Charles Gavan Duffy

PC | |

|---|---|

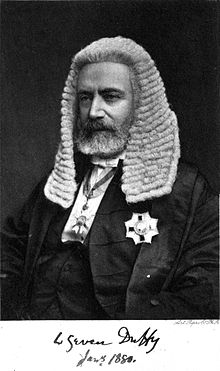

Duffy in 1880 | |

| 8th Premier of Victoria | |

| In office 19 June 1871 – 10 June 1872 | |

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Preceded by | Sir James McCulloch |

| Succeeded by | James Francis |

| 3rd Speaker of the Victorian Legislative Assembly | |

| In office 22 May 1877 – 9 February 1880 | |

| Preceded by | Charles McMahon |

| Succeeded by | Charles McMahon |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 April 1816 British citizenship |

| Spouses |

|

| Profession | Politician |

Sir Charles Gavan Duffy,

Ireland

Early life and career

Duffy was born at No. 10 Dublin Street in

One day, when Duffy was aged 18,

In Belfast, Duffy went on to edit

Duffy was admitted to the

The Nation

In 1842, Duffy co-founded

When he had first followed O'Connell, Duffy concedes that he had "burned with the desire to set up again the

At issue with O'Connell

O'Connell's paper, The Pilot, did not hesitate to identify religion as the "positive and unmistakable" mark of distinction between Irish and English.

In 1845, the

For Duffy there was a further, less liberal basis, for his disaffection: O'Connell's repeated denunciations of a "vile union" in the United States "of republicanism and slavery", and his appeal to Irish Americans to join in the abolitionist struggle.[14] Duffy believed the time was not right "for gratuitous interference in American affairs". Not least because of the desire for American support and funding, it was a common view.[15]

Young Ireland

Following Davis's sudden death in 1845, Duffy appointed John Mitchel deputy editor. Against the background of increasingly violent peasant resistance to evictions and of the onset of famine, Mitchell brought a more militant tone. When the Standard in London observed that the new Irish railways could be used to transport troops to quickly curb agrarian unrest, Mitchel responded that the tracks could be turned into pikes and trains ambushed. O'Connell publicly distanced himself from the seditious import of the remarks—it appeared to some setting Duffy, as the publisher, up for prosecution.[16] When the courts failed to convict, O'Connell pressed the issue, seemingly intent on effecting a break with those he referred to disdainfully as "Young Irelanders"—a reference to Giuseppe Mazzini's anti-clerical and insurrectionist Young Italy.

In 1847, the Repeal Association tabled resolutions declaring that under no circumstances was a nation justified in asserting its liberties by force of arms. The Young Irelanders had not advocated physical force,[17] but in response to the "Peace Resolutions" Thomas Meagher argued that if Repeal could not be carried by moral persuasion and peaceful means, a resort to arms would be a no less honourable course.[18] O'Connell's son John forced the decision: the resolution was carried on the threat of the O'Connells themselves quitting the Association.

Duffy and the other Young Ireland dissidents associated with his paper withdrew and formed themselves as the Irish Confederation.

In the desperate circumstances of the

The League of North and South

On his release, Duffy toured famine-stricken Ireland with the renowned Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher

In 1842, he had already allied himself with

In 1850, a convention called in Dublin by Duffy and MacKnight formed the Irish

Uniting activists across the sectarian and constitutional divide, in 1852, the League helped return Duffy (for New Ross) and 49 other tenant-rights MPs to Westminster.[25] In November 1852, Lord Derby's short-lived Conservative government introduced a land bill to compensate Irish tenants on eviction for improvements they had made to the land. The bill passed in the House of Commons in 1853 and 1854, but failed to win consent of the landed grandees in the House of Lords.[26]

What Duffy optimistically hailed as the "League of North and South" unravelled. In the Catholic South, Archbishop Cullen approved the leading Catholic MPs William Keogh and John Sadleir breaking their pledge of independent opposition and accepting positions in a new Whig administration.[27][28] In the Protestant North William Sharman Crawford and other League candidates had their meetings broken up by Orange "bludgeon men".[29]

An "Irish Mazzini"

To the cause of tenant rights, Cullen was sympathetic,

Until O'Connell's death, Duffy suggested that Rome had "believed in the possibility of an Independent Catholic State" in Ireland, but that since O'Connell's death could "only see the possibility of a Red Republic". The Curia had, as a result, returned to "her design of treating Ireland as an entrenched camp of Catholicity in the heart of the British Empire, capable of leavening the whole." Ireland for this purpose had to be"thoroughly imperialised, loyalised, welded into England."[31]

Cullen has been described as the man who "borrowed the British Empire." Under his leadership the Irish church developed an "Hiberno-Roman" mission that was ultimately extended through Britain to the entire English-speaking world.[32] But Cullen's biographers would argue that Duffy travestied Cullen and his church's complex and nuanced relationship to Irish nationalism.[33][34]—perhaps as much as Cullen caricatured Duffy's separatism.

