him prisoner. After attempting a failed revolt, Psamtik III promptly committed suicide.[65][66]

Herodotus depicts Cambyses as openly antagonistic to the Egyptian people and their gods, cults, temples, and priests, in particular stressing the murder of the sacred bull Apis.[67] He says that these actions led to a madness that caused him to kill his brother Bardiya (who Herodotus says was killed in secret),[68] his own sister-wife[69] and Croesus of Lydia.[70] He then concludes that Cambyses completely lost his mind,[71] and all later classical authors repeat the themes of Cambyses' impiety and madness. However, this is based on spurious information, as the epitaph of Apis from 524 BC shows that Cambyses participated in the funeral rites of Apis styling himself as pharaoh.[72]

Following the conquest of Egypt, the Libyans and the Greeks of Cyrene and Barca in present-day eastern Libya (Cyrenaica) surrendered to Cambyses and sent tribute without a fight.[65][66] Cambyses then planned invasions of Carthage, the oasis of Ammon and Ethiopia.[73] Herodotus claims that the naval invasion of Carthage was canceled because the Phoenicians, who made up a large part of Cambyses' fleet, refused to take up arms against their own people,[74] but modern historians doubt whether an invasion of Carthage was ever planned at all.[65] However, Cambyses dedicated his efforts to the other two campaigns, aiming to improve the Empire's strategic position in Africa by conquering the Kingdom of Meroë and taking strategic positions in the western oases. To this end, he established a garrison at Elephantine consisting mainly of Jewish soldiers, who remained stationed at Elephantine throughout Cambyses' reign.[65] The invasions of Ammon and Ethiopia themselves were failures. Herodotus claims that the invasion of Ethiopia was a failure due to the madness of Cambyses and the lack of supplies for his men,[75] but archaeological evidence suggests that the expedition was not a failure, and a fortress at the Second Cataract of the Nile, on the border between Egypt and Kush, remained in use throughout the Achaemenid period.[65][76]

The events surrounding Cambyses's death and Bardiya's succession are greatly debated as there are many conflicting accounts.[61] According to Herodotus, as Bardiya's assassination had been committed in secret, the majority of Persians still believed him to be alive. This allowed two Magi to rise up against Cambyses, with one of them sitting on the throne able to impersonate Bardiya because of their remarkable physical resemblance and shared name (Smerdis in Herodotus's accounts[d]).[77] Ctesias writes that when Cambyses had Bardiya killed he immediately put the magus Sphendadates in his place as satrap of Bactria due to a remarkable physical resemblance.[78] Two of Cambyses' confidants then conspired to usurp Cambyses and put Sphendadates on the throne under the guise of Bardiya.[79] According to the Behistun Inscription, written by the following king Darius the Great, a magus named Gaumata impersonated Bardiya and incited a revolution in Persia.[60] Whatever the exact circumstances of the revolt, Cambyses heard news of it in the summer of 522 BC and began to return from Egypt, but he was wounded in the thigh in Syria and died of gangrene, so Bardiya's impersonator became king.[80][e] The account of Darius is the earliest, and although the later historians all agree on the key details of the story, that a magus impersonated Bardiya and took the throne, this may have been a story created by Darius to justify his own usurpation.[82] Iranologist Pierre Briant hypothesises that Bardiya was not killed by Cambyses, but waited until his death in the summer of 522 BC to claim his legitimate right to the throne as he was then the only male descendant of the royal family. Briant says that although the hypothesis of a deception by Darius is generally accepted today, "nothing has been established with certainty at the present time, given the available evidence".[83]

According to the

Herodotus writes[85] that the native leadership debated the best form of government for the empire.

510s BC

Ever since the

5th century BC

By the 5th century BC, the Kings of Persia were either ruling over or had subordinated territories encompassing not just all of the

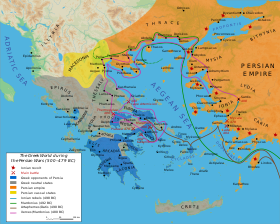

Greco-Persian Wars

The

The Persians continued to reduce the cities along the west coast that still held out against them, before finally imposing a peace settlement in 493 BC on Ionia that was generally considered to be both just and fair. The

