Kenji Doihara

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2020) |

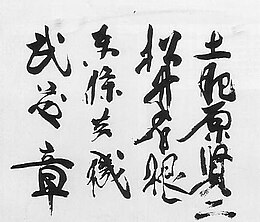

Doihara Kenji | |

|---|---|

Occupied Japan

| |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Allegiance | |

| Awards | Order of the Rising Sun |

Kenji Doihara (土肥原 賢二, Doihara Kenji, 8 August 1883 – 23 December 1948) was a Japanese

As a leading intelligence officer, he played a key role to the Japanese machinations that led to the occupation of large parts of China, the destabilization of the country, and the disintegration of the traditional structure of

After the end of World War II, he was prosecuted for

Early life and career

Kenji Doihara was born in

Doihara longed for a high-ranking military career, but his family's low social status stood in the way. He therefore contrived to use his 15-year-old sister as a

He learned to speak fluent

Member of the "Eleven Reliable" clique

Doihara's performance was recognized, and by 1930 he was assigned to the

"Lawrence of Manchuria”

While at Tianjin, Doihara, together with Seishirō Itagaki engineered the infamous

Next, Doihara took the task to return former

In early 1932, Doihara was sent to head the Harbin Special Agency of the Kwantung Army, where he began negotiations with General

Ma's fame as an uncompromising fighter against the Japanese invaders survived after his defeat and so Doihara made contact with him offering a huge sum of money and the command of the puppet state's

From 1932 to 1933, the newly promoted

For the key role he played in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, he earned the nickname "Lawrence of Manchuria," a reference to

Second Sino-Japanese War and Second World War

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

From 1936 to 1937, Doihara was the commander of the 1st Depot Division in Japan until the

After the Battle of Lanfeng, Doihara was attached to the Army General Staff as head of the Doihara Special Agency until 1939, when he was given command of the

In 1940, Doihara became a member of the

In 1943, Doihara was made

Returning to Japan in 1945, Doihara was promoted to

Criminal activities

Doihara's activity in China vastly exceeded the normal behaviour of an intelligence officer. As chief of the Japanese secret services in China, he worked out, put in motion, and oversaw a wide series of activities, systematically exploiting the occupied areas and disrupting Chinese social structure in the rest of the country to weaken public resistance by using every possible kind of action, including deliberately fueling criminality; fostering drug addiction; sponsoring terrorism, assassinations, blackmail, bribery, opium trafficking, and racketeering; and spreading every kind of corruption in the almost-ungovernable country.[8] The extent of his activities and covert operations is still inadequately understood. According to Ronald Sydney Seth, his activity played a key role in shattering China's ability to confront Japan's expansion by generating chaotic conditions, which prevented any mass reaction in the invaded country.

After the occupation of Manchuria, the Japanese secret service, under his supervision, soon turned Manchukuo into a vast criminal enterprise in which rape, child molestation, sexual humiliation, sadism, assault, and murder became institutionalized means of terrorizing and controlling Manchuria's Chinese and Russian populations. Robbery by soldiers and gendarmes of the

Doihara soon expanded his activity into the still unoccupied parts of China. By using about 80,000 paid Chinese villains known as Chiang Mao Tao, he funded hundreds of criminal groups, using them for every kind of social disturbance, turnover, assassinations and sabotage inside unoccupied China. Through the organizations, he soon managed to control a large part of the opium traffic in China, using the money earned to fund his covert operations.[10][11]

He hired an army of agents and sent them throughout China as representatives of various humanitarian organizations. They established thousands of health centers, mainly in the villages of the districts, for curing tuberculosis, which was then epidemic in China. By adulterating medicines with opium, he managed to addict millions of unsuspecting patients, expanding societal degeneration into areas which had been hitherto untouched by the increasing breakdown of Chinese society. The scheme also created a pool of addicted victims desperate to offer any kind of service to secure a daily dose of opium.[12][13]

He initially gave food and shelter to tens of thousands Russian

Winning the necessary support from the authorities in Tokyo he persuaded the Japanese tobacco industry Mitsui of Mitsui Zaibatsu to produce special cigarettes bearing the popular to the Far East trademark "Golden Bat". Their circulation was prohibited in Japan, as they were intended only for export. Doihara's services controlled their distribution in China and Manchuria where the full production was exported. In the mouthpiece of each cigarette a small dose of opium or heroin was concealed, and by this subterfuge millions of unsuspecting consumers were added to the ever-growing crowds of drug addicts in the crippled country, simultaneously creating huge profits. According to testimony presented at the Tokyo War Crimes trials in 1948, the revenue from the narcotization policy in China, including Manchukuo, was estimated as twenty to thirty million yen per year, while another authority[who?] stated during the trial that the annual revenue was estimated by the Japanese military at 300 million dollars a year.[16]

Given the chaotic situation in China, the corruption Doihara methodically spread did not take long to reach the very top. In 1938, Chiang had eight generals, all in command of Chinese divisions, executed when it was found that they were informers for Doihara's services. This heralded a wave of executions of high-ranking Chinese officials found guilty for every kind of dealing with Doihara during the next six years of the war. To many Westerners in touch with the Chinese leadership, the purges did not have lasting results.[citation needed]

Prosecution and conviction

After the

See also

References

- ISBN 9780816060016, 2006

- ISBN 9780385016094, Doubleday, 1974

- ISBN 9781846032172, 2008

- ^ Sims, Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation 1868–2000

- ISBN 9780714656908, 2005

- ISBN 0-714-65690-9.

- ISBN 9780674018280.

- ^ The peace conspiracy: Wang Ching-wei and the China war, 1937-1941, vol. 67, Harvard East Asian Series, The East Asian Research Center at Harvard University, Harvard University Press, 1972

- ISBN 9780714656908, 2005

- ISBN 978-0-385-01609-4, Doubleday, 1974

- ISBN 9780816060016, 2006

- ^ Secret servants: a history of Japanese espionage, p.128, Ronald Sydney Seth, ASIN: B0007DM4XG, Straus and Cudahy, 1957

- ISBN 9781580860154

- ISBN 9780385016094, Doubleday, 1974

- ISBN 978-0714656908, 2005

- ISBN 9780834800809

- ISBN 0275957594

- ^ Maga, Judgment at Tokyo

Books

- Beasley, W.G. (1991). Japanese Imperialism 1894–1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822168-1.

- Barrett, David (2001). Chinese Collaboration with Japan, 1932–1945: The Limits of Accommodation. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3768-1.

- ISBN 0-06-093130-2.

- Fuller, Richard (1992). Shokan: Hirohito's Samurai. London: Arms and Armor. ISBN 1-85409-151-4.

- Hayashi, Saburo; Cox, Alvin D (1959). Kogun: The Japanese Army in the Pacific War. Quantico, VA: The Marine Corps Association.

- Maga, Timothy P. (2001). Judgment at Tokyo: The Japanese War Crimes Trials. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2177-9.

- Minear, Richard H. (1971). Victor's Justice: The Tokyo War Crimes Trial. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.

- ISBN 0-8129-6858-1.

- Wasserstein, Bernard (1999). Secret War in Shanghai: An Untold Story of Espionage, Intrigue, and Treason in World War II. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-98537-4.

External links

- Ammenthorp, Steen. "Kenji Doihara". The Generals of World War II.

- "Scholar, Simpleton & Inflation". Time Magazine. 1932-04-25. Archived from the originalon September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- Newspaper clippings about Kenji Doihara in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW