Worm-eating warbler

| Worm-eating warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Helmitheros Rafinesque , 1819

|

| Species: | H. vermivorum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Helmitheros vermivorum (Gmelin, JF, 1789)

| |

| |

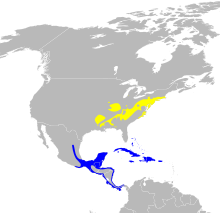

| Range Breeding range Winter range

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Helmitheros vermivorus | |

The worm-eating warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum) is a small New World warbler that breeds in the Eastern United States and migrates to southern Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America for the winter.

Taxonomy

The worm-eating warbler was

Description

The worm-eating warbler is a small

Distribution and habitat

These birds breed in the Eastern United States. Their selected habitats vary significantly between populations.[10] In much of their range, worm-eating warblers are associated with mature hardwood forests on steep slopes. However, recent attention has been focused on coastal breeding populations, as little is known about their ecology or status. Historically, coastal populations would select for pocosin ecosystems. More recently, however, these populations have shifted to frequent use of pine plantations. Current use of pine plantations has resulted in densities higher than in areas previously thought to be their natural habitat. This shift in habitat selection likely demonstrates that worm-eating warblers are more closely associated with shrub structure than stand age or size. If this is the case, the landscape changes that occurred on the Atlantic coastal plain may have had less of an impact on these birds than previously described. Maintaining this species habitat may require managing for dense shrubby midstory and understory. Due to their reliance on shrub structure for foraging, and ground nesting behavior, frequent fires have a negative impact on this species.[11] Other management strategies that reduce the shrub mid-story, increase herbaceous growth, and decrease canopy cover are likely to have a similar effect. More information is needed about their breeding habits in coastal regions as these forests are likely to represent different conditions from their inland counterparts.[12] Fat deposits play a key role in allowing for long distance migration in most passerines. Stopover habitat, or areas that allow birds to replenish their fat stores, are also critical.[13]

In winter, these birds migrate to southern Mexico, the Greater Antilles, and Central America particularly along the Caribbean Slope where they occupy both scrub and moist forests.[14] Worm-eating warblers have disappeared from some parts of their range due to habitat loss but their ability to use both scrub and moist forest ecosystems may be beneficial to the long term conservation of this species.[15]

Behaviour and ecology

Breeding

This bird breeds in dense

Food and feeding

The diet of worm-eating warblers varies across habitat types.

Use of pesticides, especially those broadcast over a wide area, is likely to have an effect on most insectivorous songbird species, including the worm-eating warbler.[18] These pesticides decrease the species' primary food source and could result in long-term toxicity.

References

- . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Helmitheros vermivorum". Avibase.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. pp. 951–952.

- ^ Edwards, George (1760). Gleanings of Natural History, Exhibiting Figures of Quadrupeds, Birds, Insects, Plants &c (in English and French). Vol. 2. London: Printed for the author. pp. 200–202, Plate 305.

- ^ Rafinesque, Constantine Samuel (1819). "Prodrome. De 70 nouveaux Genres d'Animaux découverts dans l'intérieur des États-Unis d'Amérique, durant l'année 1818". Journal de Physique de Chimie et d'Histoire Naturelle et des Arts. 88: 417-429 [418].

- ^ Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2023). "New World warblers, mitrospingid tanagers". IOC World Bird List Version 13.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ISBN 978-84-96553-68-2.

- ^ Pyle, Peter (1997). Identification guide to North American Birds. Bolinas, California: Slate Creek Press. pp. 499–500.

- .

- .

- ^ Pitts, Irvin. "The Status and Breeding Habits of the Worm-eating Warbler in South Carolina" (PDF). Carolinabirdclub.org. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- S2CID 3235707.

- doi:10.2173/bna.367. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- PMID 2798430.

- S2CID 23144697. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- JSTOR 1368770.

- JSTOR 4084999.

External links

- Species account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Species account - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification