Perineal hernia

| Perineum in humans | |

|---|---|

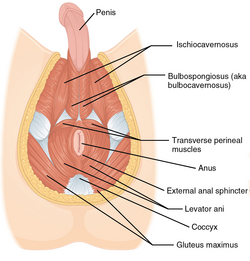

The muscles of the male perineum | |

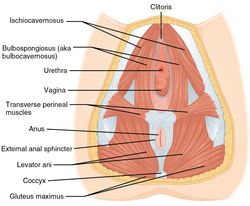

The muscles of the female perineum | |

| Anatomical terminology |

Perineal hernia is a

A common cause of perineal hernia is surgery involving the perineum.[

In humans

In humans, a major cause of perineal hernia is perineal surgery without adequate reconstruction. In some cases, particularly surgeries to remove the coccyx and distal sacrum, adequate reconstruction is very difficult to achieve. The posterior perineum is a preferred point of access for surgery in the

The standard surgical technique for repair of perineal hernia uses a prosthetic mesh,

In dogs and cats

In dogs, perineal hernia usually is found on the right side.

Dogs with benign prostatic hyperplasia have been found to have increased relaxin levels and suspected subsequent weakening of the pelvic diaphragm.[10] In cats, perineal hernias are seen most commonly following perineal urethrostomy surgery or secondary to megacolon.[11] Medical treatment consists of treatment of the underlying disease, enemas, and stool softeners. Because only about 20 percent of cases treated medically are free of symptoms, surgery is often necessary.[11] Recurrence is common with or without surgery.

Several surgeries have been described for perineal hernias in dogs. The current standard involves transposition of the internal obturator muscle. This technique has a lower recurrence and complication rate than traditional hernia repair. A new technique uses porcine small intestinal submucosa as a biomaterial to help repair the defect. This is can also be done in combination with internal obturator muscle transposition, especially when that muscle is weak.[12]

References

- ^ PMID 9207665.

- PMID 9840311.

- PMID 10743431.

- S2CID 10049165.

- ^ S2CID 33604955.

- PMID 18439796.

- PMID 12184704.

- ^ Seim, Howard B., III (2004). "Perineal Hernia Repair". Proceedings of the 29th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Perineal Hernia". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- S2CID 5754439.

- ^ a b Hoskins, Johnny D. (September 2006). "Anorectal Disease". DVM. Advanstar Communications: 8S–10S.

- ISBN 1-4160-0110-7.