Historiography of World War I

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (November 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The first tentative efforts to comprehend the meaning and consequences of

Historian Heather Jones argues that the

Causes of the war

The identification of the causes of World War I remains a debated issue. World War I began in the Balkans on July 28, 1914, and hostilities ended on November 11, 1918, leaving 17 million dead and 25 million wounded. Moreover, the Russian Civil War can in many ways be considered a continuation of World War I, as can various other conflicts in the direct aftermath of 1918.

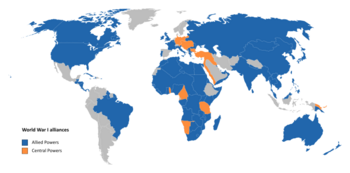

Scholars looking at the long term seek to explain why two rival sets of powers (the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire against the Russian Empire, France, and the British Empire) came into conflict by the start of 1914. They look at such factors as political, territorial and economic competition;

Scholars seeking short-term analysis focus on the summer of 1914 and ask whether the conflict could have been stopped, or instead whether deeper causes made it inevitable. Among the immediate causes were the decisions made by statesmen and generals during the

The crisis followed a series of diplomatic clashes among the

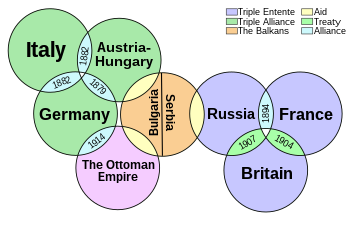

"Web of alliances" narratives

.Although general narratives of the war tend to emphasize the importance of

The most important alliances in Europe required participants to agree to collective defence if they were attacked. Some represented formal alliances, but the Triple Entente represented only a frame of mind:

- German-Austrian Treaty (1879)

- The Franco-Russian Alliance (1894)

- The addition of Italy to the Germany and Austrian alliance in 1882, forming the Triple Alliance

- Treaty of London, 1839, guaranteeing the neutrality of Belgium

There are three notable exceptions that demonstrate that alliances did not in themselves force the great powers to act:

- The entente" between Britain and Russia (1907) formed the so-called Triple Entente. However, the Triple Entente did not, in fact, force Britain to mobilise because it was not a military treaty.

- Moreover, general narratives of the war regularly misstate that Russia was allied to Serbia. Clive Ponting noted: "Russia had no treaty of alliance with Serbia and was under no obligation to support it diplomatically, let alone go to its defence."[14]

- Italy, despite being part of the Triple Alliance, did not enter the war to defend the Triple Alliance partners.

Cultural memory in the United Kingdom

World War I had a lasting impact on collective memory of the United Kingdom. It was seen by many in Britain as signalling the end of an era of stability stretching back to the Victorian period, and across Europe many regarded it as a watershed.[15] Historian Samuel Hynes explained:

A generation of innocent young men, their heads full of high abstractions like Honour, Glory and England, went off to war to make the world safe for democracy. They were slaughtered in stupid battles planned by stupid generals. Those who survived were shocked, disillusioned and embittered by their war experiences, and saw that their real enemies were not the Germans, but the old men at home who had lied to them. They rejected the values of the society that had sent them to war, and in doing so separated their own generation from the past and from their cultural inheritance.[16]

This has become the most common perception of World War I, perpetuated by the art, cinema, poems, and stories published subsequently. Films such as

Discontent in Germany and Austria

The rise of Nazism and fascism included a revival of the nationalist spirit and a rejection of many post-war changes. Similarly, the popularity of the stab-in-the-back legend (German: Dolchstoßlegende) was a testament to the psychological state of defeated Germany, and was a rejection of responsibility for the conflict. This conspiracy theory of the betrayal of the German war effort by Jews became common, and the German populace came to see themselves as victims. The widespread acceptance of the "stab-in-the-back" myth delegitimised the Weimar government and destabilised the system, opening it to extremes of right and left. The same occurred in Austria, which did not consider itself responsible for the outbreak of the war, and claimed not to have suffered a military defeat.[20]

Enabling the rise of totalitarianism

Social trauma

The social trauma caused by unprecedented rates of casualties manifested itself in different ways, which have been the subject of subsequent historical debate.[26] Over 8 million Europeans died in the war. Millions suffered permanent disabilities. The war gave birth to fascism and Bolshevism and destroyed the centuries-old dynasties that had ruled the Ottoman, Habsburg, Russian and German Empires.[1]

The optimism of la belle époque was destroyed, and those who had fought in the war were referred to as the Lost Generation.[27] For years afterward, people mourned the dead, the missing, and the many disabled.[28] Many soldiers returned with severe trauma, suffering from shell shock (also called neurasthenia, a condition related to post-traumatic stress disorder).[29] Many more returned home with few after-effects; however, their silence about the war contributed to the conflict's growing mythological status. Though many participants did not share in the experiences of combat or spend any significant time at the front, or had positive memories of their service, the images of suffering and trauma became the widely shared perception. Such historians as Dan Todman, Paul Fussell, and Samuel Heyns have all published works since the 1990s arguing that these common perceptions of the war are factually incorrect.[26]

See also

- Bibliography of World War I § Historiography and memory

- Historiography of World War II

- World War I in popular culture

References

- ^ a b Neiberg, Michael (2007). The World War I Reader. p. 1.

- ^ "The intro the outbreak of the First World War". Cambridge Blog. 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- .

- ^ see Christoph Cornelissen, and Arndt Weinrich, eds. Writing the Great War – The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present (2020) free download Archived 29 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine; full coverage for major countries.

- ^ JSTOR 2538636.

- ISBN 978-0-3930-5480-4.

- S2CID 154759602.

- ^ S2CID 154923423.

- S2CID 55976453.

- S2CID 153783717.

- ISBN 978-1-134-85200-0.

- ISBN 978-0-312-69611-5.

- ^ Explaining the Outbreak of the First World War – Closing Conference Genève Histoire et Cité 2015; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uWDJfraJWf0 See13:50

- ^ Ponting (2002), p. 122.

- ISBN 978-1-84511-883-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-689-12128-9.

- ^ a b c Todman 2005, pp. 153–221.

- ISBN 978-0-19-513332-5. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ^ "In Our Time Soldier's Home Summary & Analysis". SparkNotes. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- OCLC 913003568.

- ^ Kitchen, Martin. "The Ending of World War One, and the Legacy of Peace". BBC. Archived from the original on 18 July 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ^ Baker 2006.

- ^ Chickering 2004.

- ^ "World War II". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5.

- ^ a b Todman 2005, pp. xi–xv.

- ^ Roden.

- ^ Wohl 1979.

- ^ Tucker & Roberts 2005, pp. 108–1086.

Bibliography

- Baker, Kevin (June 2006). "Stabbed in the Back! The past and future of a right-wing myth". Harper's Magazine.

- Chickering, Rodger (2004). Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914–1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 55523473.

- ISBN 978-0-7011-7293-0.

- Roden, Mike. "The Lost Generation – myth and reality". Aftermath – when the Boys Came Home. Archived from the original on 1 December 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Todman, Dan (2005). The Great War: Myth and Memory. A & C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-6728-7.

- Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). Encyclopedia of World War I. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. OCLC 61247250.

- Wohl, Robert (1979). The Generation of 1914 (3rd ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-34466-2.