History of numerical weather prediction

The history of numerical weather prediction considers how current weather conditions as input into

Because the output of forecast models based on

Background

Until the end of the 19th century, weather prediction was entirely subjective and based on empirical rules, with only limited understanding of the physical mechanisms behind weather processes. In 1901

In 1922, Lewis Fry Richardson published the first attempt at forecasting the weather numerically. Using a hydrostatic variation of Bjerknes's primitive equations,[2] Richardson produced by hand a 6-hour forecast for the state of the atmosphere over two points in central Europe, taking at least six weeks to do so.[3] His forecast calculated that the change in surface pressure would be 145 millibars (4.3 inHg), an unrealistic value incorrect by two orders of magnitude. The large error was caused by an imbalance in the pressure and wind velocity fields used as the initial conditions in his analysis.[2]

The first successful numerical prediction was performed using the

In the United Kingdom the

Early years

In September 1954,

Later models used more complete equations for atmospheric dynamics and

Global forecast models

A global forecast model is a weather forecasting model which initializes and forecasts the weather throughout the Earth's

The National Meteorological Center's Global Spectral Model was introduced during August 1980.[14] The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts model debuted on May 1, 1985.[25] The United Kingdom Met Office has been running their global model since the late 1980s,[26] adding a 3D-Var data assimilation scheme in mid-1999.[27] The Canadian Meteorological Centre has been running a global model since 1991.[28] The United States ran the Nested Grid Model (NGM) from 1987 to 2000, with some features lasting as late as 2009. Between 2000 and 2002, the Environmental Modeling Center ran the Aviation (AVN) model for shorter range forecasts and the Medium Range Forecast (MRF) model at longer time ranges. During this time, the AVN model was extended to the end of the forecast period, eliminating the need of the MRF and thereby replacing it. In late 2002, the AVN model was renamed the Global Forecast System (GFS).[29] The German Weather Service has been running their global hydrostatic model, the GME, using a hexagonal icosahedral grid since 2002.[30] The GFS is slated to eventually be supplanted by the Flow-following, finite-volume Icosahedral Model (FIM), which like the GME is gridded on a truncated icosahedron, in the mid-2010s.

Global climate models

In 1956,

Limited-area models

The horizontal domain of a model is either global, covering the entire Earth, or regional, covering only part of the Earth. Regional models (also known as limited-area models, or LAMs) allow for the use of finer (or smaller) grid spacing than global models. The available computational resources are focused on a specific area instead of being spread over the globe. This allows regional models to resolve explicitly smaller-scale meteorological phenomena that cannot be represented on the coarser grid of a global model. Regional models use a global model for initial conditions of the edge of their domain in order to allow systems from outside the regional model domain to move into its area. Uncertainty and errors within regional models are introduced by the global model used for the boundary conditions of the edge of the regional model, as well as errors attributable to the regional model itself.[39]

In the United States, the first operational regional model, the limited-area fine-mesh (LFM) model, was introduced in 1971.

The German Weather Service developed the High Resolution Regional Model (HRM) in 1999, which is widely run within the operational and research meteorological communities and run with hydrostatic assumptions.[44] The Antarctic Mesoscale Prediction System (AMPS) was developed for the southernmost continent in 2000 by the United States Antarctic Program.[45] The German non-hydrostatic Lokal-Modell for Europe (LME) has been run since 2002, and an increase in areal domain became operational on September 28, 2005.[46] The Japan Meteorological Agency has run a high-resolution, non-hydrostatic mesoscale model since September 2004.[47]

Air quality models

The technical literature on air pollution dispersion is quite extensive and dates back to the 1930s and earlier. One of the early air pollutant plume dispersion equations was derived by Bosanquet and Pearson.

To determine ΔH, many if not most of the air dispersion models developed between the late 1960s and the early 2000s used what are known as "the Briggs equations." G. A. Briggs first published his plume rise observations and comparisons in 1965.[50] In 1968, at a symposium sponsored by Conservation of Clean Air and Water in Europe, he compared many of the plume rise models then available in the literature.[51] In that same year, Briggs also wrote the section of the publication edited by Slade[52] dealing with the comparative analyses of plume rise models. That was followed in 1969 by his classical critical review of the entire plume rise literature,[53] in which he proposed a set of plume rise equations which have become widely known as "the Briggs equations". Subsequently, Briggs modified his 1969 plume rise equations in 1971 and in 1972.[54][55]

