Diorite

Diorite (

Diorite is found in mountain-building belts (

Diorite has been used since prehistoric times as decorative stone. It was used by the Akkadian Empire of Sargon of Akkad for funerary sculptures, and by many later civilizations for sculptures and building stone.

Description

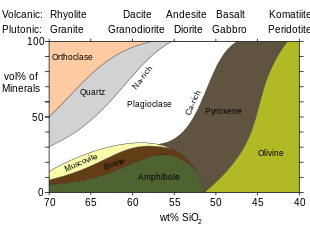

Diorite is an intrusive igneous rock composed principally of the silicate minerals plagioclase feldspar (typically andesine), biotite, hornblende, and sometimes pyroxene. The chemical composition of diorite is intermediate, between that of mafic gabbro and felsic granite.[3][4] It is distinguished from gabbro on the basis of the composition of the plagioclase species; the plagioclase in diorite is richer in sodium and poorer in calcium.[5][6][7]

Geologists use rigorous quantitative definitions to classify coarse-grained igneous rocks, based on the mineral content of the rock. For igneous rocks composed mostly of silicate minerals, and in which at least 10% of the mineral content consists of

The composition of the plagioclase cannot easily be determined

Dioritoids form a family of rock types similar to diorite, such as monzodiorite, quartz diorite, or nepheline-bearing diorite. Diorite itself is more narrowly defined, as a dioritoid in which quartz makes up less than 5% of the QAPF content, feldspathoids are not present, and plagioclase makes up more than 90% of the feldspar content.[11][5][6]

Diorite may contain small amounts of quartz, microcline, and olivine. Zircon, apatite, titanite, magnetite, ilmenite, and sulfides occur as accessory minerals.[12] Varieties deficient in hornblende and other dark minerals are called leucodiorite.[6][13] A ferrodiorite is a dioritoid enriched in iron[14] and titanium. Ferrodiorites are common in the lower oceanic crust.[15]

Coarse-grained (

Occurrence

Diorite results from the

Diorite source localities include

An orbicular variety found in Corsica was formerly called corsite.[33] An obsolete name for microdiorite, markfieldite, was given by Frederick Henry Hatch in 1909 to exposures near the village of Markfield, England.[34]

Use

Human use of diorite dates at least to the

The first great

Diorite was used by the

Today, diorite is uncommon in construction, although it shares similar physical properties with granite. Diorite is often sold commercially as "black granite".[44] Diorite's modern uses include construction aggregate, curbing, usage as dimension stones, cobblestone, and facing stones.

-

Naqada II jar with lug handles; c. 3500–3050 BC; height: 13 cm (5 in); Los Angeles County Museum of Art(US)

-

Neo-Sumerian period); height: 46 cm (20 in), width: 33 cm (10 in), depth: 22.5 cm (8.9 in); Louvre

-

Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin, Germany)

-

Head of a cow goddess (Mehet-Weret); 1390-1352 BC; height: 53.6 cm (21.1 in), width: 28 cm (11 in), depth: 33 cm (13 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art(New York City)

-

Statue of Amun; 1336-1327 BC; height: 220 cm (87 in), width: 44[clarification needed], length: 78 cm (31 in); Louvre

-

Block statue of the god's father Pameniuwedja, son of Nesmin and Nestefnut; 4th century BC; height: 34.6 cm (13.6 in), width: 14.5 cm (5.7 in), depth: 19.1 cm (7.5 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Vase withgilt bronzeornaments; c. 1780; 61 cm × 40.6 cm (24.0 in × 16.0 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Palazzo delle Poste, Naples, Italy, Gino Franzi, 1936. Modernism, constructed with marble and diorite.

See also

References

- ^ "diorite". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ "diorite". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ISBN 0716724383.

- ^ ISBN 0922152349.

- ^ S2CID 28548230.

- ^ a b c d e "Rock Classification Scheme – Vol 1 – Igneous" (PDF). British Geological Survey: Rock Classification Scheme. 1: 1–52. 1999.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-88006-0.

- ^ Jackson 1997, "dioritoid".

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 71.

- ^ "diorite". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Jackson 1997, "gabbro".

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 53.

- S2CID 129501077.

- ^ Jackson 1997, ferrodiorite.

- S2CID 219741493.

- ISBN 9780199653065.

- S2CID 240591656.

- ISBN 047157452X.

- doi:10.1130/B31586.1.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 378.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 99.

- ^ Boynton, Helen (2008). "Update on Charnian Fossils" (PDF). Mercian Geologist. 17 (1): 52. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- S2CID 129097226.

- ^ Zeh, A.; Will, T.M. (2010). "The mid-German crystalline zone". Pre-Mesozoic Geology of Saxo-Thuringia—From the Cadomian Active Margin to the Variscan Orogen. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart. pp. 195–220. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- .

- S2CID 130903053.

- S2CID 129191837.

- ^ Muller, J.E. (1980). Geology Victoria Map 1553A. Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada

- .

- ISBN 0-8137-2265-9.

- S2CID 225003517.

- ISBN 9781607810049.

- ^ Jackson 1997, corsite.

- ^ Jackson 1997, markfieldite.

- .

- ISBN 9781317415527.

- .

- ISBN 978-3-540-78593-4.

- ISBN 9780203930960.

- S2CID 162152616.

- . Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Siddall, R.; Schroder, J.K.; Hamilton, L. (2016). "Building Birmingham: A tour in three parts of the building stones used in the city centre.; Part 2: Centenary Square to Brindley Place" (PDF). Urban Geology in the English Midlands. 2. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ISBN 9781785702785.

- ^ "diorite | rock | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on Oct 10, 2022. Retrieved 2022-07-13.

![Statue of Amun; 1336-1327 BC; height: 220 cm (87 in), width: 44[clarification needed], length: 78 cm (31 in); Louvre](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4e/Paris_-_Tout%C3%A2nkhamon%2C_le_Tr%C3%A9sor_du_Pharaon_-_Amon_prot%C3%A9geant_Tout%C3%A2nkhamon_-_005.jpg/113px-Paris_-_Tout%C3%A2nkhamon%2C_le_Tr%C3%A9sor_du_Pharaon_-_Amon_prot%C3%A9geant_Tout%C3%A2nkhamon_-_005.jpg)