Australia

Emigration and new political career

The cause of the Irish tenants, and indeed of Ireland generally, seemed to Duffy more hopeless than ever. Broken in health and spirit, he published in 1855 a farewell address to his constituency, declaring that he had resolved to retire from parliament, as it was no longer possible to accomplish the task for which he had solicited their votes.[35] To John Dillon he wrote that an Ireland where McKeogh typified patriotism and Cullen the church was an Ireland in which he could no longer live.[36]

In 1856, Duffy and his family emigrated to Australia. After being feted in Sydney and Melbourne, he settled in the newly formed Colony of Victoria.[37] Duffy was followed to Melbourne by Margaret Callan. Her daughter was later to marry Duffy's eldest son by his first marriage, John Gavan Duffy.

Duffy initially practised law in Melbourne, but a public appeal was soon held to enable him to buy the freehold property necessary to stand for the colonial

Duffy's Land Act

Duffy stood on a platform of land reform. With the collapse of the

Duffy's Land Act was passed in 1862. Like the Nicholson Act of 1860 which it modified, the Duffy Act provided, in specified areas, for new and extended pastoral leases. It was an effort to break the land-holding monopoly of the so-called "squatter" class. However, the bill had been amended into ineffectiveness by the Legislative Council so that it was easy for the squatters to employ dummies and extend their control. Duffy's attempts to correct the legislation were defeated. Historian Don Garden commented that "Unfortunately Duffy's dreams were on a higher plane than his practical skills as a legislator and the morals of those opposed to him."[40]

In 1858–59, Melbourne Punch cartoons linked Duffy and O'Shanassy with images of the French Revolution to undermine their Ministry. One famous Punch image, "Citizens John and Charles", depicted the pair as French revolutionaries holding the skull and cross bone flag of the so-called Victorian Republic.[41] The O'Shanassy Ministry was defeated at the 1859 election and a new government formed.

Premier of Victoria

In 1871, Duffy led the opposition to Premier

An

Speakership and retirement

When Berry became Premier in 1877 he made Duffy Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, a post he held without much enthusiasm until handing it over to Peter Lalor, the younger brother of James Fintan Lalor, in 1880. Thereafter he quit politics and retired to southern France where he wrote his memoirs: The League of North and South, 1850–54 (1886) and My Life in Two Hemispheres (1898).

In exile in France, Duffy was an enthusiastic supporter of the

In recognition of his services to Victoria, he was knighted in 1873 and made KCMG in 1877. He married for a third time in Paris in 1881, to Louise Hall, and they had four more children.[26]

Marriages and children

In 1842, Duffy married Emily McLaughlin (1820–1845), with whom he had two children, one of whom survived, his son John Gavan Duffy. Emily died in 1845. In 1846 he married his cousin from Newry, Susan Hughes (1827–1878), with whom he had eight children, six of whom survived. After Susan died in 1878, he married for a third time, in Paris in 1881, to Louise Hall (1858–1889)[43][26] by whom had two further children.

Of his eight surviving children:

- John Gavan Duffy (1844–1917) was a Victorian politician who served variously as Minister for Agriculture, Attorney-General, and Postmaster-General.[44]

- Sir Frank Gavan Duffy (1852–1936), was Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia 1931–35.[45]

- Sir Charles Cashel Gavan Duffy (1855-1932) was clerk of the Australian House of Representatives in 1901-17 and of the Senate in 1917-20.[46]

- Philip Cormac Gavan Duffy (1862–1954), a surveyor and civil engineer noted for his work in Western Australia on the Coolgardie water supply,[46]

- Louise Gavan Duffy (1884–1969) was the joint secretary of the nationalist women's organization, Cumann na mBan, and was an Irish republican present at the 1916 Easter Rising and an Irish language enthusiast who founded an Irish language school, Scoil Bhride (St Bridget)'s Girls School in Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin.[47]

- Roman Catholic Church in Ireland a "special position".[48]

A grandson, Sir Charles Leonard Gavan Duffy, was a judge on the Supreme Court of Victoria, Australia.[49]

Death

Sir Charles Gavan Duffy died in Nice, France in 1903, aged 86.[26]

He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.