Xerxes I (485–465 BC, Old Persian Xšayārša "Hero Among Kings"), son of Darius I, vowed to complete the job. He organized a massive invasion aiming to conquer Greece. His army entered Greece from the north in the spring of 480 BC, meeting little or no resistance through Macedonia and Thessaly, but was delayed by a small Greek force for three days at Thermopylae. A simultaneous naval battle at Artemisium was tactically indecisive as large storms destroyed ships from both sides. The battle was stopped prematurely when the Greeks received news of the defeat at Thermopylae and retreated. The battle was a tactical victory for the Persians, giving them uncontested control of Artemisium and the Aegean Sea.[citation needed]

Following his victory at the

Cultural phase and Zoroastrian reforms

After

After Persia had been defeated at the

Artaxerxes offered

When Artaxerxes died in 424 BC at

From 412 BC

Artaxerxes II became involved in a war with Persia's erstwhile allies, the

In 358 BC Artaxerxes II died and was succeeded by his son

Artaxerxes III then ordered the disbanding of all the satrapal armies of Asia Minor, as he felt that they could no longer guarantee peace in the west and was concerned that these armies equipped the western satraps with the means to revolt.]

In 343 BC, Artaxerxes committed responsibility for the suppression of the Cyprian rebels to

After this, Artaxerxes personally led an army of 330,000 men against Sidon. Artaxerxes' army comprised 300,000-foot soldiers, 30,000 cavalry, 300 triremes, and 500 transports or provision ships. After gathering this army, he sought assistance from the Greeks. Though refused aid by Athens and Sparta, he succeeded in obtaining a thousand Theban heavy-armed hoplites under Lacrates, three thousand Argives under Nicostratus, and six thousand Æolians, Ionians, and Dorians from the Greek cities of Asia Minor. This Greek support was numerically small, amounting to no more than 10,000 men, but it formed, together with the Greek mercenaries from Egypt who went over to him afterward, the force on which he placed his chief reliance, and to which the ultimate success of his expedition was mainly due. The approach of Artaxerxes sufficiently weakened the resolution of Tennes that he endeavoured to purchase his own pardon by delivering up 100 principal citizens of Sidon into the hands of the Persian king and then admitting Artaxerxes within the defences of the town. Artaxerxes had the 100 citizens transfixed with javelins, and when 500 more came out as supplicants to seek his mercy, Artaxerxes consigned them to the same fate. Sidon was then burnt to the ground, either by Artaxerxes or by the Sidonian citizens. Forty thousand people died in the conflagration.[117] Artaxerxes sold the ruins at a high price to speculators, who calculated on reimbursing themselves by the treasures which they hoped to dig out from among the ashes.[118] Tennes was later put to death by Artaxerxes.[119] Artaxerxes later sent Jews who supported the revolt to Hyrcania on the south coast of the Caspian Sea.[120][121]

Second conquest of Egypt

The reduction of Sidon was followed closely by the invasion of Egypt. In 343 BC, Artaxerxes III, in addition to his 330,000 Persians, had now a force of 14,000 Greeks furnished by the Greek cities of Asia Minor: 4,000 under Mentor, consisting of the troops that he had brought to the aid of Tennes from Egypt; 3,000 sent by Argos; and 1,000 from Thebes. He divided these troops into three bodies, and placed at the head of each a Persian and a Greek. The Greek commanders were Lacrates of Thebes, Mentor of Rhodes and Nicostratus of Argos while the Persians were led by Rhossaces, Aristazanes, and Bagoas, the chief of the eunuchs. Nectanebo II resisted with an army of 100,000 of whom 20,000 were Greek mercenaries. Nectanebo II occupied the Nile and its various branches with his large navy.[citation needed]

The character of the country, intersected by numerous canals and full of strongly fortified towns, was in his favour and Nectanebo II might have been expected to offer a prolonged, if not even a successful resistance. However, he lacked good generals, and, over-confident in his own powers of command, he was out-maneuvered by the Greek mercenary generals, and his forces were eventually defeated by the combined Persian armies. After his defeat, Nectanebo hastily fled to Memphis, leaving the fortified towns to be defended by their garrisons. These garrisons consisted of partly Greek and partly Egyptian troops; between whom jealousies and suspicions were easily sown by the Persian leaders. As a result, the Persians were able to rapidly reduce numerous towns across Lower Egypt and were advancing upon Memphis when Nectanebo decided to quit the country and flee southwards to Ethiopia.[117] The Persian army completely routed the Egyptians and occupied the Lower Delta of the Nile. Following Nectanebo fleeing to Ethiopia, all of Egypt submitted to Artaxerxes. The Jews in Egypt were sent either to Babylon or to the south coast of the Caspian Sea, the same location that the Jews of Phoenicia had earlier been sent.[citation needed]

After this victory over the Egyptians, Artaxerxes had the city walls destroyed, started a reign of terror, and set about looting all the temples.

