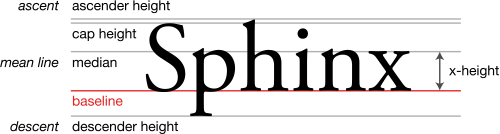

x-height

In typography, the x-height, or corpus size, is the distance between the baseline and the mean line of lowercase letters in a typeface. Typically, this is the height of the letter x in the font (the source of the term), as well as the letters v, w, and z. (Curved letters such as a, c, e, m, n, o, r, s, and u tend to exceed the x-height slightly, due to overshoot; i has a dot that tends to go above x-height.) One of the most important dimensions of a font, x-height defines how high lowercase letters without ascenders are compared to the cap height of uppercase letters.

Display typefaces intended to be used at large sizes, such as on signs and posters, vary in x-height. Many have high x-heights to be read clearly from a distance. This, though, is not universal: some display typefaces such as Cochin and Koch-Antiqua intended for publicity uses have low x-heights, to give them a more elegant, delicate appearance, a mannerism that was particularly common in the early twentieth century.[2][3] Many sans-serif designs that are intended for display text have high x-heights, such as Helvetica or, more extremely, Impact.

Design considerations

Medium x-heights are found on fonts intended for body text, allowing more balance and contrast between upper- and

High x-heights on display typefaces were particularly common in designs in the 1960s and '70s, when

Some research has suggested that while higher x-heights may help with reading smaller text, a very high x-height may be counterproductive, possibly because it becomes harder to identify the shape of a word if every letter is nearly the same height. For the same reason, some sign manuals discourage all-capitals text.[10][11][12]

Use in web design

In

Other important dimensions

Lowercase letters whose height is greater than the x-height either have descenders which extend below the baseline, such as y, g, q, and p, or have ascenders which extend above the x-height, such as l, k, b, and d. The ratio of the x-height to the body height is one of the major characteristics that defines the appearance of a typeface. The height of the capital letters is referred to as cap height. x-height is most important in regular designs, such as most serif and sans-serif designs; script typefaces that mimic irregular handwriting and calligraphy may not have a consistent x-height across all letters.

See also

References

- ^ Vervliet 2008, p. 220; Type Specimen Facsimiles, p. 3

- ^ "Chaparral® Pro release notes" (PDF). Adobe. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Tracy, Walter (1986). "Proportion". Letters of Credit. pp. 48–55.

- ^ "Optical Size". Adobe. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Frere-Jones, Tobias. "MicroPlus". Frere-Jones Type. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Simonson, Mark. "Indiana Jones and the Fonts on the Maps". Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Bierut, Michael. "I Hate ITC Garamond". Design Observer. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Slimbach & Brady. "Adobe Garamond" (PDF). Adobe. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 23, 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ "Introducing Mrs Eaves XL" (PDF). Emigre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Bertucci, Andrew. "Sign Legibility Rules of Thumb" (PDF). United States Sign Council. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Herrman, Ralph (9 April 2012). "Does a large x-height make fonts more legible?". Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Hermann, Ralph (September 2009). "Designing the ultimate wayfinding typeface". Retrieved 22 June 2015.

Notes

- ^ The name "Petit Canon de Garamond is a mistake; it is actually by Robert Granjon.[1]