Works

Notes

- ^ "Birthplace of Charles Gavin Duffy, Dublin Street, ROOSKY, Monaghan, MONAGHAN". Buildings of Ireland. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ The Northern Standard, Monaghan, p. 1, Thursday, 14 January 2021.

- ^ Ó Cathaoir., Breandán (7 February 2003). "An Irishman's Diary". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- hdl:2027/hvd.hwke3w. Archivedfrom the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Duffy, Charles Gavan (1845). The Ballad Poetry of Ireland. Duffy's library of Ireland. Dublin: J. Duffy. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ Young Ireland, T.F. O'Sullivan, The Kerryman Ltd. 1945, p. 6

- ^ Moody, p 38.

- ^ Bardon, Jonathan (2008). A History of Ireland in 250 Episodes. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. p. 367.

- ISBN 0571092675.

- ISBN 9780415127769.

- ^ O'Connell to Cullen, 9 May 1842. Maurice O'Connell (ed.) The Correspondence of Daniel O'Connell. Shannon: Irish University Press, 8 vols.), vol. vii, p. 158

- ISBN 9781856355964.

- ISBN 0813213037. Archivedfrom the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Jenkins, Lee (Autumn 1999). "Beyond the Pale: Frederick Douglass in Cork" (PDF). The Irish Review (24): 92. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Kinealy, Christine (August 2011). "The Irish Abolitionist: Daniel O'Connell". irishamerica.com. Irish America. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ McCullagh, John (8 November 2010). "Irish Confederation formed". newryjournal.co.uk/. Newry Journal. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Doheny, Michael (1951). The Felon's Track. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son. p. 105

- ^ O'Sullivan, T. F. (1945). Young Ireland. The Kerryman Ltd. pp. 195–6

- ^ Object, Object. "Terence LaRocca (1974) "The Irish Career of Charles Gavan Duffy 1840–1855", Doctoral Dissertation, Loyola University Chicago, p. 3. Loyola eCommons" (PDF). Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Duffy, Charles Gavan (1898). My life in two hemispheres, Volume 1. London: Fischer Unwin. p. 16. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(Oxford University Press, 2004)

- ^ Smith, G.B., 'Godkin, James (1806–1879)', rev. C. A. Creffield, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004)

- ^ "MacKnight (McKnight), James | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Lyons, Dr Jane (1 March 2013). "Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, My Life in Two Hemispheres, Vol. II". From-Ireland.net. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Duffy, Charles Gavan (1886). The League of North and South. London: Chapman & Hall.

- ^ doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32921. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ISBN 9780813208961. Archivedfrom the original on 2 April 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ See also Whyte, John Henry (1958). The Independent Irish Party 1850-9. Oxford University Press. p. 139.

- ISBN 9780198205555. Archivedfrom the original on 2 April 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Barr, Colin. "Cullen, Paul". cambridge.org. Dictionary of Irish Biography. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ a b Good, James Winder (1920). Irish Unionism. London: Fischer Unwin. p. 113.

- .

- S2CID 156595729.

- ISBN 9781846822353

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: O'Brien, Richard Barry (1912). "Duffy, Charles Gavan". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: O'Brien, Richard Barry (1912). "Duffy, Charles Gavan". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Duffy to John Dillon, April 1855, Gavan Duffy Papers, National Library of Ireland

- ^ Dictionary of Irish National Biography

- ^ "THE USAGES OF THE IMPERIAL PARLIAMENT". Melbourne Punch. 4 December 1856. p. 5. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ McCaughey, Victoria's Colonial Governors, p. 75

- ^ George Gavan Duffy papers Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, historyireland.com; accessed 6 March 2016.

- ^ Punch, 7 January 1859, p. 5

- ^ D.J. O'Hearn, Erin go bragh – Advance Australia Fair: a hundred years of growing, Melbourne: Celtic Club, 1990, p. 67.

- ^ "Charles Gavan Duffy Family Tree". www.ancestry.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Duffy, John Gavan". Parliament of Victoria. 1985. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32921. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ a b "Former Member Profile - Sir Charles Gavan Duffy". www.parliament.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52592. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ Irish Law Times Report vol. 86 (1952), pp. 49–73.

- ^ Francis, Charles (1981). "Duffy, Sir Charles Leonard Gavan (1882–1961)". Biography – Sir Charles Leonard Gavan Duffy. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Review: My Life in Two Hemispheres by Charles Gavan Duffy". The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. 85: 209–210. 12 February 1898. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

References

- Browne, Geoff, A Biographical Register of the Victorian Parliament, 1900–84, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1985.

