Ansgar the Staller

Ansgar the Staller | |

|---|---|

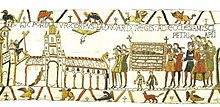

Death of Harold at Hastings, October 1066; | |

| Portreeve of London | |

| In office 1044 (assumed) – 1075 | |

| Monarchs | Edward the Confessor; Harold Godwinson |

| Sheriff of Middlesex | |

| In office 1044 (assumed) – 1075 | |

| Staller, Royal Official | |

| In office ca 1044 – 1066 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | circa 1024-1030 Unknown |

| Died | circa 1085 Normandy |

| Nationality | English |

| Parent | Aethelstan (?-after 1045) |

| Occupation | Anglo-Saxon Royal retainer, landowner, soldier |

| Military service | |

| Commands | London, October-December 1066 |

| Battles/wars | Hastings, Southwark, London Bridge |

Ansgar the Staller or Esegar (c. 1025 – 1085) was one of the wealthiest and most powerful nobles in late Anglo-Saxon England. He escaped badly wounded from the Battle of Hastings in October 1066, then led the defence of London.

His family were of Danish origin and held extensive estates in the Thames Valley, as well as Perivale and Northolt in Middlesex. In 1044, he replaced his father as hereditary Portreeve of London, and Sheriff of Middlesex. Edward the Confessor also made him a Staller, a term of uncertain origin, used for senior officials in his personal household.[1]

Ansgar served Edward throughout his reign, then backed

He successfully repulsed two attacks on London, but when other surviving Anglo-Saxon leaders accepted William as king, he switched sides. However, his power and Danish connections made him dangerous; he was arrested in 1075, his lands distributed to William's supporters. He died in Normandy around 1085.

The Ansgar Freemason Lodge, in Middlesex, founded in 1931, was named after him.[2]

Career

The redistribution of English estates after the

However, his brother Harold Harefoot was appointed regent of England, and in 1037 usurped the throne of England, supported by Leofric of Mercia. Only when he died in 1040 was Harthacnut able to take possession, and after his own death in 1042, his half-brother, Edward the Confessor, became king. As the son of Cnut's Anglo-Saxon predecessor, Æthelred the Unready (966 to 1016), he was backed by Earl Godwin, father of Harold Godwinson, and head of the 'English' faction. This was centred on the old kingdom of Wessex, while London, the economic hub, was dominated by Anglo-Danish supporters of Leofric, including Ansgar's father Athelstan, Portreeve of London, and sheriff of Middlesex.[6]

In early 1044, Athelstan was implicated in a conspiracy against Edward, losing his estate of Waltham Abbey as a result.[7] Edward could not afford to isolate so powerful a family, especially one that shared his dislike of the Godwins;[a] his titles were transferred to Ansgar, who was also appointed 'Staller'. A title used by Edward for his senior household officials, its origin, and exact meaning, is disputed.[8] One suggestion is it derives from comes stabuli, literally Count of the Stable, a title first used by the Byzantine Empire, then adopted by the Franks.[9] Another it is taken from the criteria for becoming a thegn, which required a seat, or steall, and special office in the kings hall. However, this is unproved.[10]

There are few details of Ansgar's life over the next twenty years, but he appears to have served Edward faithfully until his death in January 1066. He was part of a group of powerful nobles who supported Edward, centred in Berkshire, among them Eadnoth, and Bondi, two other stallers.[11] In 1065, he, Bondi, Robert Fitzwymark, and Ralph, appear as witnesses on a charter, in which they are described as Royal stewards.[12]

1066

While Harold was the recognised heir, Edward had been careful to offset his powerful subordinate by promoting factions of Bretons, French, and Normans, many holding positions within Harold's power-base in

Harold's brother Tostig Godwinson, exiled and deprived of his title as Earl of Northumbria in 1065, now asked each of them for their support. Since his former lands in Northumbria were the most suitable for a Norwegian landing, he eventually agreed a deal with Harald. In June, he left his place of exile in Flanders, and raided Harold's estates in southern England, from the Isle of Wight to Sandwich. After making it seem an attack from Normandy was imminent, he then sailed north, while Harold and most of his troops remained in the south.[15]

On 8 September, Tostig arrived in Tynemouth, where he met Harald, who had around 10–15,000 men, on 300 longships.[16] Harold marched north, leaving Ansgar to hold London, and the south; his Danish origins and long-standing dislike of the Godwins meant Harold may not have trusted his reliability in battle. Despite an overwhelming victory at Stamford Bridge on 25 September, William's landing at Pevensey on the 28th forced Harold to return south, where he gathered another army. There is some debate as to whether Ansgar was present at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October; one suggestion is he was badly wounded but escaped capture.[17] Another is that he remained in London.[18]

Despite his victory, William's position remained precarious, and Ansgar played a key role in the councils held by the remaining Anglo-Danish leadership, as they awaited his approach. On 15 October, the 15 year-old

He refused; Guy, Bishop of Amiens, who later attended William's coronation, claimed Ansgar negotiated only as a delaying tactic to improve his defences, although this is unconfirmed.[20] His defence of Southwark in mid-October prevented William entering the city, and forced him to march west, where he secured a crossing at Wallingford. Ansgar repulsed another attack on London Bridge in early December, before Edgar's principal backer, Edwin, Earl of Mercia, switched sides.[21] Edgar submitted to William, who was crowned king in his place on 10 December.[22]

Aftermath

His position hopeless, Ansgar surrendered; he apparently kept his estates, and may have helped suppress a Danish-led revolt in 1069. Despite this, he may have been too powerful for William; he was arrested in 1075, and later transferred to Normandy, where he died around 1085.[18] His property was confiscated, and given to Norman nobles, chiefly Geoffrey Alselin and Geoffrey de Mandeville. Mandeville also took over as Portreeve of London, and Sheriff of Middlesex.[23]

It is suggested East Garston in Berkshire was originally known as "Esgarston", or "Esegar's Estate".[24] In 1931, the Ansgar Freemason Lodge, in Middlesex was named after him, commemorating a hero, who died in the cause of his King, his Country and his Province of Middlesex.[2]

Notes

- ^ Among other things, Edward blamed the Godwins for the death of his brother Arthur, while many resented their rapid rise

References

- ^ Williams 2004.

- ^ a b Ansgar Lodge History.

- ^ Salzman & Page 1959, p. 339.

- ^ Doree 1986, p. 15.

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 420.

- ^ Barlow 2006.

- ^ Brooke, Brooke & Keir 1975, p. 192.

- ^ Hull Domesday Project.

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 1140.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. FN 78.

- ^ Seneca 2001, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. FN80.

- ^ Campbell 1972, p. 154.

- ^ DeVries 2001, pp. 65–67.

- ^ DeVries 1999, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Tjønn 2010, p. 167.

- ^ Bowers 1905, p. 633.

- ^ a b Coe 2017.

- ^ Rex 2011, p. 103.

- ^ Freeman 1869, p. 545.

- ^ Mills 1996, pp. 59–62.

- ^ Rex 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Fleming 1991, p. 113.

- ^ Lewis 2015, p. 197.

Sources

- "Ansgar Lodge History". Ansgar Lodge. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Barlow, Frank (2006). "Edward the Confessor". doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8516. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- Bowers, Robert Woodger (1905). Sketches of Southwark Old and New. W. Wesley and Son.

- Brooke, Christopher; Brooke, Christopher Nugent Lawrence; Keir, Gillian (1975). London, 800-1216: The Shaping of a City. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02686-5.

- Campbell, Miles (1972). "Earl Godwin of Wessex and Edward the Confessor's promise of the throne to William of Normandy". Traditio. 28: 141–158. S2CID 151864893.

- Coe, DF (June 2017). "Asgar the Staller" (PDF). sbwhistory.com. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- DeVries, Kelly (2001). Harold Godwinson in Wales: Military Legitimacy in Late Anglo-Saxon England in The Normans and their Adversaries at War: Essays in Memory of C. Warren Hollister (Warfare in History). Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0851158471.

- ISBN 978-0-85115-763-4.

- Doree, Stephen (1986). Domesday Book and the Origins of Edmonton Hundred. Edmonton Hundred Historical Society.

- Fleming, Robin (1991). Kings and Lords in Conquest England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52694-4.

- Freeman, Edward Augustus (1869). The reign of Harold and the interregnum. 2d ed., rev. 1875. Clarendon Press.

- "Constable, or Staller". Hull Domesday Project. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Kazhdan, A. (1991). "Komes tou Staulou". In ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Lewis, CP (2015). Danish Landowners in Wessex, 1066 in "Danes in Wessex: The Scandinavian Impact on Southern England, c. 800 – c. 1100". Oxbow Press. ISBN 978-1782979319.

- Mills, Peter (1996). "The Battle of London 1066". London Archaeologist. 8 (3).

- Rex, Peter (2011). 1066: A New History of the Norman Conquest. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445608839.

- Salzman, Louis Francis; Page, William (1959). The Victoria History of Oxford. University of London, Institute of Historical Research.

- Seneca, Christine (2001). Keeping up with the Godswinesons; in pursuit of aristocratic status in late Anglo-Saxon England in Anglo-Norman Studies XXIII: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2000". Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0851158259.

- Stenton, Frank M (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford History of England). OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0198217169.

- Tjønn, Halvor (2010). Harald Hardråde (in Norwegian). Saga Bok/Spartacus. ISBN 978-82-430-0558-7.

- Williams, Ann (2004). "Eadnoth the Staller". doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8384. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- Williams, Ann (2008). The World Before Domesday: The English Aristocracy 900-1066. Continuum. ISBN 978-1847252395.