After his success in Egypt, Artaxerxes returned to Persia and spent the next few years effectively quelling insurrections in various parts of the Empire so that a few years after his conquest of Egypt, the Persian Empire was firmly under his control. Egypt remained a part of the Persian Empire from then until Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt.[citation needed]

After the conquest of Egypt, there were no more revolts or rebellions against Artaxerxes. Mentor and Bagoas, the two generals who had most distinguished themselves in the Egyptian campaign, were advanced to posts of the highest importance. Mentor, who was governor of the entire Asiatic seaboard, was successful in reducing to subjection many of the chiefs who during the recent troubles had rebelled against Persian rule. In the course of a few years, Mentor and his forces were able to bring the whole Asian Mediterranean coast into complete submission and dependence.[citation needed]

Bagoas went back to the Persian capital with Artaxerxes, where he took a leading role in the internal administration of the Empire and maintained tranquillity throughout the rest of the Empire. During the last six years of the reign of Artaxerxes III, the Persian Empire was governed by a vigorous and successful government.[117]

The Persian forces in Ionia and Lycia regained control of the Aegean and the Mediterranean Sea and took over much of Athens' former island empire. In response, Isocrates of Athens started giving speeches calling for a 'crusade against the barbarians' but there was not enough strength left in any of the Greek city-states to answer his call.[123]

Although there were no rebellions in the Persian Empire itself, the growing power and territory of

In 338 BC Artaxerxes was poisoned by Bagoas with the assistance of a physician.[125]

Fall to Alexander III of Macedon

Artaxerxes III was succeeded by

In the ensuing chaos created by Alexander's invasion of Persia, Cyrus's tomb was broken into and most of its luxuries were looted. When Alexander reached the tomb, he was horrified by the manner in which it had been treated, and questioned the Magi, putting them on trial.[126][127] By some accounts, Alexander's decision to put the Magi on trial was more an attempt to undermine their influence and display his own power than a show of concern for Cyrus's tomb.[128] Regardless, Alexander the Great ordered Aristobulus to improve the tomb's condition and restore its interior, showing respect for Cyrus.[126] From there he headed to Ecbatana, where Darius III had sought refuge.[129]

Darius III was taken prisoner by Bessus, his Bactrian satrap and kinsman. As Alexander approached, Bessus had his men murder Darius III and then declared himself Darius' successor, as Artaxerxes V, before retreating into Central Asia leaving Darius' body in the road to delay Alexander, who brought it to Persepolis for an honourable funeral. Bessus would then create a coalition of his forces, to create an army to defend against Alexander. Before Bessus could fully unite with his confederates at the eastern part of the empire,[130] Alexander, fearing the danger of Bessus gaining control, found him, put him on trial in a Persian court under his control, and ordered his execution in a "cruel and barbarous manner."[131]

Alexander generally kept the original Achaemenid administrative structure, leading some scholars to dub him as "the last of the Achaemenids".[132] Upon Alexander's death in 323 BC, his empire was divided among his generals, the Diadochi, resulting in a number of smaller states. The largest of these, which held sway over the Iranian plateau, was the Seleucid Empire, ruled by Alexander's general Seleucus I Nicator. Native Iranian rule would be restored by the Parthians of northeastern Iran over the course of the 2nd century BC through the Parthian Empire.[133]

Descendants in later Persian dynasties

- "Frataraka" of the Seleucid Empire

Several later Persian rulers, forming the

- Kings of Persis under the Parthian Empire

During an apparent transitional period, corresponding to the reigns of Vādfradād II and another uncertain king, no titles of authority appeared on the reverse of their coins. The earlier title prtrk' zy alhaya (Frataraka) had disappeared. Under

When the

- Sasanian Empire

With the reign of Šābuhr, the son of

- Kingdom of Pontus

The Achaemenid line would also be carried on through the

Both the later dynasties of the Parthians and Sasanians would on occasion claim Achaemenid descent. Recently there has been some corroboration for the Parthian claim to Achaemenid ancestry via the possibility of an inherited disease (neurofibromatosis) demonstrated by the physical descriptions of rulers and from the evidence of familial disease on ancient coinage.[141]

Government

Cyrus the Great founded the empire as a multi-state empire, governed from four capital cities: Pasargadae, Babylon, Susa and Ecbatana. The Achaemenids allowed a certain amount of regional autonomy in the form of the satrapy system. A satrapy was an administrative unit, usually organized on a geographical basis. A 'satrap' (governor) was the governor who administered the region, a 'general' supervised military recruitment and ensured order, and a 'state secretary' kept the official records. The general and the state secretary reported directly to the satrap as well as the central government. At differing times, there were between 20 and 30 satrapies.

Cyrus the Great created an organized army including the

Also, many seals and seal impressions are found in these Persepolis archives. These documents represent administrative activity and flow of data in Persepolis over more than fifty consecutive years (509 to 457 BC).

Coinage

The Persian

Tax districts

Darius also introduced a regulated and sustainable tax system that was precisely tailored to each satrapy, based on their supposed productivity and their economic potential. For instance, Babylon was assessed for the highest amount and for a startling mixture of commodities – 1,000 silver talents, four months' supply of food for the army. India was clearly already fabled for its gold; Egypt was known for the wealth of its crops; it was to be the granary of the Persian Empire (as later of Rome's) and was required to provide 120,000 measures of grain in addition to 700 talents of silver. This was exclusively a tax levied on subject peoples.[151] There is evidence that conquered and rebellious enemies could be sold into slavery.[152] Alongside its other innovations in administration and taxation, the Achaemenids may have been the first government in the ancient Near East to register private slave sales and tax them using an early form of sales tax.[153]

Other accomplishments of Darius' reign included the codification of the dāta (a universal legal system which would become the basis of later Iranian law), and the construction of a new capital at Persepolis.[155][156]

Transportation and communication

Under the Achaemenids, trade was extensive and there was an efficient infrastructure that facilitated the exchange of commodities in the far reaches of the empire. Tariffs on trade, along with agriculture and tribute, were major sources of revenue for the empire.[151][157]

The satrapies were linked by a 2,500-kilometer highway, the most impressive stretch being the Royal Road from Susa to Sardis, built by command of Darius I. It featured stations and caravanserais at specific intervals. The relays of mounted couriers (the angarium) could reach the remotest of areas in fifteen days. Herodotus observes that "there is nothing in the world that travels faster than these Persian couriers. Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night stays these courageous couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds."[158] Despite the relative local independence given by the satrapy system, royal inspectors, the "eyes and ears of the king", toured the empire and reported on local conditions.[citation needed]

Another highway of commerce was the Great Khorasan Road, an informal mercantile route that originated in the fertile lowlands of Mesopotamia and snaked through the Zagros highlands, through the Iranian plateau and Afghanistan into the Central Asian regions of Samarkand, Merv and Ferghana, allowing for the construction of frontier cities like Cyropolis. Following Alexander's conquests, this highway allowed for the spread of cultural syncretic fusions like Greco-Buddhism into Central Asia and China, as well as empires like the Kushan, Indo-Greek and Parthian to profit from trade between East and West. This route was greatly rehabilitated and formalized during the Abbasid Caliphate, during which it developed into a major component of the famed Silk Road.[159]

Military

Despite its humble origins in Persis, the empire reached an enormous size under the leadership of

Ethnic composition

The empire's great armies were, like the empire itself, very diverse, having:

Infantry

The Achaemenid infantry consisted of three groups: the

The

The

The Achaemenids relied heavily on

The

Cavalry

The armoured Persian horsemen and their death dealing chariots were invincible. No man dared face them

The Persian cavalry was crucial for conquering nations and maintained its importance in the Achaemenid army to the last days of the Achaemenid Empire. The cavalry was separated into four groups. The

]

In the later years of the Achaemenid Empire, the chariot archer had become merely a ceremonial part of the Persian army, yet in the early years of the Empire, their use was widespread. The chariot archers were armed with lances, bows, arrows, swords, and

The horses used by the Achaemenids for cavalry were often suited with scale armour, like most cavalry units. The riders often had the same armour as Infantry units, wicker shields, short spears, swords or large daggers, bow and arrow, and scale armour coats. The camel cavalry was different, because the camels and sometimes the riders, were provided little protection against enemies, yet when they were offered protection, they would have lances, swords, bow, arrow, and scale armour. The camel cavalry was first introduced into the Persian army by

Since its foundation by Cyrus, the Persian empire had been primarily a land empire with a strong army but void of any actual naval forces. By the 5th century BC, this was to change, as the empire came across Greek and Egyptian forces, each with their own maritime traditions and capabilities.

