Typesetting

Typesetting is the composition of

Pre-digital era

Manual typesetting

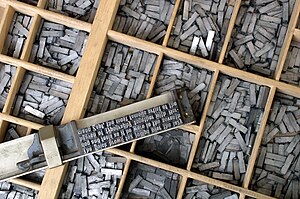

During much of the letterpress era, movable type was composed by hand for each page by workers called compositors. A tray with many dividers, called a case, contained cast metal sorts, each with a single letter or symbol, but backwards (so they would print correctly). The compositor assembled these sorts into words, then lines, then pages of text, which were then bound tightly together by a frame, making up a form or page. If done correctly, all letters were of the same height, and a flat surface of type was created. The form was placed in a press and inked, and then printed (an impression made) on paper.[3] Metal type read backwards, from right to left, and a key skill of the compositor was their ability to read this backwards text.

Before computers were invented, and thus becoming computerized (or digital) typesetting, font sizes were changed by replacing the characters with a different size of type. In letterpress printing, individual letters and punctuation marks were cast on small metal blocks, known as "sorts," and then arranged to form the text for a page. The size of the type was determined by the size of the character on the face of the sort. A compositor would need to physically swap out the sorts for a different size to change the font size.

During typesetting, individual sorts are picked from a type case with the right hand, and set from left to right into a composing stick held in the left hand, appearing to the typesetter as upside down. As seen in the photo of the composing stick, a lower case 'q' looks like a 'd', a lower case 'b' looks like a 'p', a lower case 'p' looks like a 'b' and a lower case 'd' looks like a 'q'. This is reputed to be the origin of the expression "mind your p's and q's". It might just as easily have been "mind your b's and d's".[3]

A forgotten but important part of the process took place after the printing: after cleaning with a solvent the expensive sorts had to be redistributed into the typecase - called sorting or dissing - so they would be ready for reuse. Errors in sorting could later produce misprints if, say, a p was put into the b compartment.

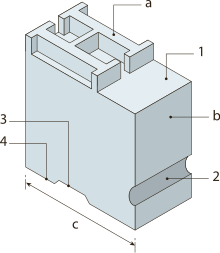

The diagram at right illustrates a cast metal sort: a face, b body or shank, c point size, 1 shoulder, 2 nick, 3 groove, 4 foot. Wooden printing sorts were used for centuries in combination with metal type. Not shown, and more the concern of the casterman, is the "set", or width of each sort. Set width, like body size, is measured in points.

In order to extend the working life of type, and to account for the finite sorts in a case of type, copies of forms were cast when anticipating subsequent printings of a text, freeing the costly type for other work. This was particularly prevalent in book and newspaper work where rotary presses required type forms to wrap an impression cylinder rather than set in the bed of a press. In this process, called

Advances such as the

Hot metal typesetting

The time and effort required to manually compose the text led to several efforts in the 19th century to produce mechanical typesetting. While some, such as the

Phototypesetting

Phototypesetting or "cold type" systems first appeared in the early 1960s and rapidly displaced continuous casting machines. These devices consisted of glass or film disks or strips (one per font) that spun in front of a light source to selectively expose characters onto light-sensitive paper. Originally they were driven by pre-punched paper tapes. Later they were connected to computer front ends.

One of the earliest electronic photocomposition systems was introduced by

Digital era

The next generation of phototypesetting machines to emerge were those that generated characters on a

Computers excel at automatically typesetting and correcting documents.[7] Character-by-character, computer-aided phototypesetting was, in turn, rapidly rendered obsolete in the 1980s by fully digital systems employing a raster image processor to render an entire page to a single high-resolution digital image, now known as imagesetting.

The first commercially successful laser imagesetter, able to make use of a raster image processor, was the Monotype Lasercomp. ECRM, Compugraphic (later purchased by Agfa) and others rapidly followed suit with machines of their own.

Early

.The minicomputer systems output columns of text on film for paste-up and eventually produced entire pages and

.Computerized typesetting was so rare that

In 1985, with the new concept of

By 2000, this industry segment had shrunk because publishers were now capable of integrating typesetting and graphic design on their own in-house computers. Many found the cost of maintaining high standards of typographic design and technical skill made it more economical to outsource to freelancers and graphic design specialists.

