Kraak ware

Kraak ware or Kraak porcelain (Dutch Kraakporselein) is a type of Chinese export porcelain produced mainly in the late Ming dynasty, in the Wanli reign (1573–1620), but also in the Tianqi (1620–1627) and the Chongzhen (1627–1644).[1] It was among the first Chinese export wares to arrive in Europe in mass quantities, and was frequently featured in Dutch Golden Age paintings of still life subjects with foreign luxuries.

The wares have "suffered from imprecise terminology", sometimes being loosely used for many varieties of Chinese export

The quality of the porcelain used to form Kraak ware is much disputed among scholars; some claim that it is surprisingly good, in certain cases indistinguishable from that produced on the domestic market;[4] others imply that it is a dismal shadow of the truly fine ceramics China was capable of producing.[5] Rinaldi comes to a more even-handed conclusion, noting that it "forms a middle category between much heavier wares, often coarse, and definitely finer wares with well levigated clay and smooth glaze that does not shrink on the rim... " Thus looking at ceramic production in China at the time from a larger prospective, Kraak ware falls between the best examples and a typical provincial output, such as the contemporary Swatow ware, also made for export, but to South-East Asia and Japan.[6]

Name

Kraak porcelain is believed to be named after the

Style

Kraak ware is almost all painted in the

Shapes included

The specialist Maura Rinaldi suggests that the latter type was designed specifically to serve a European clientele, since there do not seem to be many surviving examples elsewhere in the world, even in the spectacular Topkapı Palace collection, which houses the most extensive selection of Kraak ware of all. Noting the importance of soups and stews in European diet, Rinaldi proposes that klapmusten were developed to satisfy a foreign demand, noting that the heavy, long-handled, metal spoon that is common in Europe would have toppled and chipped the high-walled Chinese bowl.[10]

-

Jingdezhen, Wanli period

-

Dish with figure

-

Bowl, c. 1600

-

Bowl, c. 1600

-

Last piece from below

-

Kraak porcelain plate 20 cm across

-

Kraak dish. Porcelain decorated with underglaze blue. 1591-1613 CE. From Jingdezhen, China. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Influence

Kraak was copied and imitated all over the world, by potters in

Today a great deal is learned about Kraak ware through

Gallery of Kraak ware imitations made outside China

-

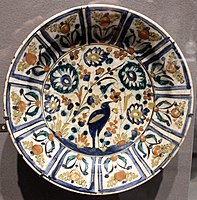

Iran, probably Isfahan, 1580-1630

-

Iran, probably Isfahan, 1580-1630

-

French Nevers faience, Conrade factory, 1630s

-

Japanese export porcelain, for the European market, c. 1670

-

"Possibly German", late 17th-century

-

Japan, Arita ware, c. 1690-1700

-

England,Chelsea porcelain, c. 1752-1755

-

Iran, 18th-century

Notes

- ^ Vinhais L and Welsh J: Kraak Porcelain: the Rise of Global Trade in the 16th and early 17th centuries. Jorge Welsh Books 2008, p. 17

- ^ Vainker, 147

- ^ Vainker, 147

- ^ Howard, p. 1 of "Introduction;" Crowe, p. 11

- ^ Kerr, p. 38.

- ^ Rinaldi, pp. 12, 67.

- ^ Rinaldi, p. 32

- ^ Rinaldi, p. 60; Kerr, p. 38.

- ^ "- Errors".

- ^ Rinaldi, pp. 11, 118.

- ^ Crowe, p. 22; Howard, p. 7 of "Introduction."

- ^ For a study on foreign objects in Dutch paintings, see Hochstrasser, Still Life and Trade.

- ^ Carswell, p. 168.

- ^ Crowe, p. 20; and Howard, p. 6 of "Introduction."

- ^ For a fascinating recent account, brilliantly illustrated, see Jörg, Porcelain from the Vung Tau wreck. A very brief online summary is here: [1]

References

- Carswell, John. Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and Its Impact on the Western World. Exhibition Catalogue. Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Gallery, 1985.

- Crowe, Yolande. Victoria & Albert Museum, 2002.

- Hochstrasser, Julie. Still Life and Trade in the Dutch Golden Age. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Howard, David and John Ayers. China for the West: Chinese Porcelain and other Decorative Arts for Export, Illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection. London and New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978.

- Jörg, Christiaan J.A. Porcelain from the Vung Tau wreck: The Hallstrom Excavation. Singapore: Sun Tree Publishing, 2001.

- Kerr, Rosemary. “Early Export Ceramics.” In Chinese Export Art and Design. Ed. Craig Clunas. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1987.

- Kroes, Jochem. Chinese Armorial Porcelain for the Dutch Market: Chinese Porcelain with Coats of Arms of Dutch Families. Den Haag: Centraal Bureau voor Generalogie and Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 2007.

- Rinaldi, Maura. Kraak Porcelain: A Moment in the History of Trade. London: Bamboo Pub, 1989.

- Vainker, S.J., Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, 1991, British Museum Press, 9780714114705

- Wu, Ruoming. The Origins of Kraak Porcelain in the ISBN 3-86705-074-0

External links

- Kraak Ware Dish, early 17th century; Chinese for the European market; Hard paste; Diam. 111⁄4 in. (28.6 cm); Metropolitan Museum, New York City, 1995.268.1 [2]

- Pair of Chinese Blue and White Kraak Ware Dishes, Wanli Reign; Christie's, London: Lot 478/Sale 5093, 29 March 2007

- Kraak ware collection in the Princesshof Museum, Leeuwarden Netherlands [3]

- A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics from The Metropolitan Museum of Art