The Urban Airshed Model, a regional forecast model for the effects of

Tropical cyclone models

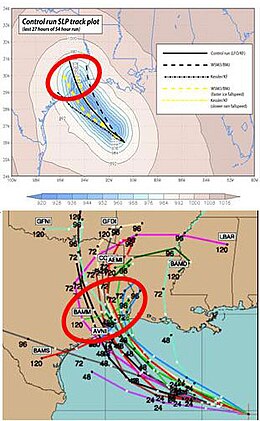

During 1972, the first model to forecast

The

Ocean models

The first ocean wave models were developed in the 1960s and 1970s. These models had the tendency to overestimate the role of wind in wave development and underplayed wave interactions. A lack of knowledge concerning how waves interacted among each other, assumptions regarding a maximum wave height, and deficiencies in computer power limited the performance of the models. After experiments were performed in 1968, 1969, and 1973, wind input from the Earth's atmosphere was weighted more accurately in the predictions. A second generation of models was developed in the 1980s, but they could not realistically model swell nor depict wind-driven waves (also known as wind waves) caused by rapidly changing wind fields, such as those within tropical cyclones. This caused the development of a third generation of wave models from 1988 onward.[67][68]

Within this third generation of models, the spectral wave transport equation is used to describe the change in wave spectrum over changing topography. It simulates wave generation, wave movement (propagation within a fluid), wave shoaling, refraction, energy transfer between waves, and wave dissipation.[69] Since surface winds are the primary forcing mechanism in the spectral wave transport equation, ocean wave models use information produced by numerical weather prediction models as inputs to determine how much energy is transferred from the atmosphere into the layer at the surface of the ocean. Along with dissipation of energy through whitecaps and resonance between waves, surface winds from numerical weather models allow for more accurate predictions of the state of the sea surface.[70]

Model output statistics

Because forecast models based upon the equations for atmospheric dynamics do not perfectly determine weather conditions near the ground, statistical corrections were developed to attempt to resolve this problem. Statistical models were created based upon the three-dimensional fields produced by numerical weather models, surface observations, and the climatological conditions for specific locations. These statistical models are collectively referred to as model output statistics (MOS),[71] and were developed by the National Weather Service for their suite of weather forecasting models by 1976.[72] The United States Air Force developed its own set of MOS based upon their dynamical weather model by 1983.[73]

Ensembles

As proposed by

Edward Epstein recognized in 1969 that the atmosphere could not be completely described with a single forecast run due to inherent uncertainty, and proposed a stochastic dynamic model that produced means and variances for the state of the atmosphere.[77] While these Monte Carlo simulations showed skill, in 1974 Cecil Leith revealed that they produced adequate forecasts only when the ensemble probability distribution was a representative sample of the probability distribution in the atmosphere.[78] It was not until 1992 that ensemble forecasts began being prepared by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, the Canadian Meteorological Centre,[79] and the National Centers for Environmental Prediction. The ECMWF model, the Ensemble Prediction System,[80] uses singular vectors to simulate the initial probability density, while the NCEP ensemble, the Global Ensemble Forecasting System, uses a technique known as vector breeding.[81][82]

See also

References

- . Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- ^ doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2007.02.034. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2010-07-08. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-85729-1.

- ^ Edwards, Paul. "Before 1955: Numerical Models and the Prehistory of AGCMs". Atmospheric General Circulation Modeling: A Participatory History. University of Michigan. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- ^ "THE ENIAC FORECASTS" (PDF).

- ^ Witman, Sarah (16 June 2017). "Meet the Computer Scientist You Should Thank For Your Smartphone's Weather App". Smithsonian. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ISBN 978-0262013925. Archived from the originalon 2012-01-27. Retrieved 2017-07-22.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-0-471-38108-2.

- ^ "History of numerical weather prediction". Met Office. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright.

- .

- ^ American Institute of Physics (2008-03-25). "Atmospheric General Circulation Modeling". Archived from the original on 2008-03-25. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ^ ISSN 1520-0434.

- ^ )

- ^ Gates, W. Lawrence; Pocinki, Leon S.; Jenkins, Carl F. (August 1955). Results Of Numerical Forecasting With The Barotropic And Thermotropic Atmospheric Models (PDF). Hanscom Air Force Base: Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratories. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2020. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- ISSN 1520-0469.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-2940-0.

- ^ a b Leslie, L.M.; Dietachmeyer, G.S. (December 1992). "Real-time limited area numerical weather prediction in Australia: a historical perspective" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. 41 (SP): 61–77. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ISBN 978-0-521-86540-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-31256-1.

- ISBN 978-0-12-554766-6.

- ISBN 978-0-12-554766-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89871-567-5.

- ISBN 978-0-12-554766-6.

- ^ European Center for Medium Range Forecasts (2002-01-21). "Brief history of the ECMWF analysis and forecasting system". Archived from the original on 2011-02-01. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ British Atmospheric Data Centre (2007-01-05). "The History of the Unified Model". Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ Candy, Brett, Stephen English, Richard Renshaw, and Bruce Macpherson (2004-02-27). "Use of AMSU data in the Met Office UK Mesoscale Model" (PDF). Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies. p. 1. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - .

- ^ Environmental Modeling Center (2010). "Model Changes Since 1991". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- doi:10.5194/gmdd-4-419-2011.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - .

- ISBN 978-0-471-38108-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-85729-1.

- ^ "Breakthrough article on the First Climate Model".