The availability of cheap or free fonts made the conversion to do-it-yourself easier, but also opened up a gap between skilled designers and amateurs. The advent of PostScript, supplemented by the

QuarkXPress had enjoyed a market share of 95% in the 1990s, but lost its dominance to Adobe InDesign from the mid-2000s onward.[9]

SCRIPT variants

IBM created and inspired a family of typesetting languages with names that were derivatives of the word "SCRIPT". Later versions of SCRIPT included advanced features, such as automatic generation of a table of contents and index, multicolumn page layout, footnotes, boxes, automatic hyphenation and spelling verification.[10]

NSCRIPT was a port of SCRIPT to OS and TSO from CP-67/CMS SCRIPT.[11]

Waterloo Script was created at the University of Waterloo (UW) later.[12] One version of SCRIPT was created at MIT and the AA/CS at UW took over project development in 1974. The program was first used at UW in 1975. In the 1970s, SCRIPT was the only practical way to word process and format documents using a computer. By the late 1980s, the SCRIPT system had been extended to incorporate various upgrades.[13]

The initial implementation of SCRIPT at UW was documented in the May 1975 issue of the Computing Centre Newsletter, which noted some the advantages of using SCRIPT:

- It easily handles footnotes.

- Page numbers can be in Arabic or Roman numerals, and can appear at the top or bottom of the page, in the centre, on the left or on the right, or on the left for even-numbered pages and on the right for odd-numbered pages.

- Underscoring or overstriking can be made a function of SCRIPT, thus uncomplicating editor functions.

- SCRIPT files are regular OS datasets or CMS files.

- Output can be obtained on the printer, or at the terminal…

The article also pointed out SCRIPT had over 100 commands to assist in formatting documents, though 8 to 10 of these commands were sufficient to complete most formatting jobs. Thus, SCRIPT had many of the capabilities computer users generally associate with contemporary word processors.[14]

DWScript is a version of SCRIPT for MS-DOS, named after its author, D. D. Williams,[15] but was never released to the public and only used internally by IBM.

Script is still available from IBM as part of the

SGML and XML systems

The standard generalized markup language (

XML is a successor of SGML. XSL-FO is most often used to generate PDF files from XML files.

The arrival of SGML/XML as the document model made other typesetting engines popular. Such engines include Datalogics Pager, Penta, Miles 33's OASYS, Xyvision's

YesLogic's

Troff and successors

During the mid-1970s,

TeX and LaTeX

The

, while being an independent typesetting system, can also aid the preparation of TeX documents through its export capability.Other text formatters

GNU

SILE borrows some algorithms from TeX and relies on other libraries such as HarfBuzz and ICU, with an extensible core engine developed in Lua.[17][18] By default, SILE's input documents can be composed in a custom LaTeX-inspired markup (SIL) or in XML. Via the adjunction of 3rd-party modules, composition in Markdown or Djot is also possible.[19]

A new typesetting system Typst tries to combine a simple markup of the input and the possibility of using common programming constructs with a high typographical quality of the output. This system has been in beta testing since March 2023[20][21][22] and was presented in July 2023 at the Tex Users Group (TUG) 2023 conference.[23]

Several other text-formatting software packages exist—notably Lout, Patoline, Pollen, and Ant—but are not widely used.

See also

- Dingbat

- Formula editor

- History of Western typography

- Ligature (typography)

- The Long Short Cut

- Point (typography)

- Prepress

- Printing

- Printing press

- Sort (typesetting)

- Strut (typesetting)

- Symbols – Comprehensive list of typographical symbols

- Technical writing

References

- ^ Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 23 December 2009. Dictionary.reference.com

- ^ Murray, Stuart A., The Library: An Illustrated History, ALA edition, Skyhorse, 2009, page 131

- ^ a b Lyons, M. (2001). Books: A Living History. (pp. 59–61).

- ^ Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology, 1976

- ^ Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology

- ^ Linotype History

- ISSN 1841-7833. 83. Archived from the originalon 2020-04-15. Retrieved 2012-04-09.(webpage has a translation button)

- ^ Helmers, Carl (August 1979). "Notes on the Appearance of BYTE..." BYTE. pp. 158–159.

- ^ "How QuarkXPress became a mere afterthought in publishing". Ars Technica. 2014-01-14. Retrieved 2022-08-07.

- ^ U01-0547, "Introduction to SCRIPT," Archived 2009-06-06 at the Wayback Machine is available through PRTDOC.

- ^ SCRIPT 90.1 Implementation Guide, June 6, 1990

- ^ CSG.uwaterloo.ca

- ^ A Chronology of Computing at The University of Waterloo

- ^ Glossary of University of Waterloo Computing Chronology

- ^ DWScript – Document Composition Facility for the IBM Personal Computer Version 4.6 Updates, DW-04167, Nov 8th, 1985

- ^ IBM Document Composition Facility (DCF)

- ^ "SILE Website". Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ Simon Cozens (2017). "SILE, A new typesetting system" (PDF). TUGboat, Volume 38 (2017), No. 1. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ "Markdown and Djot to PDF with SILE". GitHub. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Typst. A new markup-based typesetting system that is powerful and easy to learn". GitHub. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Typst Website". Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Laurenz Mädje (2022). "Typst. A Programmable Markup Language for typesetting. Master's thesis" (PDF). Technical University Berlin. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Eberhard W. Lisse (2023). "Introduction to Typst" (PDF). TUG 2023 Conference. Retrieved 2023-07-14.