Yoga in advertising

Yoga in advertising is the use of images of modern yoga as exercise to market products of any kind, whether related to yoga or not. Goods sold in this way have included canned beer, fast food and computers.

Yoga is an ancient

The purpose of using yoga in advertising ranges from giving a favourable impression of a product or service, to selling specific yoga-related items like classes, clothing and props. Some such uses, such as of religious symbols like the sacred syllable Om, have been described as cultural appropriation. Yoga advertisements employ themes such as the sexual objectification of women, self-transformation through physical means, and the promise of reduced stress. Images of women in difficult yoga poses feature in advertisements to convey desirable qualities.

Context

Yoga is an ancient meditational spiritual practice from India. Its goal, detachment from the self or kaivalya, was replaced by the self-affirming goals of good health, reduced stress, and physical flexibility.[2] In the early 20th century, it was transformed through Western influences and a process of innovation in India to become an exercise practice.[3] Around the 1960s, modern yoga was transformed further by three global changes: Westerners were able to travel to India, and Indians were able to migrate to the West; people in the West became disillusioned with organised religion, and started to look for alternatives; and yoga became an uncontroversial form of exercise suitable for mass consumption.[4]

Yoga marketing

The growth of yoga as exercise from the 1980s to the 2000s encouraged the market to diversify, first-generation yoga brands such as Iyengar Yoga being joined by second-generation brands such as Anusara Yoga. The scholar of yoga Andrea Jain writes that these were "mass-marketed to the general populace"; successful brands were able to gain audiences of hundreds of thousands from cities around the world.[6] This in turn led to regulation. Professional organisations such as the Yoga Alliance and the European Union of Yoga maintain registries of yoga schools that provide appropriate yoga teacher training, and of yoga teachers who have been trained on approved courses.[7][8] Certifying organisations such as Yoga Alliance have set out guidelines for how their members and others may use their logos in advertisements.[9]

In the Western world, yoga has become "feminized ... both in theory and in practice".

Other uses, for products unrelated to yoga, have been described as ranging from "offensive" to "just plain bizarre", with the Hindu god

The Welsh author

Themes

The

The

A different approach was taken by

-

"Lycra-clad one-legged wheel poses":Eka Pada Urdhva Dhanurasana performed by a Lululemonyoga model

-

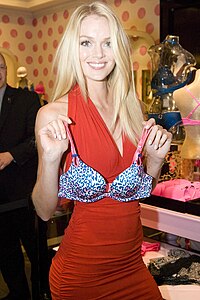

Yoga has been used to sell lingerie. A 2013 campaign featuring Lindsay Ellingson promised women the body of a Victoria's Secret model.[10]

-

Businesses that sell yoga-related products have used Eka Pada Rajakapotasana, as here by Lululemon in 2011

References

- ^ a b Baitmangalkar, Arundhati. "How We Can Work Together to Avoid Cultural Appropriation in Yoga". Yoga International. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- OCLC 290552174.

- .

- OCLC 878953765.

- ^ a b c McLellan, Lea (28 January 2015). "Yoga in Advertising: Taking a Bite of the Yoga Pie". Yoga Basics. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Jain 2015, pp. 73–94 "Branding Yoga".

- ^ Jain 2015, p. 96.

- ^ Mullins, Daya. "Yoga and Yoga Therapy in Germany Today" (PDF). Weg Der Mitte. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Using The Yoga Alliance Professionals Logo". Yoga Alliance. 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ ISBN 9781498528030.

- ^ Hodges, Julie (2007). The Practice of Iyengar Yoga by Mid-Aged Women: An Ancient Tradition in a Modern Life (PDF) (PhD thesis). Newcastle, New South Wales: University of Newcastle. pp. 66–67. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- .

- ^ Lane, Megan (9 October 2003). "The Tyranny of Yoga". BBC News. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Davidson, John (27 May 2014). "Not bending over backwards for a Lenovo ThinkPad Yoga". Financial Review. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Deshpande, Rina (1 May 2019). "What's the Difference Between Cultural Appropriation and Cultural Appreciation?". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b Williams, Holly (29 November 2015). "The great hippie hijack: how consumerism devoured the counterculture dream". The Independent. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

!["Lycra-clad one-legged wheel poses":[16] Eka Pada Urdhva Dhanurasana performed by a Lululemon yoga model](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Lululemon_Yellow_Yoga.jpg/200px-Lululemon_Yellow_Yoga.jpg)