At first the ships were built in Sidon by the Phoenicians; the first Achaemenid ships measured about 40 meters in length and 6 meters in width, able to transport up to 300 Persian

The Achaemenid navy established bases located along the Karun, and in Bahrain, Oman, and Yemen. The Persian fleet was not only used for peace-keeping purposes along the Karun but also opened the door to trade with India via the Persian Gulf.[198] Darius's navy was in many ways a world power at the time, but it would be Artaxerxes II who in the summer of 397 BC would build a formidable navy, as part of a rearmament which would lead to his decisive victory at Knidos in 394 BC, re-establishing Achaemenid power in Ionia. Artaxerxes II would also use his navy to later on quell a rebellion in Egypt.[199]

The construction material of choice was wood, but some armoured Achaemenid ships had metallic blades on the front, often meant to slice enemy ships using the ship's momentum. Naval ships were also equipped with hooks on the side to grab enemy ships, or to negotiate their position. The ships were propelled by sails or manpower. The ships the Persians created were unique. As far as maritime engagement, the ships were equipped with two mangonels that would launch projectiles such as stones, or flammable substances.[198]

Xenophon describes his eyewitness account of a massive military bridge created by joining 37 Persian ships across the Tigris. The Persians used each boat's buoyancy to support a connected bridge above which supply could be transferred.[198] Herodotus also gives many accounts of the Persians using ships to build bridges.[200][201]

Darius I, in an attempt to subdue the

Strait called Bosphorus, across which the bridge of Darius had been thrown, is hundred and twenty

Propontis. The Propontis is five hundred furlongs across and fourteen hundred long. Its waters flow into the Hellespont, the length of which is four hundred furlongs ...

Years later, a similar boat bridge would be constructed by Xerxes I, in his invasion of Greece. Although the Persians failed to capture the Greek city-states completely, the tradition of maritime involvement was carried down by the Persian kings, most notably Artaxerxes II. Years later, when Alexander invaded Persia and during his advancement into India, he took a page from the Persian art of war, by having Hephaestion and Perdiccas construct a similar boat-bridge at the Indus river in India in the spring of 327 BC.[204]

Culture

Languages

During the reign of Cyrus II and Darius I, and as long as the seat of government was still at

Following the conquest of

Although Old Persian also appears on some seals and art objects, that language is attested primarily in the Achaemenid inscriptions of Western Iran, suggesting then that Old Persian was the common language of that region. However, by the reign of Artaxerxes II, the grammar and orthography of the inscriptions was so "far from perfect"[211] that it has been suggested that the scribes who composed those texts had already largely forgotten the language, and had to rely on older inscriptions, which they to a great extent reproduced verbatim.[212]

When the occasion demanded, Achaemenid administrative correspondence was conducted in

Customs

Herodotus mentions that the Persians were invited to great birthday feasts (Herodotus, Histories 8), which would be followed by many desserts, a treat which they reproached the Greeks for omitting from their meals. He also observed that the Persians drank wine in large quantities and used it even for counsel, deliberating on important affairs when drunk, and deciding the next day, when sober, whether to act on the decision or set it aside.[213]

Religion

Mithra[214] was worshipped;[215][216] his temples and symbols were the most widespread,[217] most people bore names related to him[218] and most festivals were dedicated to him.[219][220] Religious toleration has been described as a "remarkable feature" of the Achaemenid Empire.[221] The Old Testament reports that Persian king Cyrus the Great released the Jewish people from the Babylonian captivity in 539–530 BC and permitted them to return to their homeland.[222] Cyrus the Great assisted in the restoration of the sacred places of various cities.[221]

It was during the Achaemenid period that

During the reign of Artaxerxes I and Darius II, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote: "[the Persians] have no images of the gods, no temples nor altars, and consider the use of them a sign of folly. This comes, I think, from their not believing the gods to have the same nature with men, as the Greeks imagine."[225] He claims the Persians offer sacrifice to: "the sun and moon, to the earth, to fire, to water, and to the winds. These are the only gods whose worship has come down to them from ancient times. At a later period, they began the worship of Urania, which they borrowed from the Arabians and Assyrians. Mylitta is the name by which the Assyrians know this goddess, to whom the Persians referred as Anahita."[225]