- ^ Collins, William D.; et al. (June 2004). "Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 3.0)" (PDF). University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- doi:10.1029/95JD02169. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2010-07-10. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- ISBN 978-0-470-85751-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4303-1696-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-51389-0.

- ^ Explanation of Current NGM MOS. National Weather Service Meteorological Development Lab (1999). Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ ISSN 1520-0493.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Puri, K., G. S. Dietachmayer, G. A. Mills, N. E. Davidson, R. A. Bowen, L. W. Logan (September 1998). "The new BMRC Limited Area Prediction System, LAPS". Australian Meteorological Magazine. 47 (3): 203–223.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ISSN 1520-0493.

- ^ Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center (2009-09-29). "HRM – Atmospheric Model". Archived from the original on 2012-04-03. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ISBN 978-1-84816-485-7.

- ^ Schultz, J.-P. (2006). "The New Lokal-Modell LME of the German Weather Service" (PDF). Consortium for Small-scale Modeling (6). Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ^ Narita, Masami; Shiro Ohmori (2007-08-06). "3.7 Improving Precipitation Forecasts by the Operational Nonhydrostatic Mesoscale Model with the Kain-Fritsch Convective Parameterization and Cloud Microphysics" (PDF). 12th Conference on Mesoscale Processes. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ^ Bosanquet, C. H. and Pearson, J. L., "The spread of smoke and gases from chimneys", Transactions of the Faraday Society, 32:1249, 1936

- ^ Sutton, O. G., "The problem of diffusion in the lower atmosphere", Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 73:257, 1947 and "The theoretical distribution of airborne pollution from factory chimneys", Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 73:426, 1947

- ^ Briggs, G. A., "A plume rise model compared with observations", Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association, 15:433–438, 1965

- ^ Briggs, G.A., "CONCAWE meeting: discussion of the comparative consequences of different plume rise formulas", Atmospheric Environment, 2:228–232, 1968

- ^ Slade, D. H. (editor), "Meteorology and atomic energy 1968", Air Resources Laboratory, U.S. Dept. of Commerce, 1968

- ^ Briggs, G. A., "Plume Rise", United States Army Environmental Command Critical Review Series, 1969

- ^ Briggs, G. A., "Some recent analyses of plume rise observation", Proceedings of the Second International Clean Air Congress, Academic Press, New York, 1971

- ^ Briggs, G. A., "Discussion: chimney plumes in neutral and stable surroundings", Atmospheric Environment, 6:507–510, 1972

- ISBN 978-0-306-43828-8.

- ^ Community Modeling; Analysis System Center (June 2010). "Welcome to CMAQ-Model.org". University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on December 11, 2009. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ Marz, Loren C. (2009-11-04). "North American Mesoscale (NAM) – Community Multi-scale Air Quality (CMAQ) Ozone Forecast Verification for Knoxville, Tennessee (Summer 2005)". Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ Anselmo, David, Michael D. Moran, Sylvain Ménard, Véronique S. Bouchet, Paul A. Makar, Wanmin Gong, Alexander Kallaur, Paul-André Beaulieu, Hugo Landry, Craig Stroud, Ping Huang, Sunling Gong, and Donald Talbot (2010). "J10.4: A New Canadian Air Quality Forecast Model: GEM-MACH15" (PDF). 16th Conference on Air Pollution Meteorology. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jelesnianski, C. P., J. Chen, and W. A. Shaffer (April 1992). "SLOSH: Sea, lake, and Overland Surges from Hurricanes. NOAA Technical Report NWS 48" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 2. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Franklin, James (2010-04-20). "National Hurricane Center Forecast Verification". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ^ Le Marshall; J. F.; L. M. Leslie; A. F. Bennett (1996). "Tropical Cyclone Beti - an Example of the Benefits of Assimilating Hourly Satellite Wind Data" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. 45: 275.

- ^ Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (2011-01-28). "Operational Hurricane Track and Intensity Forecasting". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ "Weather Forecast Accuracy Gets Boost with New Computer Model". UCAR press release. Archived from the original on 2007-05-19. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ "New Advanced Hurricane Model Aids NOAA Forecasters". NOAA Magazine. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- S2CID 14845745.

- ISBN 978-0-521-57781-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-3-540-24430-1.

- ISBN 978-0-415-41578-1.

- ISSN 1520-0426.

- ISBN 978-0-275-22129-4.

- ^ Harry Hughes (1976). Model output statistics forecast guidance. United States Air Force Environmental Technical Applications Center. pp. 1–16.

- ^ L. Best; D. L.; S. P. Pryor (1983). Air Weather Service Model Output Statistics Systems. Air Force Global Weather Central. pp. 1–90.

- ISBN 978-0-471-38108-2.

- Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- Climate Diagnostics Center. Retrieved 2007-02-16.

- .

- ISSN 1520-0493.

- ^ Houtekamer, Petere; Gérard Pellerin (2004-11-12). "The Canadian ensemble prediction system (EPS)" (PDF). Environmental Modeling Center. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ECMWF. Archived from the originalon 2010-10-30. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- S2CID 14668576.

- .