Hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome

| Hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | HBOC |

| |

| Ovarian and breast cancer patients in a pedigree chart of a family | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics and gynaecology, endocrinology, dermatology, oncology, medical genetics |

Hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndromes (HBOC) are

Most hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndromes are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Biallelic and homozygous inheritance of defective alleles that confer this syndrome is usually an embryonically lethal condition; live cases usually experience a severe form of Fanconi anemia.

Causes

A number of genes are associated with HBOC.[5] The most common of the known causes of HBOC are:

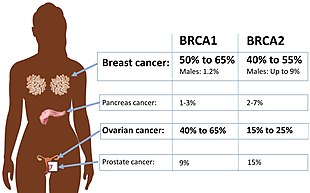

- BRCA mutations:[5] Harmful mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes can produce very high rates of breast and ovarian cancer, as well as increased rates of other cancers. Mutations in BRCA1 are associated with a 39-46% risk of ovarian cancer and mutations in BRCA2 are associated with a 10-27% risk of ovarian cancer.[6]

Other identified genes include:

- MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2: mutations in genes that lead to Lynch Syndrome put individuals at risk for ovarian cancer.[7]

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome. It produces particularly high rates of breast cancer among younger women with mutated genes, and despite being rare, 4% of women with breast cancer under age 30 have a mutation in this gene.[5]

- clinical signs, as well as an increased risk for many cancers.[5]

- gastric cancer.[5]

- STK11: Mutations produce Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. It is extremely rare, and creates a predisposition to breast cancer, intestinal cancer, and pancreatic cancer.[5]

- colon cancer and prostate cancer.[5]

- ataxia telangectasia; female carriers have approximately double the normal risk of developing breast cancer.[5]

- PALB2: Studies vary in their estimate of the risk from mutations in this gene and the frequency of mutations in this gene may be different among different populations.[8] It may be moderate risk, or as high as BRCA2.[5]

For many of these genes, inheriting both defective alleles usually result in an embryonically lethal phenotype. Live cases suffer from a severe form of

Approximately 45% of HBOC cases involve unidentified genes, or multiple genes.[5]

Diagnosis

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2023) |

Prevention

People with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are recommended to have a

Prophylactic

References

- ISBN 978-1-4987-4428-7.

- ^ "Hereditary Breast Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (BRCA1 / BRCA2)". Stanford University. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- PMID 31270479.

- PMID 20301425.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-59102-776-8.

- ^ S2CID 29024566.

- S2CID 46967266.

- ^ PMID 31206626.

- PMID 25472942.

- .

- S2CID 231876899.