Gallic rooster

The Gallic rooster (

France

During the times of Ancient Rome,

Its association with France dates back from the

The popularity of the Gallic rooster as a national personification faded away until its resurgence during the French Revolution (1789). The republican historiography completely modified the traditional perception of the origins of France. Until then, the royal historiography dated the origins of France back to the baptism of Clovis I in 496, the "first Christian king of France". The republicans rejected this royalist and Christian origin of the country and trace the origins of France back to the ancient Gaul. Although purely apocryphal, the rooster became the personification of the early inhabitants of France, the Gauls.

The Gallic rooster, colloquially named

Today, it is often used as a national

The popularity of the symbol extends into business through several notable brands:

- French tricolouras its logo,

- the logo of Pathé, a French-born, now international company of film production and distribution,

- Ayam Brand, an Asia-wide food company based in Singapore founded by a Frenchman in 1892 formerly known as "A. Clouet & Co.", the name came from the Malay word ayam meaning "chicken" in reference to the rooster adorning many of the Clouet products at the time.[4]

Another heraldic animal officially used by the French nation was the

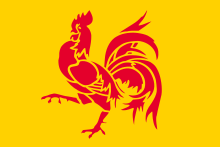

Wallonia

The Gallic rooster was adopted as the symbol of

Cocorico

In France, the

See also

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-140-45516-8.

- ISBN 978-0195089615.

- ^ Caesar, Julius. . Commentarii de Bello Gallico [Commentaries on the Gallic War]. Vol. Book 6. Translated from Latin by William Alexander McDevitte and W. S. Bohn (1869) – via Wikisource.

- ^ "How a symbol of France ended up on the cans of Asia's Ayam Brand". South China Morning Post. 30 June 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "The symbols of Empire". Fondation Napoléon. June 2004. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

External links

- French presidency - symbols of the French Republic

- Embassy of France in the United States - additional information

- French Prime Minister's office - additional information Archived 7 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Images of Footix, the cockerel mascot of the 1998 FIFA World Cup.

- France plucks its bird from peril, from BBC. A plan to preserve the genetic heritage of the French cockerel.

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (July 2010) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|