- Duffy, Charles Gavan. Four Years of Irish History 1845–1849, Robertson, Melbourne, 1883. (autobiography and recollections)

- Garden, Don. Victoria: A History, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1984.

- Keatinge, Patrick, 'The Formative Years of the Irish Diplomatic Service', Éire-Ireland, 6, 3 (Autumn 1971), pp. 57–71.

- McCarthy, Justin. History of Our Own Times, Vols 1–4, 1895.

- McCaughey, Davis. et al. Victoria's Colonial Governors 1839–1900, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1993.

- O'Brien, Antony. Shenanigans on the Ovens Goldfields: the 1859 election, Artillery Publishing, Hartwell, 2005, (p. xi & Ch.2)

- Thompson, Kathleen and Serle, Geoffrey. A Biographical Register of the Victorian Parliament, 1856–1900, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1972.

- Wright, Raymond. A People's Counsel. A History of the Parliament of Victoria, 1856–1990, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992.

Further reading

- The Politics of Irish Literature: from Thomas Davis to W.B. Yeats, Malcolm Brown, Allen & Unwin, 1973.

- John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many, Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press.

- Thomas Davis, The Thinker and Teacher, Arthur Griffith, M.H. Gill & Son 1922.

- Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher His Political and Military Career, Capt. W. F. Lyons, Burns Oates & Washbourne Limited 1869

- Young Ireland and 1848, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1949.

- Daniel O'Connell The Irish Liberator, Dennis Gwynn, Hutchinson & Co, Ltd.

- O'Connell Davis and the Colleges Bill, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1948.

- Smith O'Brien And The "Secession", Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press

- Meagher of The Sword, Edited By Arthur Griffith, M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd. 1916.

- Young Irelander Abroad The Diary of Charles Hart, Edited by Brendan O'Cathaoir, University Press.

- John Mitchel First Felon for Ireland, Edited By Brian O'Higgins, Brian O'Higgins 1947.

- Rossa's Recollections 1838 to 1898, Intro by Sean O'Luing, The Lyons Press 2004.

- Labour in Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1910.

- The Re-Conquest of Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1915.

- John Mitchel Noted Irish Lives, Louis J. Walsh, The Talbot Press Ltd 1934.

- Thomas Davis: Essays and Poems, Centenary Memoir, M. H Gill, M.H. Gill & Son, Ltd MCMXLV.

- Life of John Martin, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy & Co., Ltd 1901.

- Life of John Mitchel, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy and Co., Ltd 1908.

- John Mitchel, P. S. O'Hegarty, Maunsel & Company, Ltd 1917.

- The Fenians in Context Irish Politics & Society 1848–82, R. V. Comerford, Wolfhound Press 1998

- William Smith O'Brien and the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848, Robert Sloan, Four Courts Press 2000

- Irish Mitchel, Seamus MacCall, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd 1938.

- Ireland Her Own, T. A. Jackson, Lawrence & Wishart Ltd 1976.

- Life and Times of Daniel O'Connell, T. C. Luby, Cameron & Ferguson.

- Young Ireland, T. F. O'Sullivan, The Kerryman Ltd. 1945.

- Irish Rebel John Devoy and America's Fight for Irish Freedom, Terry Golway, St. Martin's Griffin 1998.

- Paddy's Lament Ireland 1846–1847 Prelude to Hatred, Thomas Gallagher, Poolbeg 1994.

- The Great Shame, Thomas Keneally, Anchor Books 1999.

- James Fintan Lalor, Thomas, P. O'Neill, Golden Publications 2003.

- Charles Gavan Duffy: Conversations With Carlyle (1892), with Introduction, Stray Thoughts on Young Ireland, by Brendan Clifford, Athol Books, Belfast, ISBN 0850341140. (Pg. 32 Titled, Foster's account of Young Ireland.)

- Envoi, Taking Leave of Roy Foster, by Brendan Clifford and Julianne Herlihy, Aubane Historical Society, Cork.

- The Falcon Family, or, Young Ireland, by M. W. Savage, London, 1845. (An Gorta Mor)Quinnipiac University

External links

Media related to Charles Gavan Duffy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles Gavan Duffy at Wikimedia Commons Works related to Charles Gavan Duffy at Wikisource

Works related to Charles Gavan Duffy at Wikisource- Works by Charles Gavan Duffy at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Gavan Duffy at the Internet Archive

- Poetry of Ireland, with references to Duffy

- Early Life in Monaghan by Charles Gavan Duffy