Benign prostatic hyperplasia

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Benign enlargement of the prostate (BEP, BPE), adenofibromyomatous hyperplasia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, 5α-reductase inhibitors such as finasteride[1] |

| Frequency | 94 million men affected globally (2019)[3] |

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), also called prostate enlargement, is a noncancerous increase in size of the

The cause is unclear.[1] Risk factors include a family history, obesity, type 2 diabetes, not enough exercise, and erectile dysfunction.[1] Medications like pseudoephedrine, anticholinergics, and calcium channel blockers may worsen symptoms.[2] The underlying mechanism involves the prostate pressing on the urethra thereby making it difficult to pass urine out of the bladder.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and examination after ruling out other possible causes.[2]

Treatment options include lifestyle changes, medications, a number of procedures, and surgery.

As of 2019[update], about 94 million men aged 40 years and older are affected globally.

Signs and symptoms

BPH is the most common cause of

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) can be caused by BPH.[19] Symptoms are abdominal pain, a continuous feeling of a full bladder, frequent urination, acute urinary retention (inability to urinate), pain during urination (dysuria), problems starting urination (urinary hesitancy), slow urine flow, starting and stopping (urinary intermittency), and nocturia.[20]

BPH can be a progressive disease, especially if left untreated. Incomplete voiding results in residual urine or urinary stasis, which can lead to an increased risk of urinary tract infection.[21]

Causes

Hormones

Most experts consider androgens (testosterone and related hormones) to play a permissive role in the development of BPH. This means that androgens must be present for BPH to occur, but do not necessarily directly cause the condition. This is supported by evidence suggesting that castrated boys do not develop BPH when they age. In a study of 26 eunuchs from the palace of the Qing dynasty still living in Beijing in 1960, the prostate could not be felt in 81% of the studied eunuchs.[22] The average time since castration was 54 years (range, 41–65 years). On the other hand, some studies suggest that administering exogenous testosterone is not associated with a significant increase in the risk of BPH symptoms, so the role of testosterone in prostate cancer and BPH is still unclear. Further randomized controlled trials with more participants are needed to quantify any risk of giving exogenous testosterone.[23]

Testosterone promotes prostate cell proliferation,[26] but relatively low levels of serum testosterone are found in patients with BPH.[27][28] One small study has shown that medical castration lowers the serum and prostate hormone levels unevenly, having less effect on testosterone and dihydrotestosterone levels in the prostate.[29]

Besides testosterone and DHT, other androgens are also known to play a crucial role in BPH development. C

21 11-oxygenated steroids (pregnanes) have been identified are precursors to 11-oxygenated androgens which are also potent agonists for the androgen receptor.

While there is some evidence that estrogen may play a role in the cause of BPH, this effect appears to be mediated mainly through local conversion of androgens to estrogen in the prostate tissue rather than a direct effect of estrogen itself.[34] In canine in vivo studies castration, which significantly reduced androgen levels but left estrogen levels unchanged, caused significant atrophy of the prostate.[35] Studies looking for a correlation between prostatic hyperplasia and serum estrogen levels in humans have generally shown none.[28][36]

In 2008, Gat et al. published evidence that BPH is caused by failure in the spermatic venous drainage system resulting in increased hydrostatic pressure and local testosterone levels elevated more than 100-fold above serum levels.[37] If confirmed, this mechanism explains why serum androgen levels do not seem to correlate with BPH and why giving exogenous testosterone would not make much difference.

Diet

Studies indicate that dietary patterns may affect the development of BPH, but further research is needed to clarify any important relationship.[38] Studies from China suggest that greater protein intake may be a factor in the development of BPH. Men older than 60 in rural areas had very low rates of clinical BPH, while men living in cities and consuming more animal protein had a higher incidence.[39][40] On the other hand, a study in Japanese-American men in Hawaii found a strong negative association with alcohol intake, but a weak positive association with beef intake.[41] In a large prospective cohort study in the US (the Health Professionals Follow-up Study), investigators reported modest associations between BPH (men with strong symptoms of BPH or surgically confirmed BPH) and total energy and protein, but not fat intake.[42] There is also epidemiological evidence linking BPH with metabolic syndrome (concurrent obesity, impaired glucose metabolism and diabetes, high triglyceride levels, high levels of low-density cholesterol, and hypertension).[43]

Degeneration

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is an age-related disease. Misrepair-accumulation aging theory[44] suggests that the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia is a consequence of fibrosis and weakening of the muscular tissue in the prostate.[45] The muscular tissue is important in the functionality of the prostate, and provides the force for excreting the fluid produced by prostatic glands. However, repeated contractions and dilations of myofibers will unavoidably cause injuries and broken myofibers. Myofibers have a low potential for regeneration; therefore, collagen fibers need to be used to replace the broken myofibers. Such misrepairs make the muscular tissue weak in functioning, and the fluid secreted by glands cannot be excreted completely. Then, the accumulation of fluid in glands increases the resistance of muscular tissue during the movements of contractions and dilations, and more and more myofibers will be broken and replaced by collagen fibers.[46]

Pathophysiology

As men age, the enzymes

Both the glandular epithelial cells and the stromal cells (including muscular fibers) undergo hyperplasia in BPH.[2] Most sources agree that of the two tissues, stromal hyperplasia predominates, but the exact ratio of the two is unclear.[47]: 694

Anatomically the median and lateral lobes are usually enlarged, due to their highly glandular composition. The anterior lobe has little in the way of glandular tissue and is seldom enlarged. (Carcinoma of the prostate typically occurs in the posterior lobe – hence the ability to discern an irregular outline per rectal examination). The earliest microscopic signs of BPH usually begin between the age of 30 and 50 years old in the PUG, which is posterior to the proximal urethra.[47]: 694 In BPH, the majority of growth occurs in the transition zone (TZ) of the prostate.[47]: 694 In addition to these two classic areas, the peripheral zone (PZ) is also involved to a lesser extent.[47]: 695 Prostatic cancer typically occurs in the PZ. However, BPH nodules, usually from the TZ are often biopsied anyway to rule out cancer in the TZ.[47]: 695 BPH can be a progressive growth that in rare instances leads to exceptional enlargement.[48] In some males, the prostate enlargement exceeds 200 to 500 grams.[48] This condition has been defined as giant prostatic hyperplasia (GPH).[48]

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of BPH is based on a history of LUTS (lower urinary tract symptoms), a digital rectal exam, and the exclusion of other causes of similar signs and symptoms. The degree of LUTS does not necessarily correspond to the size of the prostate. An enlarged prostate gland on rectal examination that is symmetric and smooth supports a diagnosis of BPH.[2] However, if the prostate gland feels asymmetrical, firm, or nodular, this raises concern for prostate cancer.[2]

Validated questionnaires such as the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI), the International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS), and more recently the UWIN score (urgency, weak stream, incomplete emptying, and nocturia) are useful aids to making the diagnosis of BPH and quantifying the severity of symptoms.[2][49][50]

Laboratory investigations

Imaging and other investigations

Uroflowmetry is done to measure the rate of urine flow and total volume of urine voided when the subject is urinating.[51]

Abdominal ultrasound examination of the prostate and kidneys is often performed to rule out hydronephrosis and hydroureter. Incidentally, cysts, tumours, and stones may be found on ultrasound. Post-void residual volume of more than 100 ml may indicate significant obstruction.[52] Prostate size of 30 cc or more indicates enlargement of the prostate.[53]

Prostatic calcification can be detected through transrectal ultrasound (TRUS). Calcification is due to solidification of prostatic secretions or calcified corpora amylacea (hyaline masses on the prostate gland). Calcification is also found in a variety of other conditions such as prostatitis, chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and prostate cancer.[54][55] For those with elevated levels of PSA, TRUS guided biopsy is performed to take a sample of the prostate for investigation.[56] Although MRI is more accurate than TRUS in determining prostate volume, TRUS is less expensive and almost as accurate as MRI. Therefore, TRUS is still preferred to measure prostate volume.[57]

Differential diagnosis

Medical conditions

The differential diagnosis for LUTS is broad and includes various medical conditions, neurologic disorders, and other diseases of the bladder, urethra, and prostate such as

Medications

Certain medications can increase urination difficulties by increasing bladder outlet resistance due to increased

-

Micrograph showing nodular hyperplasia (left off center) of the prostate from a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). H&E stain.

-

Microscopic examination of different types of prostate tissues (stained withProstatic adenocarcinoma(PCA).

Management

When treating and managing benign prostatic hyperplasia, the aim is to prevent complications related to the disease and improve or relieve symptoms.[58] Approaches used include lifestyle modifications, medications, catheterization, and surgery.

