Dinheirosaurus

| Dinheirosaurus Temporal range:

Late Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd to 9th dorsal vertebrae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Diplodocoidea |

| Family: | †Diplodocidae |

| Genus: | †Dinheirosaurus Bonaparte & Mateus, 1999 |

| Species: | †D. lourinhanensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis Bonaparte & Mateus, 1999

| |

Dinheirosaurus is a

The known material includes two

Dinheirosaurus is a diplodocid, a relative of Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Barosaurus, Supersaurus, and Tornieria. Among those, the closest relative to Dinheirosaurus is Supersaurus.

Discovery and naming

ML 414 was first uncovered in 1987 by Mr. Carlos Anunciação. He was associated with the Museu da Lourinhã, and after the excavations which lasted from the time of discovery until 1992,[2] the specimen was then moved into the museum, and catalogued under the number 414.[3] Dantas et al. preliminarily announced ML 414 as soon as the excavations were complete. To remove the fossils from the surrounding rock, a bulldozer and tilt hammer were needed. The fossils were situated at the top of a coastal cliff, and once removed, were shipped to Lourinhã in two blocks with the help of a crane. A year before being described as a new taxon, Dantas et al. assigned ML 414 to Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis, previously grouped under Apatosaurus. José Bonaparte and Octávio Mateus studied the material of Lourinhasaurus, concluding one specimen, under the name ML 414, to be more closely related to diplodocids of the Morrison Formation, and thus warranting a new binomial name. This new species was described as Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis, with a full meaning of "Porto Dinheiro lizard from Lourinhã".[2][3]

Dinheirosaurus material included

Description

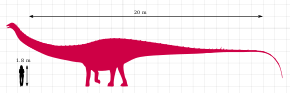

Dinheirosaurus was an average sized diplodocid, and had an elongated neck and tail.[4] The main features of the genus are based on its vertebral anatomy, and multiple vertebrae from across the spine have been found.[2] In total, Dinheirosaurus would have had an approximate length of 20–25 metres (66–82 ft) and weighed 8.8 metric tons (9.7 short tons).[6][7][8]

The animal is not known well from non-vertebral material, currently only consisting of partial ribs and a fragment of a pelvis. One of the ribs attached to the cervicals, and is quite fragmentary. It is elongated, although that might be a feature of distortion. Also undescribed by Bonaparte & Mateus are a set of thoracic ribs. Two ribs are from the left side of the animal. They are T-shaped in cross section, and display plesiomorphic features, although their incomplete state makes their identification uncertain. Multiple right ribs are preserved, including both the shafts and heads. They are similar to the left ribs, which also show that they lack pneumtization.[3] Other appendicular (non-vertebral) material includes a very incomplete and fragmentary shaft of the pubis, and over one hundred gastroliths. The pubis displays practically no anatomical features, and the gastroliths were not described in detail by Mannion et al. in 2012.[3]

Vertebrae

The most distinguishing material of Dinheirosaurus comes from the vertebrae, which are well represented and described. Of the cervicals, only two of the assumed fifteen are preserved. According to Bonaparte & Mateus (1999), the cervicals would number 13 and 14. Apparently cervical 15 was lost during the excavation and removal of the holotype and only specimen of Dinheirosaurus. As of the original description, the thirteenth cervical was only prepared on the lateroventral portion. The length of the centrum is 71 cm (28 in), and the fourteenth cervical is quite similar overall. 63 cm (25 in) is the total measurement of the 14th cervical's centrum, which is well-preserved, complete, and concave along the bottom edge. The

A relatively complete series of dorsal vertebrae are known, which number one to seven. All of the dorsals, however, are distorted upwards due to their state of preservation. Bonaparte & Mateus (1999) noted that the position of the dorsals was not certain, and that in fact the first dorsal could have been the last cervical or even the second dorsal. A similar numbering was found in Diplodocus, with the first and second dorsals similar in anatomy to the last and second-last cervical. The dorsal vary in length from the 58 cm (23 in) of the first dorsal to the 25 cm (9.8 in) of the seventh, eight and ninth dorsals. Height in the vertebrae is also quite variable, with the shortest height being 51 cm (20 in) tall to 76 cm (30 in) tall, increasing from the first dorsal.[2]