The Babylonian scholar and priest Berosus records—although writing over seventy years after the reign of Artaxerxes II — that the emperor had been the first to make cult statues of divinities and have them placed in temples in many of the major cities of the empire.[226] Berosus also substantiates Herodotus when he says the Persians knew of no images of gods until Artaxerxes II erected those images. On the means of sacrifice, Herodotus adds "they raise no altar, light no fire, pour no libations."[227] Herodotus also observed that "no prayer or offering can be made without a magus present".[227]

Women

The position of women in the Achaemenid Empire differed depending on which culture they belonged to and therefore varied depending on the region. The position of Persian women in actual Persia has traditionally been described from mythological Biblical references and the sometimes biased Ancient Greek sources, neither of them fully reliable as sources, but the most reliable references are the archeological Persepolis Fortification Tablets (PFT), which describes women in connection to the royal court in Persepolis, from royal women to female laborers who were recipients of food rations at Persepolis.[228]

The hierarchy of the royal women at the Persian court was ranked with the king's mother first, followed by the queen and the king's daughters, the king's concubines, and the other women of the royal palace.[228] The king normally married a female member of the royal family or a Persian noblewoman related to a satrap or another important Persian man; it was permitted for members of the royal family to marry relatives, but there is no evidence for marriage between closer family members than half-siblings.[228] The king's concubines were often either slaves, sometimes prisoners of war, or foreign princesses, whom the king did not marry because they were foreigners, and whose children did not have the right to inherit the throne.[228]

Greek sources accuse the king of having hundreds of concubines secluded in a

Royal and aristocratic Achaemenid women were given an education in subjects that did not appear compatible with seclusions, such as horsemanship and archery.[229][230] Royal and aristocratic women held and managed vast estates and workshops and employed large numbers of servants and professional laborers.[231] Royal and aristocratic women do not seem to have lived in seclusion from men, since it is known that they appeared in public[232] and traveled with their husbands,[232] participated in hunting[233] and in feasts:[234] at least the chief wife of a royal or aristocratic man did not live in seclusion, as it is clearly stated that wives customarily accompanied their husbands at dinner banquets, although they left the banquet when the "women entertainers" came in and the men began "merrymaking".[235]

No woman ever ruled the Achaemenid Empire, as monarch or as regent, but some queen's consorts are known to have had influence over the affairs of state, notably Atossa and Parysatis.

There are no evidence of any women being employed as an official in the administration or within religious service, however, there are plenty of archeological evidence of women being employed as free labourers in Persepolis, where they worked alongside men.[228] Women could be employed as the leaders of their workforce, known by the title arraššara pašabena, which were then given a higher salary than the male workers of their workforce;[228] and while female laborers were given less than men, qualified workers within the crafts were given equal pay regardless of their sex.[228]

Architecture and art

Achaemenid architecture included large cities, temples, palaces, and

Achaemenid art includes frieze reliefs, metalwork such as the Oxus Treasure, decoration of palaces, glazed brick masonry, fine craftsmanship (masonry, carpentry, etc.), and gardening. Although the Persians took artists, with their styles and techniques, from all corners of their empire, they did not just produce a combination of styles, but a synthesis of a new unique Persian style.[238]

One of the most remarkable examples of both Achaemenid architecture and art is the grand palace of

Yaka timber was brought from

Chorasmia, the silver and ebony from Egypt, the ornamentation from Ionia, the ivory from Ethiopia and from Sindh and from Arachosia. The stone-cutters who wrought the stone were Ionians and Sardians. The goldsmiths were Medes and Egyptians. The men who wrought the wood were Sardinians and Egyptians. The men who wrought the baked brick were Babylonians. The men who adorned the wall, those were Medes and Egyptians.[citation needed]

-

Reconstruction of thePalace of Darius at Susa. The palace served as a model for Persepolis.