Lifestyle

Lifestyle alterations to address the symptoms of BPH include physical activity,[59] decreasing fluid intake before bedtime, moderating the consumption of alcohol and caffeine-containing products, and following a timed voiding schedule.

Patients can also attempt to avoid products and medications with anticholinergic properties that may exacerbate urinary retention symptoms of BPH, including antihistamines, decongestants, opioids, and tricyclic antidepressants; however, changes in medications should be done with input from a medical professional.[60]

Physical activity

Physical activity has been recommended as a treatment for urinary tract symptoms. A 2019 Cochrane review of six studies involving 652 men assessing the effects of physical activity alone, and physical activity as a part of a self-management program, among others. However, the quality of evidence was very low and therefore it remains uncertain whether physical activity is helpful in men experiencing urinary symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia.[61]

Voiding position

Voiding position when urinating may influence urodynamic parameters (urinary flow rate, voiding time, and post-void residual volume).[62] A meta-analysis found no differences between the standing and sitting positions for healthy males, but that, for elderly males with lower urinary tract symptoms, voiding in the sitting position-- [63]

- decreased the post-void residual volume;

- increased the maximum urinary flow, comparable with pharmacological intervention; and

- decreased the voiding time.

This

Medications

The two main medication classes for BPH management are

Alpha-blockers

Selective α1-blockers are the most common choice for initial therapy.[65][66][67] They include alfuzosin,[68][69] doxazosin,[70] silodosin, tamsulosin, terazosin, and naftopidil.[58] They have a small to moderate benefit at improving symptoms.[71][58][72] Selective alpha-1 blockers are similar in effectiveness but have slightly different side effect profiles.[71][58][72] Alpha blockers relax smooth muscle in the prostate and the bladder neck, thus decreasing the blockage of urine flow. Common side effects of alpha-blockers include orthostatic hypotension (a head rush or dizzy spell when standing up or stretching), ejaculation changes, erectile dysfunction,[73] headaches, nasal congestion, and weakness. For men with LUTS due to an enlarged prostate, the effects of naftopidil, tamsulosin, and silodosin on urinary symptoms and quality of life may be similar.[58] Naftopidil and tamsulosin may have similar levels of unwanted sexual side effects but fewer unwanted side effects than silodosin.[58]

Tamsulosin and silodosin are selective α1 receptor blockers that preferentially bind to the α1A receptor in the prostate instead of the α1B receptor in the blood vessels. Less-selective α1 receptor blockers such as terazosin and doxazosin may lower blood pressure. The older, less selective α1-adrenergic blocker prazosin is not a first-line choice for either high blood pressure or prostatic hyperplasia; it is a choice for patients who present with both problems at the same time. The older, broadly non-selective alpha-blocker medications such as phenoxybenzamine are not recommended for control of BPH.[74] Non-selective alpha-blockers such as terazosin and doxazosin may also require slow dose adjustments as they can lower blood pressure and cause syncope (fainting) if the response to the medication is too strong.

5α-reductase inhibitors

The 5α-reductase inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors (PDE)

A 2018 Cochrane review of studies on men over 60 with moderate to severe

Several phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors are also effective but may require multiple doses daily to maintain adequate urine flow.[91][92] Tadalafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, was considered then rejected by NICE in the UK for the treatment of symptoms associated with BPH.[93] In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved tadalafil to treat the signs and symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia, and for the treatment of BPH and erectile dysfunction (ED), when the conditions occur simultaneously.[94]

Others

Self-catheterization

Intermittent urinary catheterization is used to relieve the bladder in people with urinary retention. Self-catheterization is an option in BPH when it is difficult or impossible to empty the bladder.[97] Urinary tract infection is the most common complication of intermittent catheterization.[98] Several techniques and types of catheter are available, including sterile (single-use) and clean (multiple use) catheters, but, based on current information, none is superior to others in reducing the incidence of urinary tract infection.[99]

