Granulite

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2012) |

Granulites are a class of high-grade

The minerals present in a granulite will vary depending on the parent rock of the granulite and the temperature and pressure conditions experienced during metamorphism. A common type of granulite found in high-grade metamorphic rocks of the continents contains

A granulite may be visually quite distinct with abundant small pink or red pyralspite garnets in a 'granular'

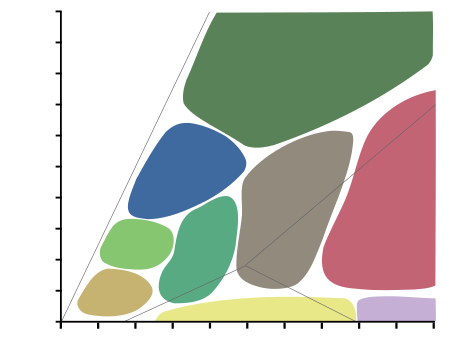

banding.| Diagram showing metamorphic facies in upper mantle .

|

Formation

Granulites form at crustal depths, typically during regional metamorphism at high thermal gradients of greater than 30 °C/km.[2] In continental crustal rocks, biotite may break down at high temperatures to form orthopyroxene + potassium feldspar + water, producing a granulite. Other possible minerals formed at dehydration melting conditions include sapphirine, spinel, sillimanite, and osumilite. Some assemblages such as sapphirine + quartz indicate very high temperatures of greater than 900 °C. Some granulites may represent the residues of partial melting at extraction of felsic melts in variable amounts, and in extreme cases represent rocks that all constituent minerals are anhydrous and thus look as if they did not melt at ultrahigh temperature conditions. Therefore, very high temperatures of 900 to 1150 °C are even necessary to produce the granulite-facies mineral assemblages. Such high temperatures at crustal depths only can be delivered by upwelling of the asthenospheric mantle in continental rifting settings, which can cause the regional metamorphism at the high thermal gradients of greater than 30 °C/km.

Granulite facies

The granulite facies is determined by the lower temperature boundary of 700 ± 50 °C and the pressure range of 2–15 kb. The most common mineral assemblage of granulite facies consists of antiperthitic plagioclase, alkali feldspar containing up to 50% albite and Al2O3-rich pyroxenes.

Transition between amphibolite and granulite facies is defined by these reaction isograds:

- amphibole → pyroxene + H2O

- biotite → K-feldspar + garnet + orthopyroxene + H2O.

Hornblende granulite subfacies is a transitional coexistence region of anhydrous and hydrated ferromagnesian minerals, so the above-mentioned isograds mark the boundary with pyroxene granulite subfacies – facies with completely anhydrous mineral assemblages.[1]

1911 Encyclopædia Britannica definition

Granulite (Latin granulum, "a little grain") is a name used by petrographers to designate two distinct classes of rocks. According to the terminology of the French school it signifies a granite in which both kinds of mica (muscovite and biotite) occur, and corresponds to the German Granit, or to the English muscovite biotite granite. This application has not been accepted generally. [This granitic meaning of granulite is now obsolete.][3] To the German petrologists granulite means a more or less banded fine-grained metamorphic rock, consisting mainly of quartz and feldspar in very small irregular crystals and usually also containing a fair number of minute, rounded, pale-red garnets. Among English and American geologists the term is generally employed in this sense.[4]

The granulites are very closely allied to the gneisses, as they consist of nearly the same minerals, but they are finer-grained, have usually less perfect foliation, are more frequently garnetiferous, and have some special features of microscopic structure. In the rocks of this group the minerals, as seen in a microscopic slide, occur as small rounded grains forming a closely fitted mosaic. The individual crystals never have perfect form, and indeed traces of it are rare. In some granulites they interlock, with irregular borders; in others they have been drawn out and flattened into tapering lenticles by crushing. In most cases they are somewhat rounded with smaller grains between the larger. This is especially true of the quartz and feldspar which are the predominant minerals; mica always appears as flat scales (irregular or rounded but not hexagonal). Both muscovite and biotite may be present and vary considerably in abundance; very commonly they have their flat sides parallel and give the rock a rudimentary schistosity, and they may be aggregated into bands in which case the granulites are indistinguishable from certain varieties of gneiss. The garnets are very generally larger than the above-mentioned ingredients, and easily visible with the eye as pink spots on the broken surfaces of the rock. They usually are filled with enclosed grains of the other minerals.[4]

The feldspar of the granulites is mostly

orthite and tourmaline. Though occasionally we may find larger grains of feldspar, quartz or epidote, it is more characteristic of these rocks that all the minerals are in small, nearly uniform, imperfectly shaped individuals.[4]On account of the minuteness with which it has been described and the important controversies on points of theoretical geology which have arisen regarding it, the granulite district of

intrusive masses which may be nearly massive or may have gneissose, flaser or granulitic structures. These have been developed largely by the injection of semi-consolidated highly viscous intrusions, and the varieties of texture are original or were produced very shortly after the crystallization of the rocks. Meanwhile, however, Lehmanns advocacy of post-consolidation crushing as a factor in the development of granulites has been so successful that the terms granulitization and granulitic structures are widely employed to indicate the results of dynamometamorphism acting on rocks at a period long after their solidification.[4]The Saxon granulites are apparently for the most part igneous and correspond in composition to granites and porphyries. There are, however, many granulites which undoubtedly were originally sediments (arkoses, grits and sandstones). A large part of the highlands of Scotland consists of paragranulites of this kind, which have received the group name of Moine gneisses.[4]

Along with the typical

serpentine, but the exact conditions under which they are formed and the significance of their structures is not very clearly understood.[4]

See also

- Metamorphic facies

- Metamorphic rocks

- Migmatite and granite origin

- Ultrahigh-temperature metamorphism

References

- ^ ISBN 0-442-20623-2

- ^ Zheng, Y.-F., Chen, R.-X., 2017. Regional metamorphism at extreme conditions: Implications for orogeny at convergent plate margins. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 145, 46-73.

- ^ "Carnets géologique de Philippe Glangeaud – Glossaire" (in French). Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Flett, John Smith (1911). "Granulite". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 360–361.

External links

Media related to Granulite at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Granulite at Wikimedia Commons