-

Lion on a decorative panel fromDarius I the Great's palace, Louvre

-

Iconic relief of lion and bull fighting,Apadana of Persepolis

-

Achaemenid golden bowl with lioness imagery ofMazandaran, National Museum of Iran

Tombs

Many Achaemenid rulers built tombs for themselves. The most famous,

Legacy

The Achaemenid Empire left a lasting impression on the heritage and cultural identity of Asia and the Middle East, and influenced the development and structure of future empires. In fact, the Greeks, and later on the Romans, adopted the best features of the Persian method of governing an empire.[239] The Persian model of governance was particularly formative in the expansion and maintenance of the Abbasid Caliphate, whose rule is widely considered the period of the 'Islamic Golden Age'. Like the ancient Persians, the Abbasid dynasty centered their vast empire in Mesopotamia (at the newly founded cities of Baghdad and Samarra, close to the historical site of Babylon), derived much of their support from Persian aristocracy and heavily incorporated the Persian language and architecture into Islamic culture.[240] The Achaemenid Empire is noted in Western history as the antagonist of the Greek city-states during the Greco-Persian Wars and for the emancipation of the Jewish exiles in Babylon. The historical mark of the empire went far beyond its territorial and military influences and included cultural, social, technological and religious influences as well. For example, many Athenians adopted Achaemenid customs in their daily lives in a reciprocal cultural exchange,[241] some being employed by or allied to the Persian kings. The impact of the Edict of Cyrus is mentioned in Judeo-Christian texts, and the empire was instrumental in the spread of Zoroastrianism as far east as China. The empire also set the tone for the politics, heritage and history of Iran (also known as Persia).[242] Historian Arnold Toynbee regarded Abbasid society as a "reintegration" or "reincarnation" of Achaemenid society, as the synthesis of Persian, Turkic and Islamic modes of governance and knowledge allowed for the spread of Persianate culture over a wide swath of Eurasia through the Turkic-origin Seljuq, Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires.[240] Historian Bernard Lewis wrote that

The work of Iranians can be seen in every field of cultural endeavor, including Arabic poetry, to which poets of Iranian origin composing their poems in Arabic made a very significant contribution. In a sense, Iranian Islam is a second advent of Islam itself, a new Islam sometimes referred to as Islam-i-Ajam. It was this Persian Islam, rather than the original Arab Islam, that was brought to new areas and new peoples: to the Turks, first in Central Asia and then in the Middle East in the country which came to be called Turkey, and of course to India. The Ottoman Turks brought a form of Iranian civilization to the walls of Vienna. [...] By the time of the great Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century, Iranian Islam had become not only an important component; it had become a dominant element in Islam itself, and for several centuries the main centers of the Islamic power and civilization were in countries that were, if not Iranian, at least marked by Iranian civilization ... The major centers of Islam in the late medieval and early modern periods, the centers of both political and cultural power, such as India, Central Asia, Iran, Turkey, were all part of this Iranian civilization.

The Persian Empire is an empire in the modern sense—like that which existed in Germany, and the great imperial realm under the sway of Napoleon; for we find it consisting of a number of states, which are indeed dependent, but which have retained their own individuality, their manners, and laws. The general enactments, binding upon all, did not infringe upon their political and social idiosyncrasies, but even protected and maintained them; so that each of the nations that constitute the whole, had its own form of constitution. As light illuminates everything—imparting to each object a peculiar vitality—so the Persian Empire extends over a multitude of nations, and leaves to each one its particular character. Some have even kings of their own; each one its distinct language, arms, way of life and customs. All this diversity coexists harmoniously under the impartial dominion of Light ... a combination of peoples—leaving each of them free. Thereby, a stop is put to that barbarism and ferocity with which the nations had been wont to carry on their destructive feuds.[243]

Will Durant, the American historian and philosopher, during one of his speeches, "Persia in the History of Civilization", as an address before the Iran–America Society in Tehran on 21 April 1948, stated:

For thousands of years Persians have been creating beauty. Sixteen centuries before Christ there went from these regions or near it ... You have been here a kind of watershed of civilization, pouring your blood and thought and art and religion eastward and westward into the world ... I need not rehearse for you again the achievements of your Achaemenid period. Then for the first time in known history an empire almost as extensive as the United States received an orderly government, a competence of administration, a web of swift communications, a security of movement by men and goods on majestic roads, equalled before our time only by the zenith of Imperial Rome.[244]

Rulers

| History of Iran | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3200–2700 | |

| Jiroft culture | c. 3100–2200 |

| Lullubi Kingdom/Zamua | c. 3100-675 |

| Elam | 2700–539 |

| Marhaši | c. 2550-2020 |

| Oxus Civilization | c. 2400–1700 |

| Akkadian Empire | 2400–2150 |

| Kassites | c. 1500–1155 |

| Avestan period | c. 1500–500 |

| Neo-Assyrian Empire | 911–609 |

| Urartu | 860–590 |

| Mannaea | 850–616 |

| Zikirti | 750-521 |

| Saparda | 720-670 |