Surgery

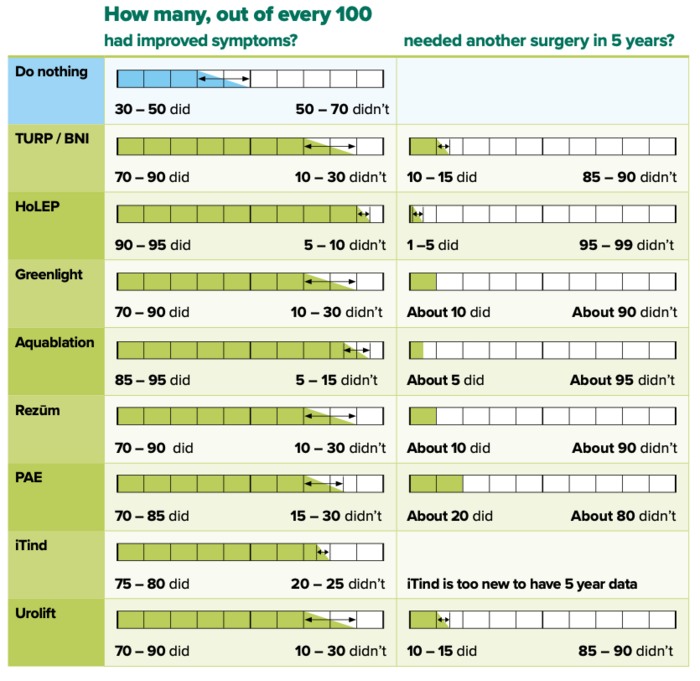

If medical treatment is not effective, surgery may be performed. Surgical techniques used include the following:

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP): the gold standard.[100] TURP is thought to be the most effective approach for improving urinary symptoms and urinary flow, however, this surgical procedure may be associated with complications in up to 20% of men.[100] Surgery carries some risk of complications, such as retrograde ejaculation (most commonly), erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, urethral strictures.[101]

- Transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP): rarely performed; the technique is similar to TURP but less definitive.

- Open prostatectomy: not usually performed nowadays due to its high morbidity, even if the results are excellent.

Other less invasive surgical approaches (requiring spinal anesthesia) include:

- Holmium laser ablation of the prostate (HoLAP)

- Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLeP)

- Thulium laser transurethral vaporesection of the prostate (ThuVARP)

- Photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP)

- Aquablation therapy: a type of surgery using a water jet to remove prostatic tissue.

Minimally invasive procedures

Some less invasive procedures are available according to patients' preferences and co-morbidities. These are performed as

- Prostatic artery embolization: an endovascular procedure performed in interventional radiology.[102] Through catheters, embolic agents are released in the main branches of the prostatic artery, in order to induce a decrease in the size of the prostate gland, thus reducing the urinary symptoms.[103]

- Water vapor thermal therapy (marketed as Rezum): This is a newer office procedure for removing prostate tissue using steam aimed at preserving sexual function.

- Prostatic urethral lift (marketed as UroLift): This intervention consists of a system of a device and an implant designed to pull the prostatic lobe away from the urethra.[104]

- Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT) is an outpatient procedure that is less invasive compared to surgery and involves using microwaves (heat) to shrink prostate tissue that is enlarged.[100]

- Temporary implantable nitinol device (TIND and iTIND): is a device that is placed in the urethra that, when released, is expanded, reshaping the urethra and the bladder neck.[105]

Alternative medicine

While

Epidemiology

Globally, benign prostatic hyperplasia affects about 94 million males as of 2019[update].[3]

The prostate gets larger in most men as they get older. For a symptom-free man of 46 years, the risk of developing BPH over the next 30 years is 45%. Incidence rates increase from 3 cases per 1000 man-years at age 45–49 years, to 38 cases per 1000 man-years by the age of 75–79 years. While the prevalence rate is 2.7% for men aged 45–49, it increases to 24% by the age of 80 years.[169]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Prostate Enlargement (Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia)". NIDDK. September 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ PMID 26331999.

- ^ PMID 36273485.

- PMID 30953341.

- PMID 10796740.

- PMID 11869585.

- PMID 11276294.

- PMID 22792684.

- PMID 6206240.

- PMID 7685427.

- ^ a b c d e f g "NHS England » Decision support tool: making a decision about enlarged prostate (BPE)". www.england.nhs.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management, NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)

- ^ "Urge incontinence". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- PMID 21250138.

- PMID 18459613.

- PMID 22808960.

- ^ "Urination – difficulty with flow". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Urination – painful". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Bladder outlet obstruction". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- PMID 18499191.

- PMID 1924456.

- ^ "Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions". NCBI Bookshelf. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Proscar (finasteride) Prescribing Information" (PDF). FDA – Drug Documents. Merck and Company. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- S2CID 3257666.

- S2CID 205020623.

- PMID 9394847.

- ^ S2CID 24288565.

- PMID 16882745.

- PMID 18308097.

- ^ S2CID 204734045.

- S2CID 251657694.

- S2CID 251658492.

- PMID 18492814.

- PMID 12646998.

- PMID 18500180.

- S2CID 205442245.

- PMID 11916745.

- PMID 12680332.

- PMID 9594331.

- S2CID 32639108.

- PMID 11916755.

- S2CID 22937831.

- .

- arXiv:1503.01376 [cs.DM].

- PMID 16985902.

- ^ PMID 17030221.

- ^ S2CID 220652018.

- PMID 21475707.

- PMID 24139351.

- S2CID 58586667.

- S2CID 74205747.

- PMID 31340802.

- PMID 26587887.

- PMID 33485763.

- PMID 20199941.

- S2CID 10731245.

- ^ PMID 30306544.

- PMID 30953341.

- ^ "Benign prostatic hyperplasia". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017.

- PMID 30953341.

- ^ De Jong Y, Pinckaers JH, Ten Brinck RM, Lycklama à Nijeholt AA. "Influence of voiding posture on urodynamic parameters in men: a literature review" (PDF). Nederlands Tijdschrift voor urologie. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- PMID 25051345.

- S2CID 40954757.

- S2CID 21001077.

- PMID 16551208.

- PMID 16846678.

- PMID 16230138.

- PMID 11744466.

- S2CID 6640867.

- ^ PMID 12535426.

- ^ S2CID 73366414.

- S2CID 24428368.

- PMID 12853821.

- (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2016.

- PMID 14767299.

- S2CID 38243275.

- ^ PMID 19002123.

- PMID 16406915.

- PMID 14499682.

- PMID 1383816.

- PMID 24708055.

- ^ Deters L. "Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy Treatment & Management". Medscape. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ PMID 14681504.

- ^ PMID 19825505.

- ^ PMID 17105794.

- PMID 16526818.

- PMID 25605342.

- ^ "Evidence | Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 23 May 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- PMID 30480763.

- S2CID 23929021.

- PMID 30480763.

- ^ "Hyperplasia (benign prostatic) – tadalafil (terminated appraisal) (TA273)". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "FDA approves Cialis to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- PMID 17105794.

- S2CID 30983780.

- ^ "Prostate enlargement (benign prostatic hyperplasia)". Harvard Health Content. Harvard Health Publications. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- PMID 12235537.

- PMID 34699062.

- ^ PMID 34180047.

- ^ "Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) - Risks". nhs.uk. 24 October 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- S2CID 12154537.

- PMID 27019980.

- PMID 27274321.

- S2CID 5712711.

- PMID 27862831.

- PMID 33373708.

- ^ PMID 30552937.

- ISSN 0022-5347.

- PMID 22857762.

- ^ PMID 30283994.

- ^ PMID 25937539.

- ^ PMID 26614889.

- PMID 28861405.

- ISSN 0022-5347.

- ^ PMID 36042295.

- ^ PMID 35778579.

- PMID 23370938.

- PMID 26506952.

- ^ PMID 33373708.

- ^ PMID 20052586.

- PMID 33933503.

- PMID 20605316.

- ^ PMID 26283011.

- PMID 33837819.

- PMID 28044238.

- PMID 29102672.

- PMID 29603912.

- ISSN 0022-5347.

- ^ PMID 27476128.

- PMID 23357348.

- ISSN 2051-4158.

- PMID 25698433.

- PMID 33933503.

- ^ PMID 29645352.

- ^ PMID 23370938.

- PMID 35843995.

- ^ "Evidence | Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 23 May 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- PMID 31487977.

- PMID 33104947.

- PMID 33796882.

- PMID 15311026.

- PMID 21658839.

- PMID 31621175.

- PMID 20092844.

- PMID 32633020.

- PMID 21802121.

- PMID 29593470.

- PMID 33837819.

- PMID 24331152.

- PMID 27862831.

- PMID 24475799.

- PMID 26216644.

- ISSN 0022-5347.

- PMID 31831295.

- PMID 26506952.

- PMID 32065861.

- PMID 29694702.

- ISSN 1931-7220.

- PMID 25382816.

- PMID 36070450.

- PMID 32124019.

- ^ "NHS England » Decision support tool: making a decision about enlarged prostate (BPE)". www.england.nhs.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- S2CID 25609876.

- S2CID 13815057.

- PMID 18423748.

- PMID 37345871.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- PMID 12361895.