Classification

Dinheirosaurus is not extremely well known, and as a consequence, its

| Diplodocidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Previously, Dinheirosaurus was classified within a Diplodocidae excluding Apatosaurus, for the differences anatomically are quite great. Bonaparte & Mateus found that a few features present suggested that Dinheirosaurus was more derived than Diplodocus, but

Paleobiology

As a diplodocid, it is probable that Dinheirosaurus possessed a whip-tail. If it did, it has been speculated that its tail could have been used like a bullwhip, with supersonic speed[11] or, more recently, as a tactile organ to keep in touch with other members of a group.[12] Being related to both Apatosaurus and Diplodocus, Dinheirosaurus probably possessed a squared snout. This means that it was probably a non-selective ground-feeding sauropod.[13]

Digestion

Dinheirosaurus is one of relatively few sauropods for which gastroliths were found obviously alongside the type specimen. In 2007, an experiment using Dinheirosaurus, Diplodocus (=Seismosaurus), and

Paleoecology

Dinheirosaurus was one of many dinosaurs to have lived in the

Biogeography

Many eusauropods, including Dinheirosaurus have been found in the Late Jurassic of Europe. The sauropods are from around the base of the Tithonian as based on the presence of Anchispirocyclina lusitanica. One sauropod, a diplodocid currently based on an unnamed specimen including vertebrae and some bones, is clearly different from Dinheirosaurus and Losillasaurus, confirming the presence of a least two and possibly more diplodocids in the Late Jurassic of Spain and Portugal. This is unique in the variety of diplodocoids in all Europe, with the only other genera possibly non-diplodocoid (Cetiosauriscus), or classified in Rebbachisauridae. This suggests that the biogeography of primitive sauropods is incomplete, with possible primitive eusauropods and diplodocids surviving in the Late Jurassic, potentially until the Berriasian.[5]

References

- ^ PMID 25870766.

- ^ ISSN 0524-9511. Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 September 2007.

- ^ S2CID 56468989.

- ^ OCLC 801843269.

- ^ ISSN 0213-683X. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Mateus, O. (2010). "Paleontological Collections of the Museum of Lourinhã (Portugal)" (PDF). In Brandao, J.M.; Callapez, P.M.; Mateus, O.; et al. (eds.). Colecções e museus de Geologia: missão e gestão. Universidade de Coimbra e Centro de Estudos e Filosofia da História da Ciência Coimbra. pp. 121–126.

- ^ Mateus, O. (2009). "THE SAUROPOD DINOSAUR TURIASAURUS RIODEVENSIS IN THE LATE JURASSIC OF PORTUGAL" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- Bibcode:2020dffs.book.....M.

- PMID 24828328.

- S2CID 54817543.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 83696153.

- S2CID 219762797.

- PMID 21494685.

- PMID 17254987.

- ^ PMID 24869965.

- ^ Mateus, O.; Walen, A.; Antunes, M.T. (2006). "The large theropod fauna of the Lourinhã Formation (Portugal) and its similarity to the Morrison Formation, with a description of a new species of Allosaurus" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 36: 123–129.

- ^ PMID 24598585.

- ^ S2CID 59387149.

- .

- ^ Ruiz-Omeñaca, J.I.; Canudo, J.I. (2004). "Dinosaurios ornitópodos del Cretácico inferior de la Península Ibérica". Geo-Temas. 6 (5): 63–65.

- ^ a b Thulborn, R.A. (1973). "Teeth of ornithischian dinosaurs from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal, with description of a hypsilophodontid (Phyllodon henkeli gen. et sp. nov.) from the Guimarota lignite". Contribuição para o conhecimento da Fauna do Kimerridgiano da Mina de Lignito Guimarota (Leiria, Portugal). Vol. 22. Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Memória (Nova Série). pp. 89–134.

- PMID 19324778.

- S2CID 10930309.

- .

- .

- .